South America: Continent of Extremes

From snow-capped peaks to steaming rainforests, deserts, and wetlands, South America is a diverse continent spanning from Caribbean shores to Tierra del Fuego. With nearly 440 million people, it hosts societies shaped by Indigenous, European, African, and global influences.

The South American Continent: Fourth Largest, First in Biodiversity

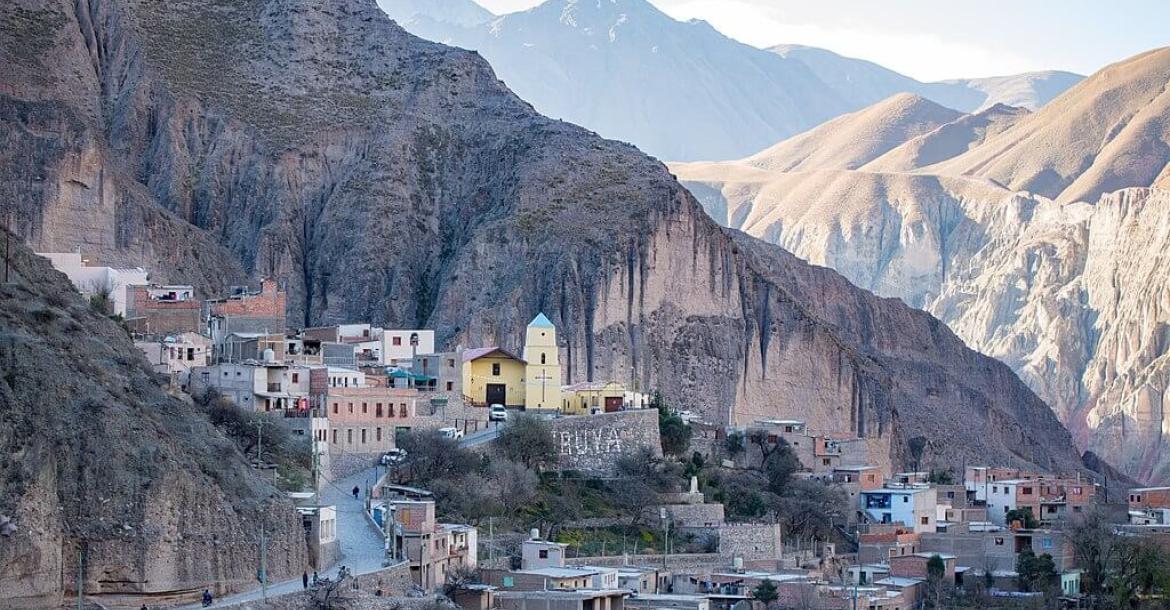

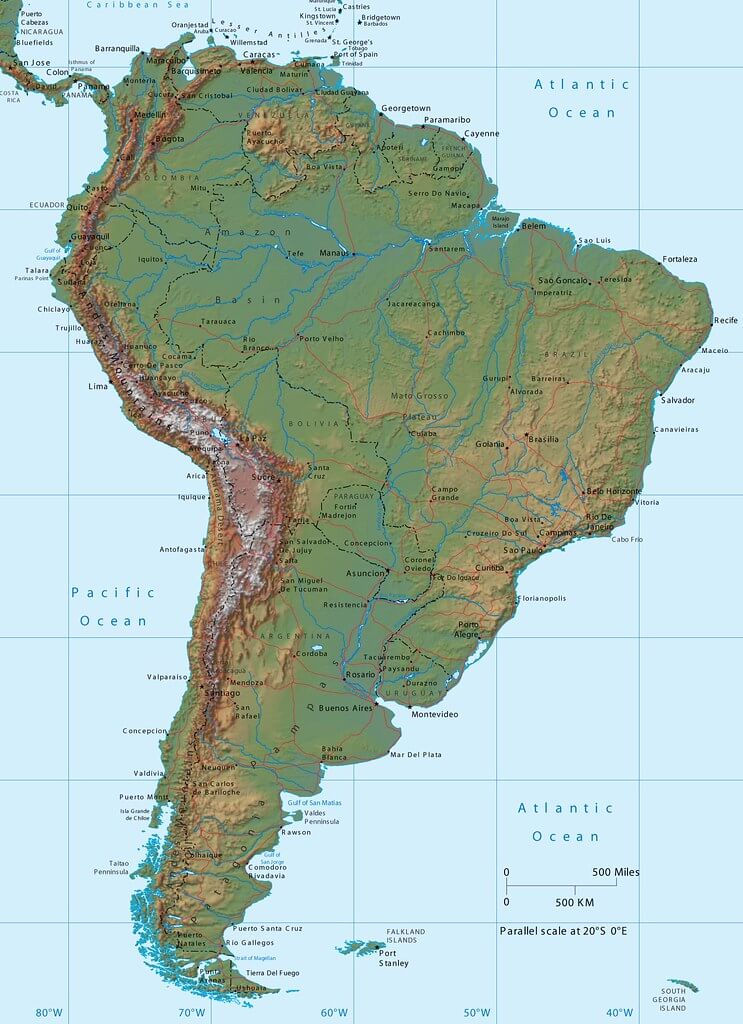

From the snow-capped peaks of the world's longest mountain range to the steaming vastness of Earth's greatest rainforest, from the driest desert on the planet to wetlands the size of France, South America defies easy characterization. This triangular landmass of approximately 17.84 million square kilometers (6.89 million square miles)—the world's fourth-largest continent—stretches 7,640 kilometers (4,750 miles) from the Caribbean shores of Colombia to the windswept channels of Tierra del Fuego, encompassing every climatic zone from equatorial jungle to sub-Antarctic tundra. Home to nearly 440 million people across 12 sovereign nations and 3 dependent territories, South America is a crucible where Indigenous civilizations, European colonization, the African diaspora, and waves of global migration have forged societies as diverse as the landscapes they inhabit. Here, the Amazon River discharges more water than the next seven largest rivers combined, jaguars hunt in forests that produce twenty percent of Earth's oxygen, and the Andes rise as a 7,000-kilometer (4,350-mile) granite spine that has shaped the continent's climate, cultures, and destiny for millions of years.

Physiographic map of South America.

Geological Origins: A Continent Adrift

South America's extraordinary geography reflects a dramatic geological history spanning hundreds of millions of years. The continent originated as part of Gondwana, the ancient southern supercontinent that also included Africa, Antarctica, Australia, India, and Arabia. Beginning approximately 180 million years ago during the Jurassic period, Gondwana began fragmenting as tectonic forces pulled the landmasses apart. South America remained connected to Africa until roughly 140 million years ago, when the South Atlantic Ocean started to open as the two continents drifted westward.

This westward movement continues today at approximately 2-4 centimeters (0.8-1.6 inches) annually as the South American Plate overrides the Nazca and Antarctic plates along the continent's Pacific margin. This collision created the Andes Mountains, the world's longest continental mountain range, extending over 7,000 kilometers (4,350 miles) from Venezuela through Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. The Andes' highest peak, Aconcagua in Argentina, reaches 6,962 meters (22,841 feet), making it the tallest mountain outside Asia.

The eastern portion of South America consists primarily of ancient crystalline shields—the Guiana Shield in the north and the Brazilian Shield in the center and south—composed of Precambrian rocks dating back more than 1.5 billion years. These stable platforms, among Earth's oldest geological formations, have been exposed and eroded for hundreds of millions of years, creating the relatively flat highlands and plateaus characteristic of interior Brazil, the Guianas, and parts of Venezuela.

Between these ancient shields and the young Andes lies the vast sedimentary basin of the Amazon, formed as the continent's interior gradually subsided and filled with sediments eroded from surrounding highlands. This basin, roughly 7 million square kilometers (2.7 million square miles), represents one of the world's largest river drainage systems and hosts the most biodiverse ecosystem on Earth.

Geography of Superlatives

South America's physical geography reads like a catalog of Earth's extremes. The Amazon Rainforest covers approximately 5.5 million square kilometers (2.1 million square miles), storing an estimated 150-200 billion tonnes of carbon and producing roughly 20% of the planet's oxygen. The Amazon River, fed by more than 1,100 tributaries, discharges an average of 209,000 cubic meters (7.4 million cubic feet) of water per second into the Atlantic Ocean—approximately 20% of all freshwater entering the world's oceans.

The Atacama Desert in northern Chile holds the distinction of being Earth's driest non-polar desert. Some weather stations in the Atacama have never recorded measurable rainfall, and the average annual precipitation across much of the desert is less than 15 millimeters (0.6 inches). This extreme aridity results from the rain shadow of the Andes combined with the cold Humboldt Current offshore, which creates a temperature inversion that prevents cloud formation.

The Pantanal, spanning portions of Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay, comprises the world's largest tropical wetland at approximately 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 square miles)—roughly the size of England. During the wet season from November through March, floodwaters inundate as much as 80% of the Pantanal, creating a vast aquatic ecosystem supporting extraordinary concentrations of wildlife, including caimans, capybaras, giant otters, and over 650 bird species.

The continent's river systems rank among the world's mightiest. Beyond the Amazon, the Paraná-Paraguay system drains much of south-central South America, flowing 4,880 kilometers (3,030 miles) before emptying into the Río de la Plata estuary between Argentina and Uruguay. The Orinoco River, draining northern South America through Venezuela and Colombia, creates a vast inland delta with labyrinthine channels through dense tropical forests.

Climate: Equator to Antarctica

South America's north-south extension of more than 7,600 kilometers (4,720 miles) creates remarkable climatic diversity. The equator crosses through Ecuador, Colombia, and northern Brazil, while the continent extends south beyond 55°S latitude—nearly to Antarctica. This latitudinal range, combined with the Andes' dramatic elevation changes, produces virtually every climate classification on Earth.

The Amazon Basin experiences a tropical rainforest climate with minimal seasonal temperature variation and abundant year-round rainfall, typically 2,000-3,000 millimeters (79-118 inches) annually. High humidity and temperatures averaging 25-28°C (77-82°F) create ideal conditions for the dense vegetation that characterizes the world's largest rainforest.

The Cerrado of central Brazil experiences a tropical savanna climate with distinct wet (October-April) and dry (May-September) seasons. These seasonal precipitation patterns shape vegetation communities adapted to periodic drought and fire, creating grasslands dotted with drought-resistant trees and shrubs.

The Pampas of Argentina and Uruguay feature a humid subtropical to temperate climate with warm summers and cool winters. This fertile grassland region receives 500-1,200 millimeters (20-47 inches) of rainfall annually, supporting the cattle ranching and grain production that have made Argentina a major agricultural exporter.

Patagonia, stretching across southern Argentina and Chile, experiences progressively colder and windier conditions as it moves southward. The Andes create a dramatic rain shadow, with Chilean Patagonia receiving abundant precipitation from Pacific storms while Argentine Patagonia east of the mountains remains semi-arid. Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost archipelago, experiences a cold oceanic climate with strong winds, cool summers, and winters that, while relatively mild for the latitude, bring snow and freezing temperatures.

The Andean highlands exhibit complex mountain climates, primarily determined by elevation. The páramo ecosystem between 3,000 and 4,800 meters (9,800 and 15,700 feet) features cold temperatures, high levels of ultraviolet radiation, frequent frost, and unique plant adaptations. Higher still, permanent snow and glaciers cap the tallest peaks, though climate change has caused dramatic glacier retreat throughout the Andes over recent decades.

Biodiversity: A Living Treasury

South America harbors extraordinary biological diversity, hosting an estimated 40% of Earth's plant and animal species despite representing only 12% of global land area. This exceptional richness reflects the continent's climatic diversity, complex topography, and relatively recent geological separation from other landmasses, which allowed unique evolutionary pathways.

The Amazon alone contains approximately 390 billion individual trees representing an estimated 16,000 species, more tree diversity than all of North America. The rainforest supports perhaps 10% of all species on Earth, including 2.5 million insect species, 40,000 plant species, 3,000 freshwater fish species, 1,300 bird species, and 430 mammal species. New species continue to be discovered regularly—scientists estimate that thousands of Amazonian species remain unknown to science.

The Atlantic Forest of eastern Brazil, though reduced to approximately 12% of its original extent, remains a biodiversity hotspot with exceptional levels of endemism. Approximately 40% of its plant species and 30% of its animal species exist nowhere else on Earth. The forest once covered 1.5 million square kilometers (580,000 square miles) but has been largely cleared for agriculture, leaving fragmented remnants that desperately require conservation.

The Andean region supports remarkable biodiversity across dramatic elevation gradients. Cloud forests on eastern Andean slopes contain extraordinary concentrations of endemic species, particularly orchids, bromeliads, and birds. The high-altitude páramo ecosystem, though seemingly barren, hosts uniquely adapted plants such as the iconic frailejón (Espeletia) and provides crucial water regulation services to millions of people in Andean cities.

The Galápagos Islands, lying 900 kilometers (560 miles) off Ecuador's coast, serve as a natural laboratory for evolution. The archipelago's isolation and varied environments fostered unique endemic species, including giant tortoises, marine iguanas, flightless cormorants, and Darwin's finches—species whose variations helped inspire Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection.

Indigenous Heritage and Colonial Transformation

Archaeological evidence suggests humans first reached South America at least 14,500 years ago, with the Monte Verde site in southern Chile providing compelling evidence of early human occupation. These first Americans likely crossed from Asia via the Bering land bridge during the last Ice Age, then migrated southward through the Americas over thousands of years.

By the time of European contact, South America supported diverse Indigenous societies ranging from nomadic hunter-gatherers in Patagonia and the Amazon to sophisticated agricultural civilizations in the Andes. The Inca Empire, centered in Cusco, Peru, represented the largest pre-Columbian state in the Americas, ruling approximately 10 million people across a territory stretching 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) from southern Colombia to central Chile. The Incas built remarkable stone cities like Machu Picchu, engineered extensive road networks traversing some of Earth's most difficult terrain, and developed agricultural systems that sustained dense populations in challenging Andean environments.

Spanish and Portuguese colonization, beginning with Columbus's Caribbean landings in 1492 and accelerating after 1500, devastated Indigenous populations through disease, forced labor, and warfare. Epidemics of smallpox, measles, and other Old World diseases to which Indigenous peoples had no immunity killed an estimated 90% of South America's pre-Columbian population within a century of contact. The Spanish conquered the Inca Empire in the 1530s, establishing colonial control over most of South America, except for the Portuguese-claimed territory that would become Brazil.

The colonial period transformed South America's demographic and cultural landscape through the forced migration of enslaved Africans and voluntary European immigration. Between 1500 and 1870, an estimated 4-5 million enslaved Africans were transported to South America, primarily to Brazil, where they worked on sugar, coffee, and gold mining operations. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, waves of European immigrants—particularly Italians, Spaniards, Germans, and Portuguese—settled in Argentina, Uruguay, southern Brazil, and Chile, fundamentally reshaping those societies.

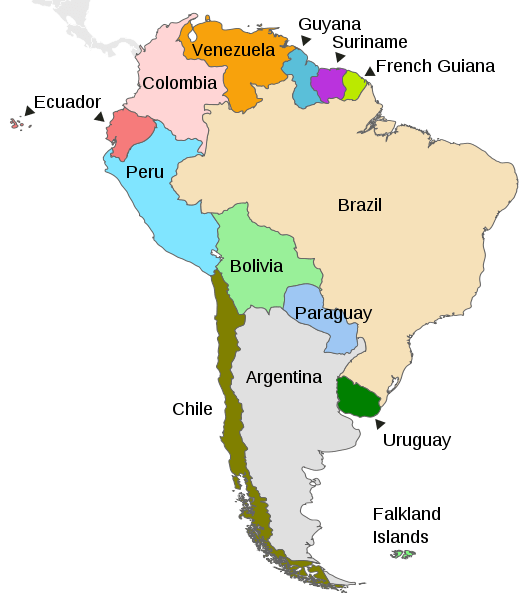

Map depicting the countries on the continent of South America.

Contemporary South America: Nations and People

Today, South America comprises twelve independent nations: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, and Venezuela, plus the dependent territories of French Guiana (France) and the Falkland Islands (United Kingdom). The continent's population of approximately 440 million (2026 estimate) ranks fifth globally after Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America, representing about 5.3% of humanity.

Brazil dominates demographically and geographically, containing nearly half the continent's population (approximately 215 million) and land area. Portuguese-speaking Brazil's size and population dwarf its Spanish-speaking neighbors, creating a unique linguistic and cultural divide within South America. The next most populous countries—Colombia (53 million), Argentina (46 million), Peru (35 million), and Venezuela (29 million)—together account for another 37% of the continental population.

Approximately 88% of South Americans live in urban areas, one of the highest urbanization rates of any continent. Megacities dominate: São Paulo (22 million metropolitan area), Buenos Aires (15 million), Rio de Janeiro (13 million), Lima (11 million), and Bogotá (11 million) rank among the world's largest urban agglomerations. This rapid urbanization, accelerating since the mid-20th century, has created both opportunities and challenges—economic dynamism alongside sprawling informal settlements, vibrant cultural scenes alongside urban poverty and crime.

The continent's population reflects its complex history of Indigenous societies, European colonization, African slavery, and later immigration from Asia and the Middle East. While mestizo (mixed European and Indigenous) populations predominate in most countries, significant variations exist across them. Argentina and Uruguay have predominantly European-descended populations due to massive late 19th- and early 20th-century immigration. Indigenous peoples remain the majority populations in Bolivia and significant minorities in Peru, Ecuador, and several other nations. Afro-descendant communities are particularly prominent in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador.

Cultural Tapestry

South America's cultural landscape reflects the fusion of Indigenous traditions, European (primarily Iberian) colonial heritage, African influences, and later Asian and Middle Eastern immigrant contributions. Spanish and Portuguese are the dominant languages, though hundreds of Indigenous languages survive, including Quechua (8-10 million speakers across Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador), Guaraní (official language of Paraguay alongside Spanish), and Aymara (centered in Bolivia and Peru).

The continent has profoundly influenced global culture. Brazilian samba and bossa nova, Argentine tango, Colombian cumbia, and numerous other musical traditions have achieved worldwide popularity. South American literature produced giants including Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda, and Isabel Allende, whose works helped define magical realism and contemporary Latin American letters. South American cuisine—from Argentine beef and Peruvian ceviche to Brazilian feijoada and Chilean wine—has gained international recognition.

Religious life reflects a blend of colonial Catholicism and Indigenous and African spiritual traditions, creating syncretic practices unique to South America. While Catholicism remains dominant, Protestant Evangelicalism has grown rapidly, and Afro-Brazilian religions like Candomblé maintain strong followings. Indigenous spiritual practices persist, often interwoven with Christian observances, reflecting centuries of cultural negotiation and resistance.

A Continent of Challenges and Promise

South America faces significant challenges in the 21st century. Economic inequality remains among the world's highest, with vast wealth concentrated alongside widespread poverty. Political instability has periodically disrupted several nations, while corruption undermines governance and development. Environmental pressures—particularly Amazon deforestation, glacier retreat, and coastal vulnerability to rising seas—threaten both ecosystems and human communities.

Yet the continent also demonstrates remarkable resilience, creativity, and potential. Democratic governance, though imperfect, has largely replaced the military dictatorships that plagued South America through much of the 20th century. Economic growth, while uneven, has created expanding middle classes. Environmental awareness is increasing, with Indigenous communities often leading conservation efforts. South America's extraordinary natural resources—from the Amazon's biodiversity to vast agricultural potential to mineral wealth—position it as crucial to humanity's future if managed sustainably.

From the Andes to the Amazon, from Caracas to Ushuaia, South America remains a continent of superlatives and contradictions, of ancient heritage and modern aspirations, where the thunder of Iguazú Falls echoes the complexity and grandeur of a land that continues to shape and be shaped by the currents of global history.