The Peninsular Ranges System: A Geological and Ecological Marvel of Northwestern Mexico

The Peninsular Ranges System is a coastal mountain range forming the backbone of Mexico's Baja California Peninsula. It stretches from the Southern California border to the peninsula's southern tip and features diverse ecosystems, geological formations, and endemic species.

The Peninsular Ranges System: A Geological and Ecological Marvel of Northwestern Mexico

Running parallel to the Pacific Ocean, the Peninsular Ranges System is a remarkable series of coastal mountain ranges that form the backbone of the Baja California Peninsula in northwestern Mexico. This rugged geological feature spans approximately 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) from the international border with Southern California to the peninsula's southern tip, showcasing diverse ecosystems, geological formations, and endemic species.

Geographic Extent and Composition

The Peninsular Ranges System comprises six distinct mountain ranges dominated by Mesozoic granitic rocks. These ranges extend from elevations of approximately 150 meters (500 feet) to 3,300 meters (10,800 feet) above sea level, encompassing a mosaic of desert, xeric shrubland, and temperate coniferous pine-oak forest ecoregions.

NASA topographic map of Baja California.

Notable Mountain Ranges

Sierra de Juárez

The northernmost range of the Peninsular Ranges System and of Mexico, the Sierra de Juárez, rises sharply from the eastern Sonoran Desert, reaching its highest peak at 1,980 meters (6,500 feet) above sea level. The lower western slopes are part of the California coastal sage and chaparral sub-ecoregion, while the eastern slopes transition into the arid Sonoran Desert ecoregion, characterized by its unique desert flora.

The higher elevations of the Sierra de Juárez and those of the Sierra San Pedro Mártir to the south form part of the Sierra Juarez and San Pedro Martir pine-oak forests ecoregion. This unique ecosystem is a "Sky Island," an elevated temperate forest surrounded by lower, more arid lands. Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) is a common shrub in the understory of these coniferous forests.

Sierra de San Pedro Mártir

Acting as a drainage divide between waters flowing west into the Pacific Ocean and east into the Gulf of California, the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir is home to Picacho del Diablo ('Devil's Peak'), the highest point in the Baja California Peninsula at 3,096 meters (10,157 feet) above sea level. This granitic mountain range is characterized by young, rocky soils that are poorly developed, shallow, and low in organic matter.

The Sierra de San Pedro Mártir National Park is located within this range. It is known for its pine trees, including the towering Pinus lambertiana, which can reach up to 70 meters (230 feet), and its unique granite rock formations. Additionally, the National Astronomical Observatory is located in the range at an elevation of 2,830 meters (9,280 feet) above sea level, taking advantage of the clear skies and favorable atmospheric conditions.

The coniferous forests of the Sierra de San Pedro and Sierra de Juárez Mártir comprise a "Sky Island," an elevated temperate forest surrounded by lower, more arid lands. Dominant species include the Parry pinyon (Pinus quadrifolia), Jeffrey Pine (Pinus jeffreyi), lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), white fir (Abies concolor), and incense cedar (Libocedrus decurrens). The herbaceous stratum is formed by Bromus species and big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), while epiphytes and fungi are abundant throughout the forests.

Sierra de San Borja

The Sierra de San Borja, also known as Sierra La Libertad, is located south of the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir and is the northernmost outpost of the "Great Mural" rock art in the central Baja California mountains. With its highest point at Cerro La Sandia (1,775 meters or 5,823 feet above sea level), this nearly uninhabited range is characterized by desert vegetation and lacks the oak-pine forests found in the higher and more humid mountain ranges to the north and south.

The Sierra de San Borja is the northernmost outpost of the "Great Mural" rock art, which consists of prehistoric paintings of humans and other animals, often larger than life-size, on the walls and ceilings of natural rock shelters. Tourists visit the San Francisco Borja Mission, founded in 1762, and the extensive prehistoric rock art scattered throughout the mountains.

Sierra de San Francisco

Situated north of San Ignacio, the Sierra de San Francisco is the northernmost of a series of volcanic ranges running the length of eastern Baja California Sur. Its rugged terrain, drained by steep canyons harboring mesquite forests and palm groves, forms the eastern edge of the Vizcaíno Desert and links the southern peninsula's tropical components with the temperate influences of the north.

The Sierra de San Francisco vegetation is characteristic of the Baja California Desert ecoregion. The mountain range, along with the Tres Vírgenes volcanic complex and Sierra Guadalupe, forms the eastern edge of the Vizcaíno Desert and facilitates the transition between the tropical and temperate elements of the peninsula's flora and fauna.

The prehistoric rock art pictographs of the Cochimí people, known as the Rock Paintings of Sierra de San Francisco, are found within these mountains and are a UNESCO World Heritage site. The El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve encompasses the Sierra de San Francisco, protecting its unique natural and cultural heritage.

Sierra de la Giganta

Rising abruptly from the Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez), the Sierra de la Giganta runs parallel to the southeastern coast of the Baja California Peninsula in Baja California Sur state. The highest point in the range is Cerro de la Giganta, which is 1,176 meters (3,858 feet) above sea level and near the city of Loreto. The range is riddled with canyons and caves, including the Tabor Canyon, a natural landmark known for its natural swimming pools and steep walls suitable for climbing and abseiling.

The Sierra de la Giganta is predominantly dry (xeric) shrubland, with the Baja California Desert ecoregion covering the range's Pacific (western) slope and the Gulf of California xeric scrub ecoregion covering the Gulf (eastern) slope. However, valley streams with year-round water sustain palm oases, with groves of the native Washingtonia robusta and other moisture-loving plants.

The caves within the Sierra de la Giganta were once inhabited by the Guaycura, the region's first settlers. Their heritage is preserved in the numerous petroglyphs and cave paintings throughout the range.

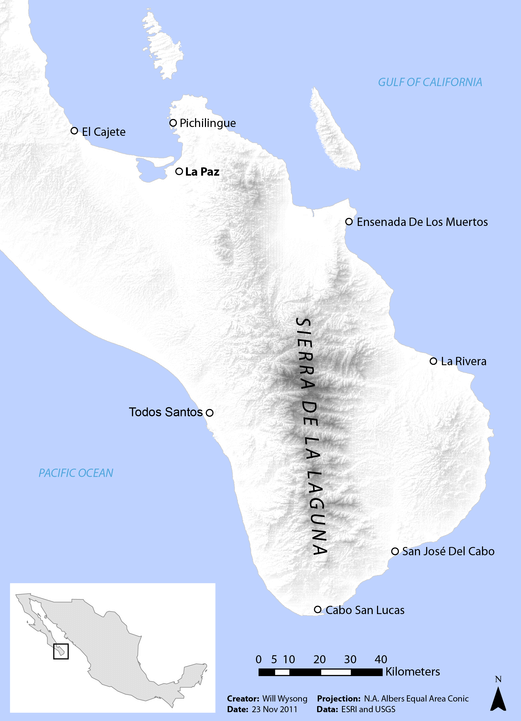

Sierra de la Laguna

The southernmost range of the Peninsular Ranges System, the Sierra de la Laguna, is located at the southern end of the Baja California Peninsula. In prehistoric times, this range was an island, resulting in a distinctive flora and fauna with many endemic species and subspecies, including a local subspecies of Mexican Pinyon (Pinus cembroides subsp. lagunae) that dominates the higher elevations.

The vegetation in the Sierra de la Laguna is stratified by elevation, with the dry San Lucan xeric scrub ecoregion extending from sea level to 250 meters (820 feet), followed by the Sierra de la Laguna dry forests ecoregion from 250 to 800 meters (820 to 2,620 feet). Above 800 meters (2,600 feet) above sea level, the dry forests transition into the Sierra de la Laguna pine-oak forests, exploited commercially for timber. Cattle raising is also common in the oak woodland and dry forest zones.

The Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve was designated in 2003 to protect these temperate woodlands, dry forests, and xeric shrublands, constituting the most critical reproduction site for the primary hummingbird species of Mexico and Latin America. Unfortunately, the area of the Biosphere Reserve also represents the least explored territory in Baja California Sur.

Map showing the Sierra de la Laguna Mountain Range.

Tres Vírgenes Volcanic Complex

Located about 36 kilometers (22 miles) northwest of the town of Santa Rosalía in northeastern Baja California Sur, the Tres Vírgenes volcanic complex contains the only large stratovolcanoes on the Baja California Peninsula. This volcanic ridge, which extends towards the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California, is composed of three volcanoes aligned northeast to southwest:

1. El Viejo: The oldest volcano, made up of three lava domes.

2. El Azufre: The next oldest, with a central dome and pyroclastic fans.

3. El Vírgen (or La Vírgen): The youngest and most conspicuous, comprising at least six cones.

The Tres Vírgenes volcanic complex is part of a more extensive geological system that has shaped the diverse landscapes and ecosystems of the Baja California Peninsula over millions of years. The volcanic activity and associated processes have contributed to the formation of the rugged mountain ranges, unique rock formations, and varied soil types that characterize the region, influencing the distribution and diversity of flora and fauna found within the Peninsular Ranges System.

Conclusion

The Peninsular Ranges System, stretching the entirety of the Baja California Peninsula, is a remarkable geological and ecological marvel that showcases the incredible diversity and complexity of northwestern Mexico's natural heritage. From the towering coniferous forests of the Sierra de Juárez and San Pedro Mártir in the north to the unique volcanic landscapes of the Sierra de San Francisco and Tres Vírgenes complex, this mountain backbone has played a pivotal role in shaping the peninsula's intricate mosaic of ecosystems.

Each mountain range's varied topography, climatic conditions, and geological histories have given rise to a rich plant and animal life tapestry, including numerous endemic species found nowhere else on Earth. The presence of ancient rock art and archaeological sites within these ranges further underscores the deep connection between the region's natural landscapes and rich cultural heritage.

As conservation efforts continue to protect and preserve the unique ecosystems of the Peninsular Ranges System, these mountains stand as a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life in the face of the harsh desert environments surrounding them. They serve as a reminder of the importance of safeguarding these ecological treasures for their intrinsic value and the invaluable insights they offer into the intricate web of life that has evolved over millennia in this remarkable corner of the world.

The Peninsular Ranges System and its associated volcanic complexes represent a living laboratory for scientific exploration. They offer opportunities to unravel the mysteries of geological processes, study the dynamics of ecological interactions, and gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that drive biodiversity and endemism in isolated and fragmented landscapes.

As continued exploration and appreciation of the wonders of the Peninsular Ranges System take place, observers are reminded of nature's profound beauty and resilience of nature, and the urgent need to protect and conserve these unique and irreplaceable natural wonders for future generations.