Unveiling Potosí: A Legacy of Silver and Splendor

Nestled high in the Bolivian Andes, Potosí is a living museum of colonial history, where the immense wealth and historical significance that the discovery of Cerro Rico and silver mining bestowed upon the region. Now a UNESCO site, the city has become a unique and culturally rich destination.

Unveiling Potosí: A Legacy of Silver and Splendor

Nestled high in the Bolivian Andes at an elevation of 4,090 meters (13,420 feet), the city of Potosí is a living testament to the immense wealth and historical significance that silver mining bestowed upon the region. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site, Potosí has earned its place as a unique and culturally rich destination, where the echoes of colonial history resonate through its streets and landmarks.

Potosí's history is intricately tied to the discovery of the Cerro Rico (Rich Hill) silver deposit in 1545, transforming the city into one of the largest and wealthiest urban centers in the Americas during the Spanish colonial period. The extraction of silver from the Cerro Rico mines fueled the Spanish Empire's economic power, making the city a vital hub of colonial trade and commerce.

Cerro Rico: The Mountain of Silver

Before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors, the region around Potosí was inhabited by indigenous peoples, including the Quechua and Aymara. These communities had established settlements in the high-altitude Andean region, living off agriculture and trade. The transformation of Potosí began in 1545 when the Spaniards, led by Diego Huallpa, discovered Cerro Rico, a mountain brimming with silver. This event marked the onset of significant changes for the city and the entire Spanish Empire. The allure of wealth drew settlers, adventurers, and fortune seekers from Spain and beyond.

The subsequent silver boom turned Potosí into one of the wealthiest and most populated cities in the Americas during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Cerro Rico mines became a vital source of silver for the Spanish Crown, funding its imperial ambitions. The city's prosperity attracted migrants, merchants, and laborers, creating a diverse and bustling urban center.

Colonial Grandeur: Architecture, Institutions, and Cultural Legacy

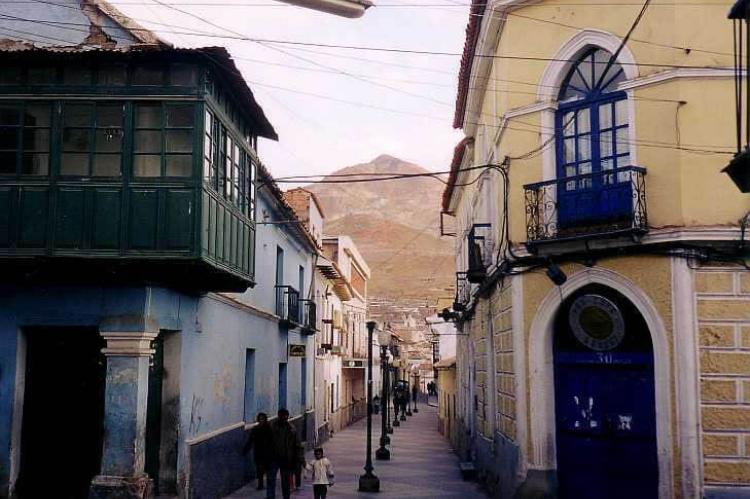

The influx of wealth from the Cerro Rico mines not only transformed Potosí into one of the wealthiest cities in the Americas but also gave birth to a vibrant architectural landscape that continues to captivate visitors today. The cityscape is adorned with a stunning array of colonial buildings, each bearing witness to Potosí's historical grandeur and cultural heritage.

Baroque and Mannerist Splendor

Potosí's architectural legacy is characterized by the Baroque and Mannerist styles that flourished during the colonial period. Churches, mansions, and public buildings are embellished with intricate facades, elaborate ornamentation, and sculptural details, reflecting the city's prosperity and the influence of Spanish colonial aesthetics.

The Cathedral of Potosí stands as the crowning jewel of the city's architectural heritage. This imposing structure, constructed between 1564 and 1600, exemplifies Spanish Baroque architecture with its ornate facade, soaring towers, and lavish interior adorned with gold leaf and precious metals. The cathedral's significance extends beyond its architectural grandeur; it serves as a spiritual and cultural focal point for the local community, hosting religious ceremonies, festivals, and artistic events celebrating Potosí's rich cultural heritage.

Mining and Money: The Casa de la Moneda

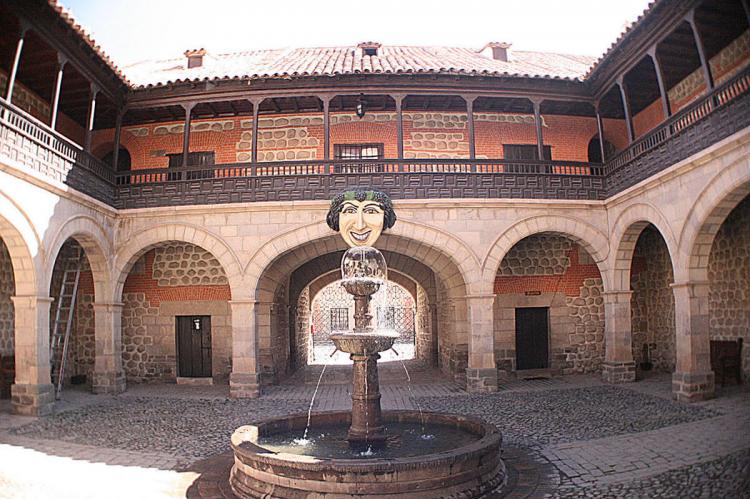

Another iconic landmark that speaks to Potosí's colonial legacy is the Casa de la Moneda, or the Royal Mint. This structure, established in 1572, played a pivotal role in the economic machinery of the Spanish Empire. Here, silver extracted from the Cerro Rico mines was minted into coins, fueling the empire's economic expansion and global trade networks.

The Casa de la Moneda is a testament to Potosí's economic significance and a repository of its cultural and historical heritage. Today, the building has been transformed into a museum, offering visitors a fascinating glimpse into the city's mining history, colonial economy, and artistic achievements. Exhibits showcase minting techniques, colonial-era currency, and artworks highlighting Potosí's enduring legacy as a center of wealth, commerce, and cultural exchange.

The Human Cost: Labor, Exploitation and Resilience

The economic prosperity of Potosí during the colonial era was built on the backs of indigenous and African slave laborers who endured unimaginable hardships within the mines of Cerro Rico. Their stories reveal the profound human cost of extracting silver from the earth's bowels and underscore the complexities of colonial power dynamics and economic exploitation.

Indigenous communities, including the Quechua and Aymara peoples, were among the first to inhabit the region surrounding Potosí. With the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century and the discovery of the Cerro Rico silver deposit, their lives were irrevocably changed. Forced into labor by the encomienda system, indigenous individuals were compelled to work in the mines under grueling conditions, facing the constant threat of injury, illness, and death.

The exploitation of indigenous labor was further exacerbated by the introduction of the Mita system, a form of mandatory labor imposed by Spanish colonial authorities. Under the Mita, indigenous communities were required to provide a quota of workers for the mines on a rotational basis. This system, while ostensibly structured, often resulted in the forced recruitment of individuals, separating families and communities and subjecting them to harsh and dehumanizing treatment.

In addition to indigenous labor, the Spanish also relied heavily on enslaved Africans to meet the growing demand for labor in the mines of Potosí. Enslaved Africans, captured and transported across the Atlantic through the transatlantic slave trade, faced unspeakable cruelty and brutality as they were forced to work in the treacherous conditions of the mines. Many perished due to exhaustion, disease, and accidents, and their lives were sacrificed in the pursuit of silver wealth.

The human toll of mining in Potosí was staggering. Indigenous and African laborers faced the constant threat of cave-ins, toxic gases, and mining-related accidents. They endured backbreaking labor in cramped and poorly ventilated tunnels, often without adequate protective gear or medical care. Countless lives were lost in the pursuit of silver, their sacrifices overshadowed by the quest for colonial wealth and power.

Despite the immense challenges and suffering they endured, indigenous and enslaved individuals demonstrated remarkable resilience and resistance. Through acts of defiance, solidarity, and cultural preservation, they sought to assert their humanity and dignity in the face of exploitation and oppression. Their stories serve as a testament to the enduring spirit of resistance and resilience that continues to shape Potosí's cultural identity today.

Decline and Legacy: From Prosperity to Challenges

The decline of Potosí's economic prominence marked a pivotal chapter in the city's history, signaling a shift from unparalleled prosperity to enduring challenges that would shape its trajectory for centuries to come. Various internal and external factors converged to precipitate this decline, leaving an indelible legacy on the city and its inhabitants.

Depletion of Silver Deposits

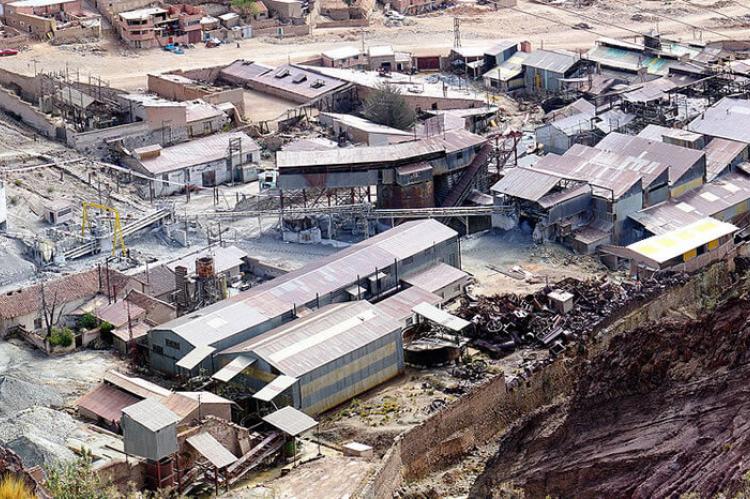

At the heart of Potosí's economic decline lay the depletion of the once-abundant silver deposits that had fueled the city's prosperity for generations. As the Cerro Rico mines were progressively exhausted, extracting silver became increasingly costly and labor-intensive, diminishing the profitability of mining operations. Despite efforts to explore deeper veins and implement new extraction techniques, the diminishing returns ultimately undermined Potosí's economic viability.

Financial Mismanagement and Economic Challenges

In addition to resource depletion, Potosí grappled with issues of financial mismanagement and economic instability that exacerbated its decline. The Spanish Crown's imposition of high taxes and monopolistic control over mining operations stifled innovation and discouraged investment in alternative industries, exacerbating the city's dependence on silver exports. Furthermore, fluctuations in global markets, currency devaluations, and geopolitical conflicts further eroded Potosí's economic resilience, leaving it vulnerable to external shocks and crises.

Geopolitical Shifts and Changing Dynamics

Broader geopolitical shifts and changing dynamics within the Spanish Empire also influenced the decline of Potosí. As colonial territories elsewhere in the Americas gained prominence and strategic importance, Potosí's centrality waned, diminishing its significance as a vital hub of colonial trade and commerce. Furthermore, the rise of competing colonial powers, such as Britain and Portugal, challenged Spain's hegemony and disrupted established trade networks, further marginalizing Potosí's economic prospects.

Legacy and Enduring Challenges

Despite its economic decline, Potosí's legacy as a symbol of colonial wealth and exploitation endures, shaping its identity and trajectory in the modern era. The city's rich historical heritage, characterized by its architectural splendor and cultural significance, continues to attract visitors and scholars worldwide, providing insights into the complexities of colonialism and its legacies.

However, Potosí also grapples with enduring challenges stemming from its legacy of extractive industries, economic dependency, and social inequality. Environmental degradation, health hazards associated with mining activities, and socio-economic disparities underscore the need for sustainable development strategies and community empowerment initiatives to address the city's contemporary challenges and foster inclusive growth.

UNESCO World Heritage Site: Preserving Potosí's Legacy

In 1987, UNESCO recognized the historical and cultural importance of Potosí by designating it as a World Heritage site. The city's inclusion on this prestigious list acknowledges its outstanding universal value and the need to preserve its unique architectural and cultural legacy.

Potosí's cityscape is characterized by a stunning array of colonial architecture reflecting its past's grandeur. The historic center is a treasure trove of well-preserved churches, mansions, and public buildings from the colonial era. At the heart of Potosí lies Plaza 10 de Noviembre, a central square surrounded by historic buildings, including the Cathedral and the Municipal Palace. The plaza is a bustling center where locals and visitors converge, providing a vivid snapshot of daily life in the city against a backdrop of architectural splendor.

The Cathedral of Potosí, built between 1564 and 1600, is a prime example of Spanish Baroque architecture, with its ornate facade and impressive interior. The Casa de la Moneda, or the Royal Mint, is one of the city's most iconic landmarks. This grand tower, built in the 18th century, served as the colonial mint, where the extracted silver was minted into coins. The Casa de la Moneda is a testament to the economic importance of Potosí during this period and now houses a museum that showcases the city's mining history and colonial art.

Cerro Rico looms over the city, symbolizes its prosperity, and is a stark reminder of the human costs associated with the mining industry. Over centuries, the extraction of silver from these mines led to immense wealth for the Spanish Crown but came at the expense of the lives and labor of indigenous and enslaved Africans. Today, tours of the Cerro Rico mines give visitors a glimpse into miners' challenging and dangerous conditions.

Conclusion: Reflecting on Potosí's Legacy

In reflection, Potosí, Bolivia, emerges as a profound testament to the intersections of wealth, power, and exploitation that defined the colonial era in the Americas. The legacy of the Cerro Rico mines reverberates through the city's streets, bearing witness to the immense fortunes amassed and the profound human costs incurred in the pursuit of silver.

The UNESCO World Heritage designation bestowed upon Potosí underscores its universal significance, urging global appreciation and preservation of its cultural and architectural heritage. As visitors traverse its historic cobblestone streets and marvel at its Baroque cathedrals and colonial mansions, they are confronted with the enduring legacy of a city that once stood as the silver heart of the Andes.

Yet, amidst its historical grandeur, Potosí grapples with contemporary challenges, including environmental degradation, socio-economic disparities, and the legacy of extractive industries. The city's future hinges on its ability to navigate these complexities, embracing sustainable development practices and fostering inclusive growth that honors its past while building a resilient future.