The Galápagos Archipelago: Conservation, Challenges, and Evolutionary Marvels

The Archipiélago de Colón, known as the Galápagos Islands, is an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean west of the coast of Ecuador, to which the islands belong. These islands are renowned for their unique biodiversity and pivotal role in developing Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection.

Biodiversity in Isolation: The Natural Wonders of the Galápagos Islands

The Archipiélago de Colón, more widely known as the Galápagos Islands, is an archipelago located in the Pacific Ocean approximately 965 kilometers (600 miles) west of the coast of Ecuador, the nation to which the islands belong. These islands are renowned for their unique biodiversity and pivotal role in developing the theory of evolution by natural selection, proposed by Charles Darwin following his visit aboard HMS Beagle in 1835. The islands, encompassing the Galápagos Province, the Galápagos National Park, and the Galápagos Marine Reserve, represent one of the planet's most important and unique ecological areas. Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1978, the islands' ecological, geological, and biological significance fascinates scientists and visitors alike.

Geographical and Geological Overview

The Galápagos Islands straddle the equator and are located in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, close to the Galápagos Triple Junction, where three tectonic plates converge—the Nazca Plate, the Cocos Plate, and the Pacific Plate. The entire archipelago has been formed due to volcanic activity caused by the Galápagos hotspot. This mantle plume heats the Earth's crust and leads to periodic volcanic eruptions. The Nazca Plate, on which the islands rest, is gradually moving eastward, subducting under the South American Plate at approximately 6.4 cm (2.5 in) per year.

The islands are geologically young, with some formed as recently as 8 million years ago. However, evidence suggests that volcanic activity in the region may date back up to 90 million years. Each island varies in age and degree of erosion, with the western islands, such as Fernandina and Isabela, being the youngest and still volcanically active. In contrast, the eastern islands, like Española and San Cristóbal, are significantly older and more eroded.

Climate and Ocean Currents

Although the Galápagos Islands sit on the equator, they experience a unique and varied climate influenced heavily by oceanic currents. The Humboldt Current, which flows north from the Antarctic, brings cool, nutrient-rich waters to the islands, making them cooler than expected for their latitude. This current, combined with the Cromwell Current (the Equatorial Undercurrent) and the Panama Current, contributes to the region's rich marine biodiversity.

The islands experience two primary seasons:

- Garúa season (June to November): Characterized by cooler temperatures (averaging around 22°C/72°F) and a steady drizzle or mist, known locally as garúa, that blankets the highlands. During this time, the Humboldt Current is strongest, cooling the waters and making nutrients plentiful.

- Warm season (December to May): The temperature rises (up to 25°C/77°F), and occasional heavy rainfall occurs, especially in the highlands. The seas become calmer and warmer, attracting a variety of marine species. This period is also marked by the potential for El Niño events, which can significantly disrupt local weather patterns and aquatic life by warming ocean waters and reducing nutrient levels.

Precipitation levels vary across the islands, with the highland regions of larger islands, such as Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal, receiving much more rainfall than the coastal regions. This results in distinct ecological zones, from lush forests to arid lowlands.

Biodiversity and Endemism

The Galápagos Islands are globally renowned for their rich biodiversity and high degree of endemism—species found nowhere else. This isolation, combined with diverse microclimates across the islands, has led to the evolution of distinct species. The island's flora and fauna have adapted to the harsh volcanic environment, creating a "living laboratory" of evolution.

Terrestrial Fauna

- Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra): The archipelago's namesake species, these giant tortoises are the largest living tortoises, with some individuals weighing over 400 kg (880 lbs). The Galápagos tortoise is divided into several subspecies, each adapted to specific islands and habitats. Once numbering in the hundreds of thousands, these tortoises were decimated by human activity, though conservation efforts have seen some success in restoring populations.

- Marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus): The only iguana species in the world that forages in the ocean, the marine iguana has adapted to feed on underwater algae, a rarity among reptiles. Their ability to dive up to 10 meters deep and their unique physiological adaptations, such as slowing their heart rate to conserve oxygen while submerged, make them an iconic species of the Galápagos.

- Galápagos land iguana (Conolophus spp.): Unlike its marine counterpart, the land iguana inhabits the arid regions of the islands, feeding primarily on cactus pads. Three species of land iguanas, including the pink land iguana (Conolophus marthae), were discovered only in 2009 and found exclusively on Volcán Wolf on Isabela Island.

- Darwin's finches: Perhaps the islands' most famous residents, Darwin's finches comprise 13 species of finches, each with variations in beak size and shape. These adaptations arose in response to the different food sources available on each island, such as seeds, insects, and even blood, as seen in the notorious vampire finch (Geospiza difficilis septentrionalis), which pecks at larger birds to feed on their blood.

- Flightless cormorant (Phalacrocorax harrisi): This bird has lost its ability to fly, having instead developed powerful legs and webbed feet that enable it to dive and swim effectively. Found only on the islands of Fernandina and Isabela, the flightless cormorant is an excellent example of adaptive evolution in a remote environment.

- Galápagos hawk (Buteo galapagoensis): As the archipelago's apex predator, the Galápagos hawk preys on various animals, including smaller birds, lizards, and even carrion. It plays a vital role in controlling populations of other species and maintaining ecological balance.

- Blue-footed booby (Sula nebouxii): This striking bird is easily recognizable by its bright blue feet, which play a role in courtship displays. Males with more vibrant feet are more likely to attract mates—the blue-footed booby nests on rocky shores across many of the islands.

- Galápagos penguin (Spheniscus mendiculus): The only penguin species to live north of the equator, the Galápagos penguin has adapted to the archipelago's warmer waters by relying on the cooling effects of the Humboldt and Cromwell Currents. This species primarily inhabits the western islands, such as Isabela and Fernandina.

- Waved albatross (Phoebastria irrorata): The only species of albatross to breed in the tropics, the waved albatross is endemic to Española Island. These birds mate for life and perform elaborate courtship dances each breeding season.

Marine Life

The surrounding waters of the Galápagos Islands are equally as rich in biodiversity as the land, mainly due to the upwelling of nutrient-rich waters that support a variety of marine organisms.

- Galápagos sea lion (Zalophus wollebaeki): These playful marine mammals are among the archipelago's most abundant and familiar species. Closely related to the California sea lion, they are smaller and more adapted to the tropical climate.

- Galápagos fur seal (Arctocephalus galapagoensis): The smallest of all fur seal species, the Galápagos fur seal spends much of its time in cooler waters. Due to their nocturnal feeding habits and rocky coastal habitats, they are more elusive than the more commonly seen sea lions.

- Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii): A subspecies of the green sea turtle, the Galápagos green turtle is the only turtle species to nest on the islands. Nesting occurs on many beaches throughout the archipelago, with Floreana Island being a significant site.

- Hammerhead sharks: The waters around the Galápagos, particularly around Darwin and Wolf islands, are known for large schools of scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini), making these locations some of the best shark-diving sites in the world.

- Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus): These gentle giants, the largest fish in the ocean, are commonly spotted in the Galápagos Marine Reserve, especially near the northern islands during the cooler months when nutrient-rich waters attract large schools of fish.

Flora

The plant life of the Galápagos is as varied as the animal species. The islands' flora ranges from coastal mangroves and salt-tolerant plants to lush highland forests.

- Opuntia cacti: Several species of Opuntia, or prickly pear cacti, are found throughout the islands. These cacti are a crucial food source for Galápagos tortoises and land iguanas. The size and shape of Opuntia vary greatly between islands, often reflecting the grazing pressure from local herbivores.

- Lava cacti (Brachycereus nesioticus): This cactus species grows directly on the barren lava fields of the younger islands, such as Fernandina and Isabela, thriving in harsh, arid conditions.

- Scalesia forests: Scalesia trees form dense forests in the higher altitudes of islands like Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal. Often referred to as the "Galápagos daisy tree," Scalesia plays a crucial role in the islands' highland ecosystems, providing habitat for various birds and insects.

- Miconia: Found in the highland regions of islands such as Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal, Miconia is a shrub that forms a dense understory, offering a habitat for many endemic species.

Human History of the Galápagos

The human history of the Galápagos is relatively brief compared to its natural history, but it has had significant impacts on the islands' ecosystems. The Galápagos were first discovered by European explorers in 1535 when the Spanish bishop Tomás de Berlanga stumbled upon the islands en route from Panama to Peru. He described the islands as "hell on earth," given their harsh, barren appearance.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the islands became a haven for pirates, who used them as a base to raid Spanish ships carrying treasure from the New World. Buccaneers and whalers arrived later, hunting the abundant sperm whales in the waters around the Galápagos and exploiting the islands' tortoises as a source of fresh meat, as tortoises could survive for months without food or water.

Ecuador annexed the Galápagos in 1832, establishing its first colony on Floreana Island, leading to the introduction of invasive species, such as goats, pigs, and rats, which have devastated the native flora and fauna.

Charles Darwin and the Birth of Evolutionary Theory

In 1835, Charles Darwin visited the Galápagos aboard HMS Beagle as part of a scientific expedition. Though he only spent five weeks on the islands, his observations of the diverse and unique species there laid the groundwork for his groundbreaking theory of natural selection. The variation he observed between finches, tortoises, and mockingbirds on different islands led him to conclude that species adapt over time to their environments—a realization that would ultimately culminate in his landmark 1859 work, On the Origin of Species.

Conservation and Threats

Despite their protected status, the Galápagos Islands face many conservation challenges. The introduction of invasive species, such as goats, pigs, and rats, has caused widespread ecological disruption. Goats, in particular, have decimated native vegetation on several islands, competing with endemic species like tortoises for food. Rats and pigs prey on the eggs of native birds, reptiles, and tortoises, posing a significant threat to the survival of these species.

The Galápagos National Park and Charles Darwin Research Station have implemented various conservation programs to combat these issues. Notable initiatives include eradicating invasive species, breeding programs for endangered animals (such as the captive breeding of tortoises), and habitat restoration projects. For example, on Isabela Island, goats were successfully eradicated on Isabela Island in one of history's largest invasive species eradication efforts.

Human activity, particularly tourism and fishing, poses additional threats. The islands receive over 200,000 visitors annually, and while ecotourism is carefully managed, the sheer volume of visitors can strain local resources and disturb wildlife. Illegal fishing, including harvesting sea cucumbers and sharks, remains a problem, particularly in the Galápagos Marine Reserve, established in 1998 to protect the archipelago's waters.

Climate change also presents a growing challenge, as rising sea temperatures and changing ocean currents threaten marine ecosystems and the species that rely on them. The cyclical El Niño phenomenon, which brings warm water and disrupts the upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich currents, has already led to the decline of species such as the Galápagos penguin and marine iguana.

Galápagos Marine Reserve

The Galápagos Marine Reserve is one of the largest marine protected areas in the world, covering 133,000 square kilometers (51,000 square miles). The reserve includes a variety of marine ecosystems, from deep-sea vents to coral reefs and mangroves. The diversity of marine life here is unparalleled, with many species endemic to the region. In addition to the iconic species mentioned earlier, the reserve is home to a wide range of fish, mollusks, crustaceans, and marine mammals.

The Darwin and Wolf Islands, located in the far north of the archipelago, are globally renowned as hotspots for marine biodiversity, particularly for large aggregations of sharks, including scalloped hammerheads and whale sharks. These areas are considered among the best diving locations in the world.

Conclusion

The Galápagos Islands are a unique and invaluable natural treasure, offering unparalleled insight into the processes of evolution, species adaptation, and ecological balance. Their isolation and diverse climates and environments have fostered a remarkable array of flora and fauna, much of which is found nowhere else on Earth. However, this uniqueness also makes the islands highly vulnerable to external threats such as invasive species, human activity, and climate change.

Conservation efforts have made significant strides in protecting the islands and their inhabitants, but continued vigilance is necessary to ensure that the Galápagos remain a "living laboratory" for future generations. As the world grapples with environmental degradation and biodiversity loss, the Galápagos stand as a powerful reminder of the fragile balance between species and their environments and the urgent need for global conservation efforts.

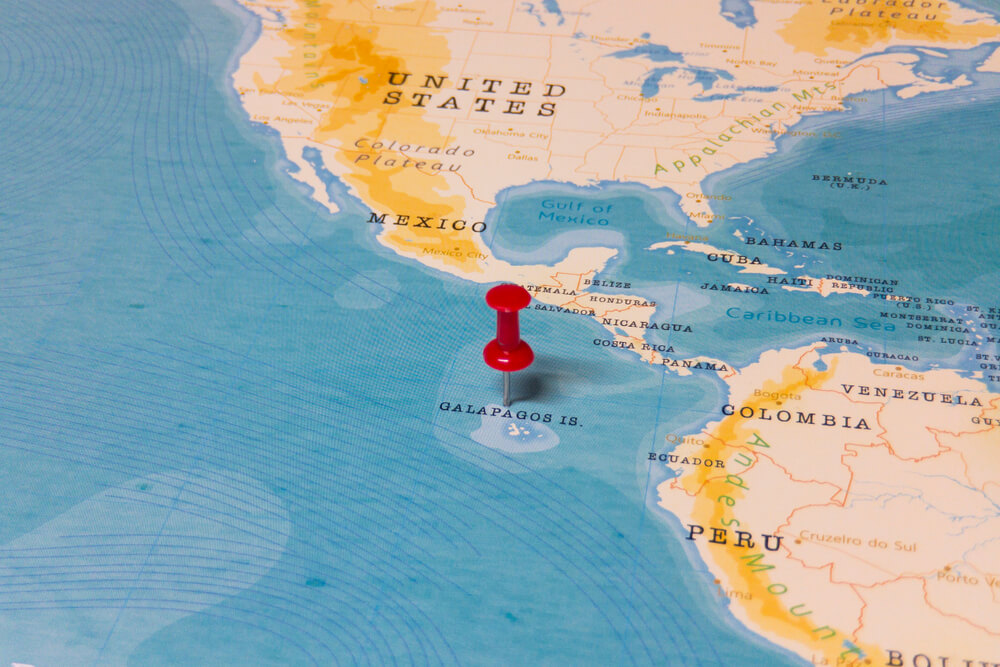

Galápagos Islands location map.

Main Islands

The 18 main islands (each having a land area of at least one sq km) of the archipelago (with their English names) are shown alphabetically.

Baltra (South Seymour) Island

Baltra is a small flat island located near the center of the Galápagos. It was created by geological uplift. The island is very arid, and its vegetation consists of salt bushes, prickly pear cacti, and palo santo trees.

Until 1986, Baltra (Seymour) Airport was the only airport serving the Galápagos. Now, two airports receive flights from the continent; the other is located on San Cristóbal Island. Private planes flying to Galápagos must fly to Baltra, as it is the only airport with facilities for planes overnight.

On arriving in Baltra, all visitors are immediately transported by bus to one of two docks. The first dock is in a small bay, where the boats cruising the Galápagos await passengers. The second is a ferry dock, which connects Baltra to the island of Santa Cruz.

During the 1940s, scientists moved 70 of Baltra's land iguanas to the neighboring North Seymour Island as part of an experiment. This move proved unexpectedly helpful when the native iguanas became extinct on Baltra due to the island's military occupation in World War II.

During the 1980s, iguanas from North Seymour were brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station as part of a breeding and repopulation project. In the 1990s, land iguanas were reintroduced to Baltra. As of 1997, scientists counted 97 iguanas living on Baltra, 13 of which had hatched on the islands.

Bartolomé (Bartholomew) Island

Bartolomé Island is a volcanic islet off the east coast of Santiago Island in the Galápagos Islands group. It is one of the "younger" islands in the Galápagos archipelago.

This island and neighboring Sulivan Bay on Santiago (James) Island are named after a lifelong friend of Charles Darwin, Sir Bartholomew James Sulivan, a lieutenant aboard HMS Beagle.

Today, Sulivan Bay is often misspelled as Sullivan Bay. This island is one of the few home to the Galápagos penguin, the only wild penguin species to live on the equator. The green turtle is another animal that resides on the island.

Darwin (Culpepper) Island

This island is named after Charles Darwin. It has an area of 1.1 sq km (0.42 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 168 m (551 ft). Here fur seals, frigates, marine iguanas, swallow-tailed gulls, sea lions, whales, marine turtles, and red-footed and Nazca boobies can be seen.

Española (Hood) Island

Its name was given in honor of Spain. It is also known as Hood, after Viscount Samuel Hood. It has an area of 60 sq km (23 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 206 m (676 ft). Española is the oldest island in the group, at around 3.5 million years, and the southernmost.

Due to its remote location, Española has many endemic species. It has its species of lava lizard, mockingbird and Galápagos tortoise. Española's marine iguanas exhibit a distinctive red coloration change during the breeding season.

Española is the only place where the waved albatross nests. Some birds have attempted to breed unsuccessfully on Genovesa (Tower) Island. Española's cliffs serve as the perfect runways for these birds, which take off for their ocean feeding grounds near the mainland of Ecuador and Peru.

Punta Suarez has migrant, resident, and endemic wildlife, including brightly colored marine iguanas, Española lava lizards, hood mockingbirds, swallow-tailed gulls, blue-footed boobies, Nazca boobies, red-billed tropicbirds, Galápagos hawks, three species of Darwin's finches, and the waved albatross.

Fernandina (Narborough) Island

The name was given in honor of King Ferdinand II of Aragon, who sponsored Columbus's voyage. Fernandina has an area of 642 sq km (248 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 1,494 m (4,902 ft). It is the youngest and westernmost island.

On May 13, 2005, a new, very eruptive process began on this island when an ash and water vapor cloud rose to a height of 7 km (23,000 ft), and lava flows descended the volcano's slopes on the way to the sea.

Punta Espinosa is a narrow stretch of land where hundreds of marine iguanas gather, primarily on black lava rocks. The famous flightless cormorants inhabit this island, as do Galápagos penguins, pelicans, Galápagos sea lions and Galápagos fur seals. Different types of lava flows can be compared, and mangrove forests can be observed.

Floreana (Charles or Santa María) Island

It was named after Juan José Flores, the first President of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago.

It is also called Santa Maria, after one of the caravels of Columbus. It has an area of 173 sq km (67 sq mi) and a maximum elevation of 640 m (2,100 ft). It is one of the islands with the most interesting human history and one of the earliest to be inhabited.

Flamingos and green sea turtles nest (December to May) on this island. The patapegada or Galápagos petrel, a sea bird that spends most of its life away from land, is found here.

At Post Office Bay, where 19th-century whalers kept a wooden barrel that served as a post office, mail could be picked up and delivered to its destinations, mainly Europe and the United States, by ships on their way home. At the "Devil's Crown," an underwater volcanic cone and coral formations are found.

Genovesa (Tower) Island

The name is derived from Genoa, Italy, the birthplace of Christopher Columbus. It has an area of 14 sq km (5.4 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 76 m (249 ft).

The remaining edge of a submerged large caldera forms this island. Its nickname, "The Bird Island," is justified.

At Darwin Bay, the only nocturnal gull species in the world, frigatebirds and swallow-tailed gulls can be seen. Red-footed boobies, noddy terns, lava gulls, tropic birds, doves, storm petrels and Darwin finches are also in sight.

Prince Philip's Steps is a bird-watching plateau with Nazca and red-footed boobies. There is a large Palo Santo forest.

Isabela (Albemarle) Island

This island was named in honor of Queen Isabela. With an area of 4,640 sq km (1,790 sq mi), it is the largest island in the Galápagos. Its highest point is Volcán Wolf, with an altitude of 1,707 m (5,600 ft). The island's seahorse shape is the product of the merging of six large volcanoes into a single land mass.

Galápagos penguins, flightless cormorants, marine iguanas, pelicans and Sally Lightfoot crabs abound on this island. At the skirts and calderas of the volcanoes of Isabela, land iguanas and Galápagos tortoises can be observed, as well as Darwin finches, Galápagos hawks, Galápagos doves, and fascinating lowland vegetation.

The third-largest human settlement of the archipelago, Puerto Villamil, is located at the southeastern tip of the island. It is the only island with the equator running across it. It is also the only place in the world where a penguin can be in its natural habitat in the Northern Hemisphere.

Marchena (Bindloe) Island

Named after Fray Antonio Marchena, it has an area of 130 sq km (50 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 343 m (1,125 ft). Galapagos hawks and sea lions inhabit this island, which is also home to the Marchena lava lizard, an endemic animal.

North Seymour Island

Its name was given after an English nobleman, Lord Hugh Seymour. It has an area of 1.9 sq km (0.73 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 28 m (92 ft).

This island is home to many blue-footed boobies and swallow-tailed gulls. It hosts one of the largest populations of frigate birds. It was formed from geological uplift.

Pinzón (Duncan) Island

Named after the Pinzón brothers, captains of the Pinta and Niña caravels, it has an area of 18 sq km (6.9 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 458 m (1,503 ft).

Pinta (Louis) Island

Named after the Pinta caravel, it has an area of 60 sq km (23 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 777 m (2,549 ft). Sea lions, Galápagos hawks, giant tortoises, marine iguanas, and dolphins can be seen here.

Pinta Island was home to the last remaining Pinta tortoise, Lonesome George. He was moved from Pinta Island to the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island, where scientists attempted to breed from him. However, Lonesome George died in June 2012 without producing any offspring.

Rábida (Jervis) Island

It bears the name of the convent of Rábida, where Columbus left his son during his voyage to the Americas. It has an area of 4.95 sq km (1.91 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 367 m (1,204 ft). The high amount of iron in the lava at Rábida gives it a distinctive red color.

White-cheeked pintail ducks live in a saltwater lagoon near the beach, where brown pelicans and boobies have built their nests. Until recently, flamingos were also found in the lagoon, but they have since moved on to other islands, likely due to a lack of food on Rábida. Nine species of finches have been reported on this island.

San Cristóbal (Chatham) Island

It bears the name of the patron saint of seafarers, "St. Christopher." Its English name was given after William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham. Its area is 558 sq km (215 sq mi), and its highest point rises to 730 m (2,400 ft).

This is the first island in the Galápagos Archipelago that Charles Darwin visited during his voyage on the Beagle. This island hosts frigate birds, sea lions, giant tortoises, blue- and red-footed boobies, tropicbirds, marine iguanas, dolphins and swallow-tailed gulls.

Its vegetation includes Calandrinia galapagos, Lecocarpus darwinii, and trees such as Lignum vitae. The largest freshwater lake in the archipelago, Laguna El Junco, is located in the highlands of San Cristóbal.

The capital of the province of Galápagos is Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, which lies at the southern tip of the island and is close to San Cristóbal Airport.

Santa Cruz (Indefatigable) Island

Given the name of the Holy Cross in Spanish, its English name derives from the British vessel HMS Indefatigable. It has an area of 986 sq km (381 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 864.5 m (2,836 ft).

Santa Cruz hosts the archipelago's most significant human population, Puerto Ayora. It also houses the Charles Darwin Research Station and the Galápagos National Park Service headquarters are here.

The GNPS and CDRS operate a tortoise breeding center here, where young tortoises are hatched, reared, and prepared to be reintroduced to their natural habitat.

The Highlands of Santa Cruz offer exuberant flora and are famous for the lava tunnels. Large tortoise populations are found here.

Black Turtle Cove is surrounded by mangroves, which sea turtles, rays, and small sharks sometimes use as mating areas. Cerro Dragón, known for its flamingo lagoon, is also located here, and along the trail, one may see land iguanas foraging.

Santa Fe (Barrington) Island

Named after a city in Spain, it has an area of 24 sq km (9.3 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 259 m (850 ft). Santa Fe hosts a forest of Opuntia cactus, which is the largest of the archipelago, and Palo Santo.

Weathered cliffs provide a haven for swallow-tailed gulls, red-billed tropic birds and shearwater petrels. Santa Fe species of land iguanas and lava lizards are often seen.

Santiago (San Salvador, James) Island

Its name is equivalent to Saint James in English; it is also known as San Salvador, after the first island discovered by Columbus in the Caribbean Sea.

This island has an area of 585 sq km (226 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 907 m (2,976 ft). Marine iguanas, sea lions, fur seals, land and sea turtles, flamingos, dolphins and sharks are found here.

Pigs and goats, introduced by humans to the islands and have caused great harm to the endemic species, have been eradicated (pigs by 2002; goats by the end of 2006).

Darwin finches, Galápagos hawks, and a colony of fur seals are usually seen. A recent (around 100 years ago) pahoehoe lava flow can be observed at Sulivan Bay.

Wolf (Wenman) Island

This island was named after the German geologist Theodor Wolf. It has an area of 1.3 sq km (0.50 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 253 m (830 ft).

Here, fur seals, frigatebirds, Nazca and red-footed boobies, marine iguanas, sharks, whales, dolphins and swallow-tailed gulls can be seen.

The most famous resident is the vampire finch, which feeds partly on blood pecked from other birds and is only found on this island.

Minor islands

Daphne Major

A small island directly north of Santa Cruz and directly west of Baltra, this very inaccessible island appears, though unnamed, on Ambrose Cowley's 1684 chart. It is vital as the location of multi-decade finch population studies by Peter and Rosemary Grant.

South Plaza Island (Plaza Sur)

It is named in honor of a former president of Ecuador, General Leónidas Plaza. It has an area of 0.13 sq km (0.050 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 23 m (75 ft).

The flora of South Plaza includes Opuntia cactus and Sesuvium plants, which form a reddish carpet on top of the lava formations.

Iguanas (land, marine and some hybrids of both species) are abundant, and large numbers of birds, including tropical birds and swallow-tailed gulls, can be observed from the cliffs on the southern part of the island, including tropical birds and swallow-tailed gulls.

Nameless Island

A small islet is mainly used for scuba diving.

Roca Redonda

An islet approximately 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Isabela. Herman Melville devotes the third and fourth sketches of The Encantadas to describing this islet (which he calls "Rock Rodondo") and its view.

Satellite photo of the Galápagos islands with names of the visible islands.