Valparaíso: The Jewel of the Pacific - Triumph, Tragedy, and Resilience

Valparaíso is a captivating blend of color, culture, and maritime heritage on Chile's Pacific coast. This vibrant port city boasts winding streets, colorful houses, and a bohemian spirit. The Historic Quarter is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that showcases its unique urban and architectural qualities.

The Colors and Scars of Valparaíso: A City's Five-Century Journey

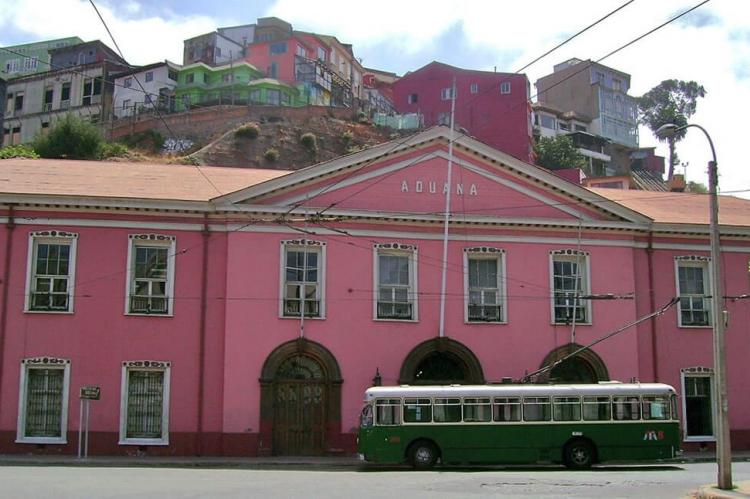

Clinging precariously to 45 steep hills overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Valparaíso stands as Chile's most visually captivating and culturally vibrant city—a UNESCO World Heritage Site where brightly painted houses cascade down hillsides like a waterfall of color, where historic funiculars defy gravity to connect the lower port with hillside neighborhoods, and where street art transforms crumbling walls into open-air galleries. Located approximately 120 kilometers (75 miles) northwest of Santiago on Chile's central coast, "Valpo" (as locals affectionately call it) served as South America's most important Pacific port during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet beneath Valparaíso's bohemian charm and artistic renaissance lies a city that has endured devastating earthquakes, catastrophic fires that have killed hundreds and destroyed tens of thousands of homes, economic decline, and ongoing struggles with poverty and inadequate infrastructure. This is the story of a city that refuses to surrender—where resilience, creativity, and cultural identity have persevered through triumph and tragedy across five centuries.

From Colonial Settlement to Pacific Gateway (1536-1914)

Valparaíso's origins date back to 1536, when Spanish conquistador Juan de Saavedra arrived in the natural bay. According to tradition, Saavedra named the settlement for his birthplace in Spain, though another version suggests soldiers called it "Val del Paraíso" (Paradise Valley). Before the Spanish arrival, the area was inhabited by Chango and Picunche Indigenous peoples who had developed fishing cultures adapted to the Pacific coast.

The colonial period saw slow development punctuated by repeated pirate raids. English, Dutch, and French corsairs attacked throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, forcing residents to rebuild repeatedly. Despite setbacks, Valparaíso's strategic importance for maritime communication between Spain and its South American colonies ensured survival.

Chile's independence from Spain in 1818 transformed Valparaíso's fortunes. The newly independent nation opened international trade that had previously been limited to Spain and its colonies. Valparaíso became the main harbor for the Chilean navy and the desired stopover for ships rounding South America via Cape Horn.

The 19th century marked Valparaíso's golden age. The city flourished into a bustling hub rivaling any port in the Americas, earning the nickname "Little San Francisco" and "Jewel of the Pacific." Waves of immigrants arrived from across the globe—British merchants, German technicians, French artisans, Italians, Croatians, Greeks, Chinese, and Japanese—transforming Valparaíso into a vibrant melting pot.

During this boom, Valparaíso led South America in innovation. In 1832, the city established Latin America's oldest stock exchange. In 1850, Chile's first volunteer fire department was founded. In 1827, El Mercurio de Valparaíso began publication—becoming the oldest Spanish-language newspaper in continuous publication in the world.

Between 1883 and 1916, 15 funicular elevators, or "ascensores," were constructed to connect the lower port (El Plan) with hillside neighborhoods (the cerros). These engineering marvels became iconic symbols of Valparaíso's unique topography. Wealthy merchants built grand mansions on hills like Cerro Alegre and Cerro Concepción, creating neighborhoods of ornate Victorian, Georgian, and Art Nouveau architecture.

Decline and the 20th Century Struggle (1914-2000)

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 dealt Valparaíso a devastating economic blow from which the city never fully recovered. Ships could now transit between oceans without the dangerous Cape Horn passage, eliminating Valparaíso's role as an essential stopover. Shipping traffic plummeted almost overnight.

The 20th century proved profoundly difficult. Economic decline accelerated as commerce shifted elsewhere. Wealthy families abandoned the city for Santiago or abroad. Grand mansions were subdivided, deteriorated, or abandoned. The city's population stagnated and even decreased as inhabitants moved to adjacent communities.

Natural disasters compounded economic challenges. A devastating 1906 earthquake required rebuilding much of the city. Subsequent major earthquakes in 1971, 1985, and 2010 caused repeated damage. By the late 20th century, Valparaíso had transformed from Chile's commercial capital into a struggling port city characterized by poverty, deteriorating infrastructure, and social challenges.

Cultural Renaissance and UNESCO Recognition (2000-2014)

Between 2000 and 2015, Valparaíso experienced a remarkable recovery as artists, tourists, and cultural entrepreneurs were attracted by the city's hillside historic districts, bohemian atmosphere, and affordable rents. Street art emerged as a defining characteristic—entire buildings became canvases for massive murals, transforming the city into an open-air gallery.

In 2003, UNESCO designated the Historic Quarter of the Seaport City of Valparaíso as a World Heritage Site, acknowledging it as "an excellent example of late 19th-century urban and architectural development in Latin America." The designation praised Valparaíso's natural amphitheatre setting and vernacular urban fabric adapted to hillsides.

Valparaíso developed its identity as Chile's cultural capital. Four large universities established the city as a major educational center. Chile's National Congress relocated from Santiago to Valparaíso in 1990. Cultural festivals proliferated, including internationally famous New Year's Eve fireworks displays visible along the entire coast.

The 2014 Catastrophe: Fire Destroys the Hills

On April 12, 2014, Valparaíso experienced one of its worst disasters. A wildfire, driven by extreme winds and dry conditions, raced through densely packed hillside neighborhoods with devastating ferocity.

The fire killed 15 people, seriously injured 10 others, destroyed approximately 2,900 houses, and left 11,000-12,000 people homeless. The disaster revealed systematic failures: insufficient equipment for volunteer firefighters, inadequate water pressure, empty fire hydrants, and narrow streets preventing emergency vehicle access.

The fire overwhelmingly affected poor communities living in informal settlements on the highest, steepest hills—areas never intended for dense residential development but occupied by families with no other housing options. These settlements consisted of houses built from flammable materials on steep slopes exposed to landslides, floods, and fire.

Reconstruction proved complex. Within four months, 1,600 emergency houses were installed alongside informal self-built structures. By 2017, a hybrid recovery emerged: 760 formal state-subsidized homes coexisted with 206 informal houses, 248 modified emergency houses, and 156 new informal extensions. By 2024, spatial analysis revealed 1,801 informal houses—dwellings that evolved from emergency shelters or were built without formal authorization.

The 2024 Mega-Fire: History Repeats as Tragedy

On February 2-3, 2024, history repeated itself with even more devastating consequences. Wildfires ignited during an extreme heatwave with temperatures reaching 40°C (104°F). The fires, driven by 25-knot (46 km/h or 29 mph) winds and fueled by vegetation dried by a decade-long mega-drought, became what scientists described as a "firestorm with tragic consequences."

The fires killed 134-136 people—Chile's deadliest fire in history—and destroyed approximately 14,000-15,000 homes, primarily in Viña del Mar and Quilpué. Over 36,000 hectares (89,000 acres) burned in the Valparaíso Region. In just twelve hours, the affected area increased nearly fivefold. The rapid spread overwhelmed all firefighting capacity.

President Gabriel Boric declared this "the worst catastrophe to hit the country since the earthquake of February 27, 2010." At the peak, 18,000 people were displaced. Basic services, including water, electricity, and telecommunications, were disrupted. The Viña del Mar Botanical Garden, founded in 1931, was destroyed.

The investigation revealed that the disaster was partly caused by arson. Authorities arrested three individuals, including two volunteer firefighters. By July 2025, nine individuals faced accusations connected to the tragedy.

Reconstruction costs were estimated at $1 billion. The pattern from 2014 threatened to repeat: formal rebuilding programs are often inaccessible to informal settlement residents who lack legal land title, leading to informal reconstruction that perpetuates vulnerability.

The Historic Quarter: Iconic Neighborhoods

Despite repeated catastrophes, Valparaíso's Historic Quarter retains extraordinary character.

Cerro Alegre (Joyful Hill) showcases Valparaíso at its most picturesque. Originally settled by English and German immigrants, the neighborhood features elegant Victorian and Georgian mansions painted in vibrant colors, narrow pedestrian passages, historic churches, and numerous boutique hotels, restaurants, and galleries.

Cerro Concepción (Conception Hill) neighbors Cerro Alegre and shares its architectural character. The Ascensor Concepción, constructed in 1883, connects the neighborhood to the waterfront. The cerro features the Palacio Baburizza (now the Museum of Fine Arts), Lutheran Church, Anglican Church of Saint Paul, and numerous cultural venues.

El Plan forms the commercial and port quarter along the waterfront. Plaza Sotomayor serves as the civic heart, surrounded by the Chilean Naval Command headquarters and neoclassical architecture. The port facilities retain historic character in sections accessible to visitors.

The Ascensores: Engineering Marvels

Valparaíso's ascensores are among the city's most distinctive features. These steeply inclined funiculars provide essential vertical transportation connecting El Plan with hillside neighborhoods. Several remain functional:

Ascensor Concepción (1883), the city's first funicular, climbs from Paseo Prat to Cerro Concepción.

Ascensor Artillería (1893) ascends from Plaza Aduana to Paseo 21 de Mayo, offering perhaps the finest panoramic views of the entire bay, port, and city.

Ascensor El Peral (1902) rises to Paseo Yugoslavo, providing access to the Palacio Baburizza and spectacular bay views.

In 1996, the World Monuments Fund declared Valparaíso's funicular lifts one of the world's 100 most endangered historical treasures.

Pablo Neruda and Literary Heritage

Valparaíso holds profound significance in Chilean literature as one of three homes of Nobel Prize-winning poet Pablo Neruda. Neruda purchased a house in the city in 1959, transforming it into La Sebastiana—one of his most beloved residences.

La Sebastiana, perched on Cerro Florida, reflects Neruda's passion for the sea and Valparaíso's bohemian spirit. The eccentric multi-level house features narrow staircases, numerous windows offering bay views, and collections of nautical objects and curiosities. The house now operates as a museum where visitors experience Neruda's aesthetic sensibilities.

Neruda's description captures the city's essence: "Valparaíso, how absurd you are... You haven't even combed your hair, you've never had time to dress, life always caught you unprepared."

Contemporary Challenges and Inequality

Beneath Valparaíso's colorful facades, serious socioeconomic challenges persist that repeatedly manifest during disasters. Valparaíso has the second-highest informal settlement population of any Chilean city. Families unable to afford formal housing occupy steep hillsides, constructing homes from salvaged materials without legal title, infrastructure, or essential services.

These informal settlements occupy Valparaíso's highest, steepest terrain—areas with the greatest environmental risk. The socioeconomic geography creates a city sharply divided between colorful historic houses attracting tourists on the lower hills and grey, invisible informal settlements higher up. During both the 2014 and 2024 fires, the poorest residents living in the most precarious housing on the steepest slopes suffered the greatest losses.

Tourism and Attractions

Despite challenges, Valparaíso attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors annually.

Street Art Tours offer immersive experiences of Valparaíso's open-air gallery, with expert guides explaining the artists, techniques, and messages behind the murals.

Funicular Rides on historic ascensores provide both transportation and spectacular views, offering visceral appreciation of Valparaíso's unique topography.

La Sebastiana, Pablo Neruda's house-museum, attracts literary enthusiasts and casual visitors.

Museums include the Museum of Fine Arts (Palacio Baburizza), the Natural History Museum, and the Naval and Maritime Museum.

Markets like Mercado Puerto offer authentic local experiences with fresh seafood and traditional Chilean dishes.

New Year's Eve brings spectacular fireworks displays visible from the entire bay, attracting tens of thousands of visitors.

The Path Forward: Resilience and Uncertainty

Valparaíso stands at a critical juncture. The city's extraordinary cultural heritage and UNESCO recognition coexist with persistent poverty, inadequate infrastructure, environmental vulnerability, and recurring catastrophic fires.

Recent disasters have exposed systemic challenges: inadequate water infrastructure, reliance on under-equipped volunteer firefighters, informal settlements in high-risk areas with no safe housing alternatives, insufficient resources for comprehensive reconstruction, and climate change intensifying drought and fire risk.

Fundamental questions persist: How can the city preserve historic character while ensuring residents have safe housing? How can informal settlement residents access housing security without displacement? How can reconstruction address root causes of vulnerability rather than reproducing patterns that guarantee future catastrophes?

Valparaíso's resilience has been tested repeatedly across five centuries. The city has survived pirate raids, earthquakes, economic collapse, and devastating fires. Each time, residents have rebuilt. Artists have created beauty from rubble. The bohemian spirit has persisted.

Yet resilience alone may be insufficient. Without addressing the structural inequalities, infrastructure deficits, and environmental vulnerabilities that repeatedly cause catastrophes, Valparaíso faces an uncertain future in which the next disaster always looms. The challenge is transforming resilience—the capacity to recover from disaster—into genuine sustainability that prevents catastrophes and ensures all residents can live safely.

Valparaíso remains the Jewel of the Pacific, but a jewel scarred by tragedy and still seeking the comprehensive renewal that would allow all its residents—not just tourists visiting colorful cerros—to experience the paradise its name promises.