The Peru-Chile Trench: South America's Deepest Frontier and the Bolivian Orocline

The Peru-Chile Trench represents the deepest oceanic depression in the South Pacific and serves as the active collision zone where the Nazca Plate slides beneath the South American continent. This submarine canyon is intertwined with the dramatic coastal bend known as the Bolivian Orocline.

The Bolivian Orocline and Peru-Chile Trench: Partners in Planetary Deformation

Along South America's western coast, beneath the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the Humboldt Current, lies one of Earth's most spectacular geological features. The Peru-Chile Trench, also known as the Atacama Trench, represents the deepest oceanic depression in the South Pacific and serves as the active collision zone where the Nazca Plate slides beneath the South American continent. This submarine canyon, intertwined with the dramatic coastal bend known as the Bolivian Orocline, tells a story of planetary-scale forces that have sculpted the Andes Mountains and continue to shape one of the world's most geologically active regions.

An Oceanic Abyss of Continental Scale

Extending along the eastern Pacific Ocean like a massive submarine scar, the Peru-Chile Trench stretches approximately 5,900 kilometers (3,666 miles) from the Ecuador-Peru border to the Chile Triple Junction near Tierra del Fuego. This immense geological feature maintains an average width of 64 kilometers (40 miles) while encompassing a total area of 590,000 square kilometers (227,800 square miles), making it larger than the entire country of France.

The trench reaches its maximum depth at Richards Deep, located at coordinates 23°10′45″S 71°18′41″W, where the ocean floor plunges to 8,065 meters (26,460 feet) below sea level. This profound depth places the Peru-Chile Trench among the world's deepest oceanic features, exceeded only by trenches in the western Pacific such as the Mariana and Tonga trenches. To comprehend this depth, imagine stacking more than 29 Empire State Buildings on top of each other and submerging the entire structure beneath the ocean surface.

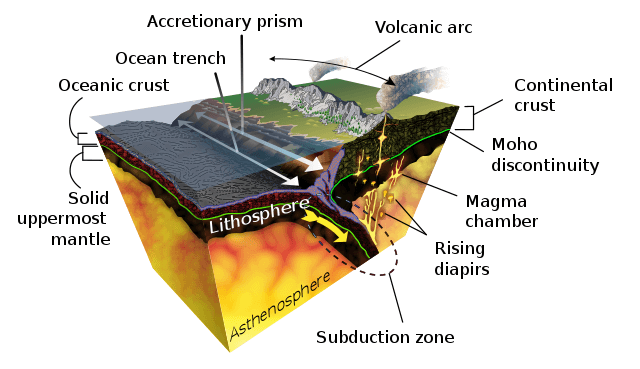

Diagram of the geological process of subduction.

The Mechanics of Continental Collision

The Peru-Chile Trench represents the surface expression of one of Earth's most active subduction zones, where the oceanic Nazca Plate descends beneath the continental South American Plate at rates varying from 2 to 10 centimeters (0.8 to 3.9 inches) per year. This seemingly gradual process generates enormous forces capable of raising mountain ranges and triggering some of the planet's most powerful earthquakes.

The subducting Nazca Plate, formed at the East Pacific Rise and Chile Rise spreading centers, carries oceanic crust that ranges in age from relatively young near the ridges to over 40 million years old where it enters the trench. As this dense oceanic crust descends into Earth's mantle, it undergoes metamorphosis under extreme pressure and temperature conditions, releasing water and other volatiles that play crucial roles in generating the magma that feeds the Andes' volcanic arc.

The geometric complexity of this subduction system varies dramatically along the trench's length, influenced by factors including the age and thickness of the descending plate, the presence of bathymetric features like seamounts and ridges, and changes in convergence angle and rate. These variations create distinct segments along the trench, each characterized by unique patterns of seismic activity, volcanic expression, and crustal deformation.

The Bolivian Orocline: A Continental Bend in Time and Space

One of the most striking features associated with the Peru-Chile Trench system is the Bolivian Orocline, a dramatic bend in both the Andes Mountains and the adjacent oceanic trench that occurs around 18°S latitude in southern Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile. This geological phenomenon represents one of the most pronounced examples of oroclinal bending on Earth, where an originally linear mountain chain has been curved into a distinctive arc shape.

The Bolivian Orocline divides the Andes into distinct northern and southern segments, each with characteristic orientations, structural patterns, and geological histories. North of the orocline, the mountain chain trends northwest-southeast, while south of the bend, it assumes a north-south orientation. This dramatic change in direction reflects complex interactions between the subducting Nazca Plate, the overriding South American Plate, and the broader patterns of continental drift and plate reorganization that have occurred over millions of years.

Research suggests that the formation of the Bolivian Orocline involved a combination of factors, including changes in the relative motion between the Nazca and South American plates, the collision and accretion of exotic terranes, and the influence of pre-existing continental structures. The timing of oroclinal bending remains a subject of scientific debate, with evidence suggesting that the process may have occurred primarily during the Cenozoic Era, coinciding with the major phases of Andean mountain building.

Sedimentary Archives and Turbidity Currents

The Peru-Chile Trench serves as a massive sediment trap, collecting material eroded from the Andes Mountains and transported by rivers, wind, and ocean currents. However, the sedimentary fill varies dramatically along the trench's length, reflecting differences in continental drainage patterns, climate conditions, and oceanographic processes.

The northern portion of the trench, adjacent to Peru's coastal rivers, contains substantial accumulations of land-derived sediments that create relatively flat trench floors. Turbidity currents, underwater avalanches triggered by earthquakes or sediment instability, periodically sweep down the continental slope, carrying enormous volumes of sediment into the trench axis. These underwater flows can travel hundreds of kilometers at speeds exceeding 50 kilometers per hour (31 miles per hour), carving submarine canyons and depositing thick layers of graded sediments.

In contrast, the central portion of the trench, adjacent to Chile's hyperarid Atacama Desert, receives minimal terrestrial sediment input due to the region's extremely low precipitation and limited surface water flow. This sediment-starved environment exposes the trench's fundamental tectonic architecture, allowing researchers to observe directly the structural relationships between the descending oceanic plate and the overlying continental margin.

Topographic map of the Andes. The Bolivian Orocline is visible as a bend in the coastline and the Andes in the lower half of the map.

Seismic Powerhouse and Natural Hazards

The Peru-Chile Trench ranks among the world's most seismically active regions, generating earthquakes that have profoundly impacted South American societies throughout recorded history. The subduction interface, where the Nazca and South American plates maintain frictional contact, periodically releases accumulated stress through ruptures that can extend for hundreds of kilometers along the plate boundary.

The 1960 Chilean earthquake, centered near Valdivia, represents the most powerful earthquake ever recorded, reaching magnitude 9.5 and generating tsunamis that caused damage across the Pacific Basin. The 2010 Maule earthquake (magnitude 8.8) and the 2014 Iquique earthquake (magnitude 8.2) demonstrate the ongoing seismic activity associated with the trench system, each causing significant casualties and economic losses while advancing scientific understanding of megathrust earthquake processes.

Beyond the immediate impacts of ground shaking, earthquakes along the Peru-Chile Trench pose significant tsunami risks to Pacific-facing coastlines. The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan highlighted the far-reaching consequences of submarine earthquakes, leading to improved tsunami early warning systems and coastal preparedness measures throughout the Pacific region.

Deep-Sea Ecosystems and Extremophiles

Despite the crushing pressures, perpetual darkness, and frigid temperatures characterizing the Peru-Chile Trench, this extreme environment supports remarkable biological communities that have evolved unique adaptations to deep-sea conditions. The hadal zone, representing depths exceeding 6,000 meters (19,685 feet), harbors organisms found nowhere else on Earth, many of which remain scientifically undescribed.

Recent expeditions using advanced deep-sea vehicles have documented diverse communities of amphipods, xenophyophores (giant single-celled organisms), and specialized bacteria that thrive in the trench environment. These organisms have developed extraordinary adaptations to withstand pressures exceeding 800 times atmospheric pressure, including modified cellular structures, specialized enzymes, and unique metabolic pathways.

Cold seeps along the trench axis support chemosynthetic ecosystems where bacteria derive energy from chemical reactions involving methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other reduced compounds. These primary producers support complex food webs, including polychaete worms, bivalve mollusks, and various crustacean species. The study of these extreme environments provides insights into the limits of life on Earth and the potential habitability of similar environments on other planets.

The Humboldt Current Connection

The Peru-Chile Trench's influence extends far beyond its role as a tectonic boundary, fundamentally shaping the oceanographic conditions that support one of the world's most productive marine ecosystems. The trench's proximity to the coast creates upwelling conditions where deep, nutrient-rich waters rise to the surface, fueling the Humboldt Current ecosystem that supports massive populations of anchovies (Engraulis ringens), sardines (Sardinops sagax), and other commercially important species.

This upwelling system creates a biological paradox where some of Earth's most productive marine waters overlie one of its deepest oceanic trenches. The contrast between the teeming surface waters and the sparsely populated deep-sea environment illustrates the dramatic vertical zonation that characterizes marine ecosystems and the profound influence of physical oceanographic processes on biological productivity.

Scientific Frontiers and Technological Advances

Modern investigation of the Peru-Chile Trench employs cutting-edge technologies that push the boundaries of deep-sea exploration. Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) equipped with high-resolution cameras, sampling equipment, and scientific instruments can operate at depths previously accessible only to the most sophisticated crewed submersibles. These platforms allow researchers to conduct systematic surveys of trench environments, collect biological specimens, and monitor real-time changes in seafloor conditions.

Seismic networks both on land and on the seafloor continuously monitor the trench system, providing early warning for tsunamis while advancing understanding of subduction zone processes. Ocean bottom seismometers deployed directly above the descending Nazca Plate record microearthquakes and other subtle signals that reveal details about plate interface conditions, fluid flow patterns, and stress accumulation processes.

International research collaborations continue investigating fundamental questions about subduction dynamics, earthquake generation, and the deep carbon cycle. The Peru-Chile Trench serves as a natural laboratory where theories about convergent margin processes can be tested through direct observation, experimentation, and long-term monitoring. As scientific capabilities advance and new technologies become available, this remarkable geological feature will undoubtedly continue revealing secrets about Earth's interior dynamics and the processes that shape our planet's surface.

The Peru-Chile Trench and its associated Bolivian Orocline represent more than geological curiosities; they embody the dynamic processes that have shaped South American geography, influenced regional climate patterns, and created the conditions supporting diverse ecosystems both above and below the ocean surface. Understanding these features provides crucial insights into natural hazards, resource distribution, and the fundamental mechanisms driving planetary-scale geological processes.