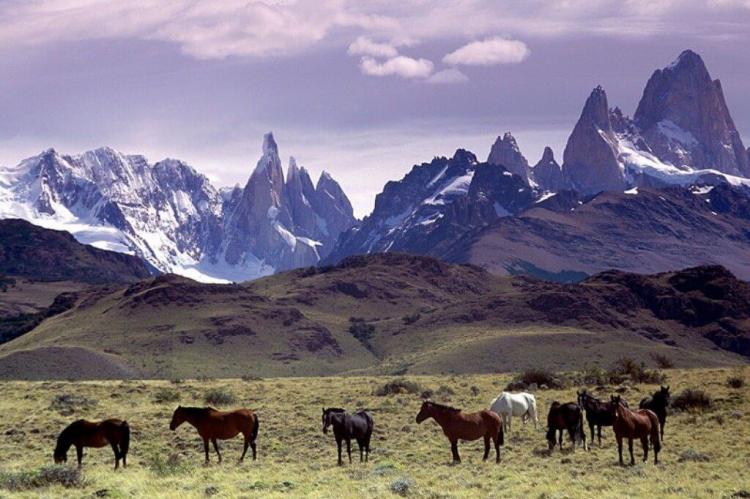

Patagonia: Nature's Last Frontier at the End of the World

Argentina and Chile share Patagonia, a vast and enigmatic region at the southern tip of South America. It is renowned for its stunning landscapes, rich biodiversity, and cultural heritage. This expansive region has a mix of arid plains, towering mountains, sprawling glaciers, and dense forests.

The Patagonian Wilderness: Conservation and Challenge in South America's Last Frontier

Shared between Argentina and Chile at the southern tip of South America, Patagonia stands as one of Earth's last great wilderness frontiers—a vast and enigmatic region renowned for stunning landscapes, rich biodiversity, and profound cultural heritage. Stretching from approximately 37°S latitude to the Drake Passage at 56°S, this expansive region encompasses nearly 1 million square kilometers (386,000 square miles) of dramatically diverse terrain, including arid steppes, towering mountains, sprawling glaciers, and dense temperate forests. Often described as one of the world's last remaining "Edens," Patagonia's landscapes captivate with their raw, untamed beauty: wind-sculpted plains where guanacos (Lama guanicoe) roam beneath endless skies, pristine fjords where tidewater glaciers calve icebergs into turquoise waters, and mountain ranges where condors (Vultur gryphus) soar above peaks piercing the Southern Hemisphere's dramatic skies. From the volcanic plateaus of northern Patagonia to the icy channels of Tierra del Fuego, this remarkable region represents a convergence of geographical extremes, ecological wonders, and human resilience that has captivated explorers, scientists, and adventurers for centuries while remaining one of the least densely populated areas on Earth.

Geographic Extent and Political Divisions

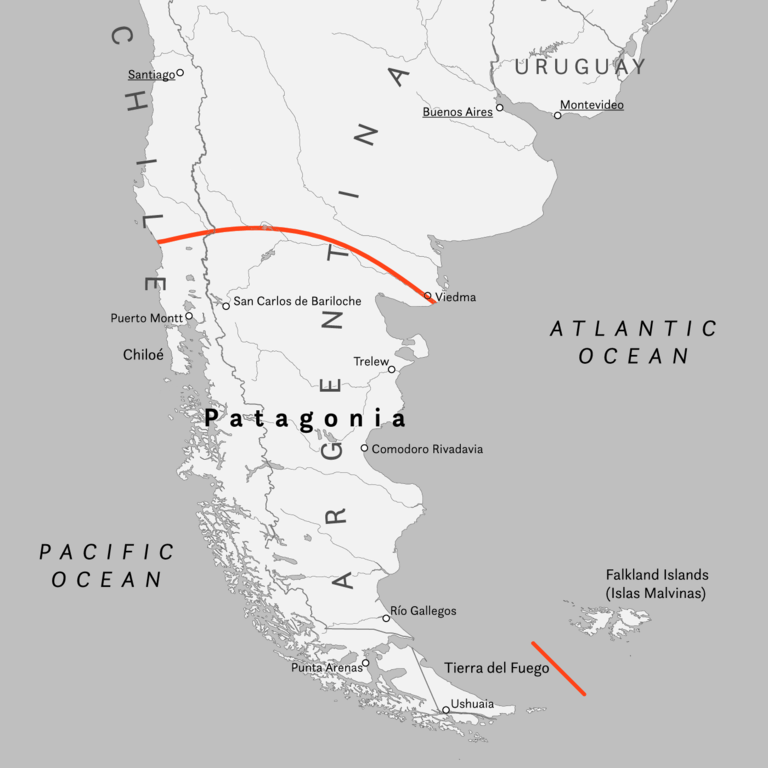

Patagonia encompasses substantial portions of southern Argentina and Chile, with boundaries that remain somewhat imprecise and subject to varying definitions. The northern limit is commonly considered to be the Colorado River in Argentina and the Bío Bío River in Chile, though some definitions extend Patagonia northward to include areas around 37°S. The southern terminus reaches Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn, where the continent meets the confluence of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans at the Drake Passage.

The Argentine Patagonia includes the provinces of Neuquén, Río Negro, Chubut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego, with the southern part of Buenos Aires Province sometimes included due to its geographical and climatic similarities. This eastern portion encompasses approximately 673,000 square kilometers (260,000 square miles) and is characterized primarily by semi-arid steppes and plains extending from the Andean foothills eastward to the Atlantic coast.

The Chilean Patagonia occupies the western slopes of the Andes. It extends to the Pacific coast, encompassing the entire Aysén and Magallanes administrative regions, with Palena Province in the Los Lagos Region also considered part of Chilean Patagonia. Some definitions extend northward to include the Chiloé Archipelago and parts of the Los Ríos and Araucanía regions. Chilean Patagonia covers approximately 240,000 square kilometers (92,700 square miles) and is characterized by extensive fjord systems, temperate rainforests, and the world's largest ice fields outside polar regions.

The international border roughly follows the Andean watershed divide. However, historical disputes and the region's complex geography have created some territorial ambiguities, which were resolved through various treaties and arbitrations over the 19th and 20th centuries.

Map of the Patagonia region in Argentina and Chile.

Topography and Major Landscapes

The southern Andes Mountains form Patagonia's dramatic spine, running north-south through the region and profoundly shaping the region's climate, ecology, and human settlement patterns. Unlike the towering peaks of the Central Andes further north, the Patagonian Andes are generally lower in elevation, typically ranging from 1,500 to 3,500 meters (4,900 to 11,500 feet). However, several peaks exceed 3,000 meters (9,800 feet).

The Andes divide Patagonia into distinct climatic and ecological zones. The western slopes receive abundant Pacific moisture, supporting lush temperate rainforests including the Valdivian and Magellanic forest types, extensive peatlands, and the Northern and Southern Patagonian Ice Fields. These ice fields, covering approximately 21,000 square kilometers (8,100 square miles) combined, represent the largest ice masses in the Southern Hemisphere outside Antarctica and feed dozens of major glaciers, including the famous Perito Moreno, Upsala, and Grey glaciers.

East of the Andes, the Patagonian Steppe dominates the landscape—a vast semi-arid shrubland and grassland ecosystem created by the rain shadow effect. This windswept plateau, characterized by coarse grasses, hardy shrubs, and volcanic outcrops, extends from the Andean foothills eastward hundreds of kilometers to the Atlantic coast. The steppe's seemingly monotonous appearance belies remarkable ecological diversity, with specialized plant and animal communities adapted to extreme winds, temperature variations, and limited precipitation.

The Atlantic coast features dramatic cliffs, extensive beaches, and important marine ecosystems. Peninsula Valdés in Argentine Patagonia represents one of the continent's most significant marine wildlife areas, hosting breeding colonies of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis), southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), southern sea lions (Otaria flavescens), and the world's largest breeding colony of Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus).

The Chilean Pacific coast creates one of Earth's most complex fjord and archipelago systems. Thousands of islands, countless channels, and deep fjords penetrate the continental margin, creating protected waterways that support unique marine ecosystems and provide critical habitat for marine mammals and seabirds.

Climate and Weather Patterns

Patagonia's climate varies dramatically due to its extensive latitudinal range and the profound influence of the Andes Mountains. The region experiences a temperate to cold climate overall, with significant east-west contrasts created by orographic effects.

Western Patagonia, exposed to moisture-laden Pacific air masses, receives abundant precipitation. Some areas of the Valdivian temperate rainforest receive average annual rainfall exceeding 4,000 millimeters (157 inches), creating jungle-like conditions. These wet western slopes support the lush forests and extensive ice fields that characterize Chilean Patagonia.

Eastern Patagonia experiences a cool, dry climate dominated by the rain shadow effect. Annual precipitation decreases dramatically east of the Andes, with much of the Patagonian Steppe receiving only 200-300 millimeters (8-12 inches) annually. The eastern plains endure persistent strong westerly winds—the famous Patagonian winds that have challenged explorers and settlers for centuries—capable of reaching sustained speeds exceeding 100 kilometers per hour (62 miles per hour).

Temperature patterns reflect both latitude and altitude. Coastal areas experience moderate temperatures moderated by ocean influences, while interior locations endure greater extremes. Summer (December-February) temperatures range from 15-25°C (59-77°F) in most areas, while winter (June-August) brings freezing temperatures and snow, particularly at higher elevations and southern latitudes.

Ecological Diversity and Biodiversity

Despite harsh environmental conditions, Patagonia supports remarkable biodiversity adapted to its extreme climates and varied habitats.

The Andean Patagonian Forest, Earth's southernmost forest ecosystem, extends along the western Andean slopes from approximately 37°S to 56°S. This unique temperate forest features species found nowhere else, including southern beeches (Nothofagus species) that dominate forest composition, the ancient alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides)—one of the world's longest-lived tree species with individuals exceeding 3,000 years—and the endemic monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides), a small marsupial more closely related to Australian marsupials than to other South American species, providing evidence of ancient Gondwanan connections.

The Patagonian Steppe, though often mischaracterized as barren, supports specialized wildlife including the guanaco, South America's wild camelid and the most characteristic large mammal of Patagonian plains, with populations exceeding 500,000 individuals; the endangered huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus) or South Andean deer, with fewer than 2,000 individuals remaining in fragmented populations along the Andean-steppe transition; Darwin's rhea (Rhea pennata), a flightless bird that once numbered in the millions but has declined significantly; and the Patagonian mara (Dolichotis patagonum), a large rodent resembling a hare that occupies open grasslands.

Predators include the puma (Puma concolor), apex predator throughout Patagonian ecosystems from forests to steppes; the culpeo or Andean fox (Lycalopex culpaeus), an adaptable canid occupying diverse habitats; and the Patagonian fox (Lycalopex griseus), smaller than the culpeo and more specialized for steppe environments.

Marine ecosystems support extraordinary diversity and abundance. The cold, nutrient-rich waters of the South Atlantic and Pacific support massive populations of fish, squid, and crustaceans that form the base of marine food webs. Peninsula Valdés hosts spectacular marine mammal aggregations, while Chilean fjords provide critical habitat for Chilean dolphins (Cephalorhynchus eutropia), marine otters (Lontra felina), and numerous seabird species.

Conservation and Recent Initiatives

Patagonia has emerged as a global conservation priority, with unprecedented initiatives transforming the regional landscape in recent years.

The Route of Parks (Ruta de los Parques) represents one of the world's most ambitious conservation corridors, spanning 2,800 kilometers (1,740 miles) through Chilean Patagonia from Puerto Montt to Cape Horn. This network links 17 national parks that protect approximately 11.8 million hectares (28 million acres)—one of the largest protected-area systems on Earth. The initiative emerged from the largest private land donation in history when Tompkins Conservation donated over 400,000 hectares (1 million acres) of former ranchlands, matched by Chilean government contributions of 3.6 million hectares (9 million acres) to create and expand parks.

In November 2025, Rewilding Chile and Tompkins Conservation donated 127,000 hectares (314,000 acres) to the Chilean government to establish Cape Froward National Park around the southernmost point of continental South America, with official designation expected within two years. This achievement marks the 16th park Tompkins Conservation has helped establish, continuing the legacy of Douglas and Kristine Tompkins in protecting Patagonian wilderness.

The National Huemul Corridor, established in 2024, aims to reconnect isolated huemul populations across Chilean Patagonia, enabling genetic exchange and habitat connectivity essential for the species' long-term survival. Conservationists discovered a new huemul subpopulation in 2025 at Cape Froward, demonstrating that remote areas still harbor undocumented wildlife populations.

Rewilding efforts have transformed degraded ranchlands into functioning ecosystems. Through removing livestock, dismantling fences, and restoring native vegetation, vast areas have rebounded, bringing back native wildlife and ecological processes. Species reintroductions have restored Darwin's rheas and other extirpated fauna to places where they had disappeared decades earlier.

In Argentina, conservation initiatives include expanding national parks, particularly in coastal areas to protect marine wildlife, and collaborative management involving government agencies, Indigenous communities, and conservation organizations to balance protection with sustainable use.

Cultural Heritage and Human History

Patagonia's human history spans millennia, beginning with Indigenous peoples who adapted remarkable strategies to survive in this challenging environment. The Tehuelche, Selk'nam (Ona), Yámana (Yaghan), Kawésqar (Alakaluf), and other groups developed distinct cultures suited to steppe, forest, and maritime environments, respectively. These populations suffered catastrophic declines following European contact through introduced diseases, violent conflicts, and cultural disruption, with some groups like the Selk'nam driven to near-extinction.

European exploration began in 1520 when Ferdinand Magellan navigated the strait that now bears his name. Subsequent expeditions by Drake, FitzRoy, Darwin, and others documented Patagonia's geography and natural history, though settlement remained limited due to harsh conditions and remoteness.

The 19th century brought significant colonization, including Welsh immigration to Chubut Province beginning in 1865. These settlers established agricultural communities that maintained Welsh language and culture while adapting to Patagonian conditions, creating unique cultural enclaves that persist in towns including Gaiman, Trelew, and Puerto Madryn.

Sheep ranching dominated the Patagonian economy by the early 20th century. The region's vast grasslands proved ideal for extensive grazing, with some estancias covering areas larger than small countries. At its peak, Patagonia supported over 20 million sheep, producing high-quality wool for international markets. This pastoral economy profoundly shaped regional culture, economy, and ecology, though overgrazing caused significant environmental degradation in some areas.

The Path Forward

Patagonia stands at a critical juncture where conservation success stories coexist with mounting environmental challenges. Climate change threatens glacial systems that regulate water resources and shape landscapes. Glacier retreat is accelerating across the region, with potential consequences for hydrology, ecosystems, and communities dependent on glacial meltwater.

Invasive species, particularly introduced herbivores like red deer and wild boar, compete with native fauna and alter ecosystem processes. In aquatic systems, introduced salmon and trout, while supporting recreational fisheries and aquaculture industries, impact native fish populations and marine ecosystems.

Economic pressures from resource extraction—including mining, oil and gas development, and industrial-scale fishing—create ongoing tensions between development and conservation. Sustainable tourism offers economic opportunities that incentivize protection, though poorly managed tourism can degrade the very wilderness that attracts visitors.

The unprecedented conservation achievements of recent years demonstrate that large-scale protection is achievable through collaboration among governments, non-governmental organizations, Indigenous communities, and private landowners. Whether these initiatives can maintain momentum and expand to address remaining conservation gaps will determine Patagonia's future as one of Earth's last great wilderness regions—a place where natural processes still dominate vast landscapes, where wildlife populations thrive in near-pristine ecosystems, and where the raw power and beauty of nature remain largely intact for future generations to experience and protect.