The Tropical Andes: Earth's Most Biodiverse Hotspot

Stretching from western Venezuela to northern Bolivia, the Tropical Andes is a remarkable mountain system that includes snow-capped peaks, cloud forests, grasslands, and river valleys within a continuous region. It is recognized as a Biodiversity Hotspot—and the most biologically diverse on the planet.

Crown of Biodiversity: The Tropical Andes and Its Ecological Legacy

Stretching from western Venezuela to northern Bolivia, the Tropical Andes is one of the most remarkable places on Earth. Covering more than 1,500,000 square kilometres (580,000 square miles), this vast mountain system encompasses snow-capped peaks, verdant cloud forests, high-altitude grasslands, and plunging river valleys — all within a single continuous region. It is formally recognized as a Biodiversity Hotspot — and not merely one among many. By virtually every measure, the Tropical Andes ranks as the most biologically diverse hotspot on the planet.

Home to approximately one-sixth of all plant species on Earth, despite occupying less than 1% of the world's land area, the Tropical Andes defies easy description. Its staggering richness is the product of elevation, climate, geological history, and sheer geographic complexity — conditions that have shaped an extraordinary mosaic of habitats and driven the evolution of countless species found nowhere else.

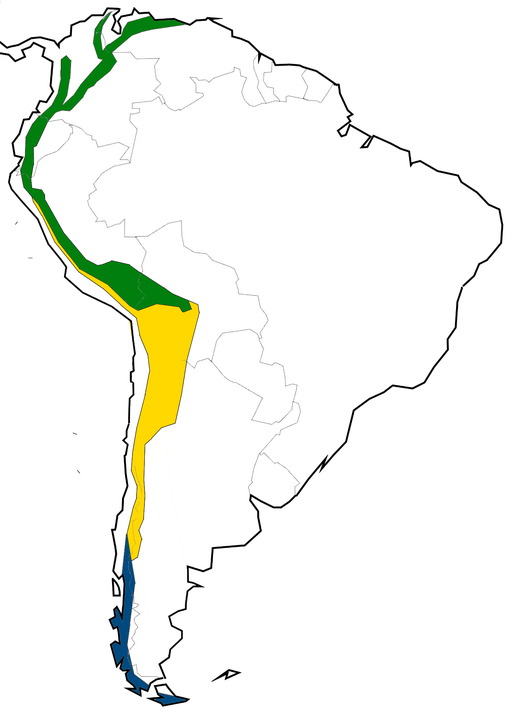

Map depicting the climatic regions of the Andes: Tropical Andes in green, Dry Andes in yellow, and Wet Andes in blue.

A Region of Remarkable Scope

The Tropical Andes encompasses the northernmost ranges of the Andes Mountains system, which is divided into three broad climate zones: the Tropical Andes, the Dry Andes, and the Wet Andes. The Tropical Andes includes the Venezuelan Andes, the Colombian Andes, the Ecuadorian Andes, most of the Peruvian Andes, and much of the Bolivian Andes — five distinct national expressions of a single interconnected mountain chain.

The terrain varies enormously across the region. Tropical rainforests cloak the lower slopes between roughly 500 and 1,500 metres (1,600 to 4,900 feet) above sea level. Cloud forests — among the most biologically productive ecosystems on Earth — occupy a middle band from about 800 to 3,500 metres (2,600 to 11,500 feet). Above them, open grasslands and shrublands known as páramo and puna stretch toward the permanent snowline at 3,000 to 4,800 metres (9,800 to 15,700 feet). Dry forests and xeric shrublands occupy rain-shadow valleys in between.

Within this landscape lie some of South America's most iconic geographical features. Colca Canyon in Peru, at 3,223 metres (10,574 feet) deep, is among the deepest gorges on Earth. Lake Titicaca, straddling the Peruvian-Bolivian border at 3,810 metres (12,500 feet) above sea level, is the world's highest commercially navigable lake.

Map depicting the Tropical Andes Region.

Biomes and Ecological Zones

Four major biomes converge within the Tropical Andes, giving it an ecological complexity unmatched by any other hotspot. Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests dominate the wetter slopes, while tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests occupy the more arid interior valleys. Deserts and xeric shrublands appear where mountains block moisture-laden winds, and montane grasslands and shrublands — the páramo and puna ecosystems — define the high-altitude landscapes above the treeline.

These broad biomes break down further into more than twenty distinct ecoregions — defined areas where natural communities share similar environmental conditions and species assemblages. Among the most significant is the Northern Andean Páramo of Colombia and Ecuador, a high-altitude ecosystem of sponge-like grasses and cushion plants that acts as a critical freshwater reservoir for millions of people downstream. Equally important are the Eastern Cordillera Real Montane Forests, extraordinarily species-rich cloud forests running along the eastern flank of the Andes through Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Further south, the Peruvian Yungas form a transition zone between Andean highlands and Amazonian lowlands, renowned for exceptional bird diversity, while the Bolivian Yungas perform a similar role on Bolivia's eastern slopes, sheltering rare and endemic plant communities. Rounding out the picture, the Central Andean Wet Puna and the Bolivian Montane Dry Forests illustrate the region's wide range of moisture regimes and altitudinal variation — two ecosystems that could hardly be more different, yet both shaped by the same underlying mountain geography.

Map depicting the Ecoregions of the Tropical Andes.

Biodiversity Without Equal

The numbers describing the Tropical Andes' biodiversity are, frankly, difficult to absorb. The region hosts approximately 30,000 vascular plant species — around one-sixth of all plant life on Earth — compressed into a fraction of a percent of the planet's land surface. The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund estimates that 50% or more of these species are endemic, meaning they exist nowhere else. The Tropical Andes leads the world in plant endemism.

Animal life is equally remarkable. The region supports around 980 amphibian species, of which more than 670 are endemic, making it the most diverse on Earth for this class of vertebrates. Among birds, the hotspot harbors over 1,700 species, a third of them found nowhere else, surpassing all other global hotspots in avian diversity. Mammals are well represented, too, with a substantial number of endemic species adapted to life at extreme altitudes and in specialized habitats.

Freshwater fish add another dimension to this picture. More than 375 documented species inhabit the rivers and lakes of the Tropical Andes. However, the conservation status of many remains poorly understood — a gap that itself represents an urgent scientific challenge.

Threats to an Irreplaceable Heritage

The same geographic qualities that make the Tropical Andes so rich — its accessibility, its fertile soils, its mineral deposits, its rivers — also make it a target for development pressures that have already drastically reduced its original extent. Conservation scientists estimate that the hotspot has lost the majority of its original vegetation cover, with much of what remains fragmented and under continuing threat.

Deforestation and Land Use Change

Expanding agricultural frontiers pose the most pervasive and immediate danger. Forests are cleared for cattle ranching, soybean cultivation, coca production, and smallholder farming at rates that continue to accelerate in many parts of the region. Habitat fragmentation — the division of intact forest into isolated patches — is particularly damaging for species with low dispersal ability, interrupting wildlife corridors and creating islands of habitat too small to sustain viable populations. Illegal logging compounds these pressures, degrading forest ecosystems even where outright clearing has not occurred.

Mining and Resource Extraction

The Tropical Andes hosts some of the world's richest mineral deposits. Large-scale and artisanal mining operations for gold, copper, silver, and coal have left extensive environmental scars across the region. Gold mining is of particular concern: the use of mercury to extract ore contaminates rivers and soils with a toxin that bioaccumulates through aquatic food chains, posing serious health risks to both wildlife and the human communities who depend on these waterways. Oil and gas extraction in the montane regions of Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia has added roads, pipelines, and spills to the region's burden.

Urbanization and Infrastructure

Rapid population growth and urbanization in Andean cities — Medellín, Quito, Cusco, La Paz, and many smaller centers — have expanded urban footprints into surrounding natural habitats. Road-building, in particular, drives deforestation by opening previously inaccessible areas to settlement and extraction. Industrial development contributes to air, water, and soil pollution that degrades habitats well beyond immediate construction zones.

Climate Change

Climate change presents a threat of a different character — diffuse, difficult to reverse, and interacting with all the others. Rising temperatures are shifting species' ranges upward in altitude, effectively compressing habitats as warmth-tolerant species encroach from below while cool-adapted species retreat from the mountains above them. The páramo — a globally unique high-altitude ecosystem — is especially vulnerable to warming and drying trends.

Glacial retreat is accelerating across the Tropical Andes, with consequences that extend far beyond biodiversity. Andean glaciers serve as critical water storage systems, releasing meltwater during dry seasons to feed rivers and support agriculture and human consumption for tens of millions of people. Their loss will alter hydrological cycles, threatening both freshwater ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

Conservation: What Is Being Done

Despite the scale of these pressures, conservation in the Tropical Andes is not a story of failure alone. Governments, non-governmental organizations, research institutions, local communities, and Indigenous peoples are engaged in a complex and ongoing effort to slow habitat loss, restore degraded ecosystems, and build sustainable alternatives to destructive land-use practices.

Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories

A network of national parks, biological reserves, and protected areas spans the Tropical Andes, providing legal protection for critical habitats and serving as refuges for threatened species. These areas vary widely in size, resources, and effectiveness, but collectively they represent an essential foundation for biodiversity conservation. Indigenous territories often overlap with or adjoin protected areas, and indigenous-led stewardship — drawing on deep ecological knowledge accumulated over centuries — has proven to be among the most effective means of maintaining ecosystem integrity.

Sustainable Land Management

Agroforestry systems that integrate trees, crops, and livestock have shown promise as alternatives to wholesale forest clearing. These approaches can maintain biodiversity, protect soil fertility, and provide economic returns for farmers — addressing the underlying economic pressures that drive deforestation. Reforestation programs, particularly those using native species, are restoring degraded lands in several countries, though the scale of restoration needed far exceeds current capacity.

Community Engagement and Local Stewardship

Conservation outcomes improve markedly when local communities are genuine partners rather than passive subjects of externally imposed policies. Community-based monitoring, co-management of protected areas, and support for traditional ecological practices have all demonstrated positive results across the Tropical Andes. Empowering communities to benefit economically from intact ecosystems — through ecotourism, payment for ecosystem services, and sustainable harvesting — creates incentives that align human livelihoods with conservation goals.

Looking Ahead

The Tropical Andes represent something genuinely irreplaceable. Its concentration of life — tens of thousands of plant species, nearly a thousand amphibians, more bird species than any other hotspot, freshwater systems connecting the Andes to the Amazon — exists nowhere else on Earth and cannot be recreated if lost. The services this region provides are equally irreplaceable: water for cities and farms, carbon stored in montane forests, climate regulation, and the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples who have shaped these landscapes for millennia.

Protecting the Tropical Andes demands sustained investment, genuine political commitment from the governments of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and international support commensurate with the region's global significance. It also requires listening carefully to the people who live within it — the farmers, Indigenous communities, scientists, and conservationists who understand its rhythms most intimately. The window for effective action is open, but it will not remain so indefinitely.