The Panama Canal: Engineering Marvel Connecting Two Oceans

The Panama Canal stands as one of the most ambitious and consequential engineering achievements of the modern era—an artificial waterway spanning the Isthmus of Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific. Its construction claimed many lives, yet its completion revolutionized global commerce.

Cutting Through Continents: The Construction, Operation, and Expansion of the Panama Canal

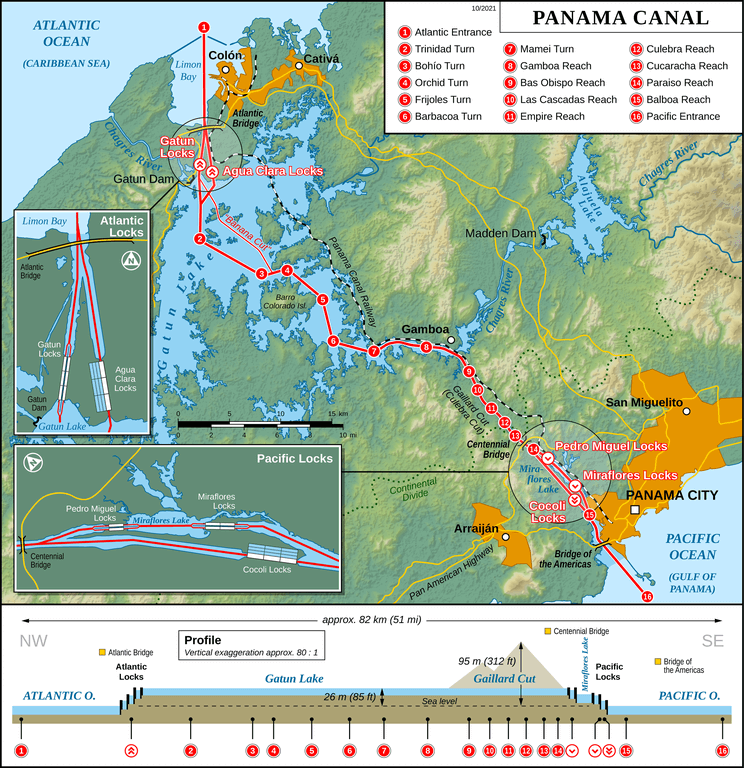

The Panama Canal stands as one of the most ambitious and consequential engineering achievements of the modern era—an artificial waterway spanning approximately 82 kilometers (51 miles) across the Isthmus of Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Since opening on August 15, 1914, this lock-type canal has fundamentally transformed global maritime trade, eliminating the need for ships to navigate the dangerous 15,000-kilometer (8,000-nautical-mile) voyage around South America's southern tip through either the Drake Passage or the Strait of Magellan.

The story encompasses heroic engineering, devastating failure, the conquest of tropical disease through medical innovation, and human suffering on an almost incomprehensible scale. Its construction claimed at least 27,000 lives over more than three decades. Yet its completion revolutionized global commerce and elevated the United States to new heights of international prestige and strategic power.

Today, managed by the Panama Canal Authority, the waterway facilitates more than 13,000 vessel transits annually, connecting approximately 180 maritime routes that link 170 countries and some 1,920 ports worldwide. The 2016 expansion doubled its capacity, allowing passage of vessels carrying up to 13,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), cementing its role as a critical artery of international trade.

The French Attempt: Vision and Catastrophe (1881-1889)

Ferdinand de Lesseps and Misplaced Confidence

The first serious attempt began with Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French diplomat and engineer who had overseen the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869. De Lesseps's achievement in Egypt—creating a 193-kilometer (120-mile) sea-level canal through relatively flat desert—had earned him international celebrity. When he announced in 1879, at age 74, that he would build an interoceanic canal in Central America, investors responded enthusiastically. Initial stock offerings were oversubscribed within three days.

De Lesseps's plan called for a sea-level canal similar to Suez with no locks. At the 1879 Congrès International d'Etudes du Canal Interoceanic in Paris, engineer Godin de Lépinay proposed a more feasible alternative: building dams to create an artificial lake accessed by locks. This design—containing all basic elements of what would eventually succeed—was dismissed by de Lesseps and most delegates, who lacked engineering expertise and were swayed by de Lesseps's charismatic confidence.

The Brutal Reality

Construction began on January 1, 1881. The French had assumed they faced a larger version of Suez. Instead, they encountered conditions so hostile that even well-paid French engineers struggled to remain. Unlike the flat Egyptian desert, Panama presented mountainous jungle terrain with elevations exceeding 100 meters (328 feet) at the continental divide. The Chagres River could rise 10 meters (33 feet) in a single day during rains, washing away months of excavation. Panama's geology proved treacherous, with massive landslides—sometimes exceeding 18 tons—thundering into excavations, burying equipment and refilling sections that had taken months to dig.

The French had estimated excavating approximately 80 million cubic meters (105 million cubic yards). Ultimately, they would excavate more than 76 million cubic meters (99 million cubic yards)—and the total project would eventually require over 238 million cubic meters (310 million cubic yards)—nearly four times the original estimate.

The Disease Catastrophe

Even more devastating were tropical diseases. Yellow fever and malaria killed on an industrial scale. An estimated three-quarters of French engineers died within three months of arriving. A Canadian doctor estimated 30 to 40 workers died daily during the wet seasons of 1882 and 1883.

The tragic irony was that the French actively created conditions that spread illness. Prevailing medical theory held that "miasma"—bad air from filth and rotting garbage—caused yellow fever and malaria. The French built elaborate hospital gardens with waterways around flowerbeds to protect plants from ants, and placed water pans under bedposts to keep ants off patients. Both well-intentioned measures created perfect breeding sites for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (yellow fever vectors) and Anopheles mosquitoes (malaria vectors). Patients often contracted diseases in the hospital itself.

Conservative estimates suggest approximately 22,000 workers died during the French effort between 1881 and 1889, though some historians place the figure as high as 25,000. Most victims were Caribbean laborers from Jamaica, Martinique, and other islands.

Financial Collapse

By 1887, the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interoceanique faced financial disaster. De Lesseps had abandoned his sea-level plan in favor of locks, admitting critics were correct, but it was too late. Costs spiraled far beyond projections. On February 4, 1889, the company declared bankruptcy. The collapse triggered a massive scandal. An estimated 800,000 French citizens had invested their savings, resulting in a loss of approximately 2 billion francs (equivalent to roughly $9 billion today). De Lesseps died in disgrace in 1894, his reputation destroyed.

The American Era: Disease Control and Engineering Triumph (1904-1914)

Geopolitical Maneuvering

American interest intensified during the Spanish-American War of 1898, when the battleship USS Oregon required 67 days to travel from San Francisco around South America to Cuba—highlighting the strategic value of a Central American canal. After the French company dropped its asking price from $109 million to $40 million and clever lobbying emphasized Panama's advantages, the U.S. Senate voted 42-34 in favor of the Panama route on June 19, 1902.

One obstacle remained: Panama was a province of Colombia, which rejected the proposed treaty in August 1903. President Theodore Roosevelt supported Panamanian separatists. A carefully orchestrated revolution occurred on November 3, 1903; Panama declared independence on November 4; and on November 18, Panama's representative signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, granting the United States rights to build and operate a canal "in perpetuity" in a zone approximately 16 kilometers (10 miles) wide—the Panama Canal Zone.

The Conquest of Disease

Before construction could begin, the Americans had to solve the disease problem. President Roosevelt appointed Dr. William Crawford Gorgas as the chief sanitation officer. Gorgas brought critical experience from successfully controlling yellow fever in Havana after it was confirmed in 1900 that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes transmitted the disease.

Gorgas's program was systematic: teams fumigated buildings to kill adult mosquitoes; every container holding water was eliminated, screened, or treated with oil; extensive drainage networks were constructed; piped water systems eliminated the need for water storage; buildings had windows and doors fitted with screens; and hospital wards were screened and isolated.

The results were dramatic. Yellow fever cases declined from 340 in 1905 to zero by November 1906—the first time in centuries that Panama had been free of the disease. Malaria infection rates dropped significantly. The death rate from disease fell from approximately 11.59 per 1,000 in November 1906 to 1.23 per 1,000 in December 1909—lower than many American cities. Gorgas's achievement was essential to the canal's completion and pioneered mosquito control measures applied worldwide.

Engineering Leadership and Design

John Frank Stevens arrived as chief engineer in July 1905, recognizing that infrastructure had to precede canal construction. Stevens rebuilt the Panama Railroad, constructed warehouses, housing, hospitals, and support facilities, and imported thousands of pieces of heavy equipment.

Stevens made the crucial decision that the canal would use a lock-and-lake design. After extensive study, he concluded that a sea-level canal was impractical due to the Chagres River's massive flooding. His design involved damming the Chagres River to create Gatun Lake at approximately 26 meters (85 feet) above sea level. Ships would be raised by locks at the Atlantic entrance, transit across the lake, and through the Culebra Cut, then be lowered by locks to the Pacific. This reduced excavation by about 40 percent compared to a sea-level canal.

Stevens resigned in 1907 and was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel George Washington Goethals of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Roosevelt placed the project under military leadership, giving Goethals dictatorial powers over the Canal Zone. Goethals would oversee the project to completion.

The Construction Effort

At its peak in 1913, more than 40,000 workers from numerous countries labored on the project. Working conditions were difficult but dramatically better than during the French era, with housing, clean water, medical care, and adequate food provided.

Gatun Dam and Locks: The Gatun Dam was the largest earth dam in the world at completion, approximately 2.4 kilometers (1.5 miles) long and 32 meters (105 feet) above sea level. It created Gatun Lake, which became the world's largest artificial lake, covering approximately 425 square kilometers (164 square miles). The adjacent Gatun Locks lift ships in three stages. Each lock chamber is 33.5 meters (110 feet) wide and 320 meters (1,050 feet) long. The largest lock gates are 25 meters (82 feet) high, 2.1 meters (7 feet) thick, and weigh up to 745 metric tons (800 short tons), yet 37-kilowatt (50-horsepower) motors can open or close them in two minutes.

Culebra Cut (Gaillard Cut): The most challenging excavation cut through the continental divide. This section presented the same landslide problems that plagued the French but on a larger scale. Engineers ultimately excavated more than 88 million cubic meters (115 million cubic yards)—far exceeding the French excavation. The cut remains one of the canal's most impressive features, with nearly vertical walls rising 152 meters (500 feet) in places.

Pacific Locks: The Pedro Miguel Locks lower ships approximately 9 meters (31 feet) to Miraflores Lake. The Miraflores Locks then lower ships in two stages to the Pacific sea level. These locks had to accommodate the Pacific's significant tidal range—up to 6 meters (20 feet) at spring tides, compared to less than 1 meter (3 feet) on the Atlantic side.

Opening

By 1913, the canal was essentially complete. The official opening occurred on August 15, 1914, when the cargo ship SS Ancon made the first official transit. This momentous achievement received little international attention, as World War I had begun in Europe days earlier, dominating headlines. The canal was completed six months ahead of schedule and approximately $23 million under the $375 million budget.

Construction claimed approximately 5,600 American-era lives. Combined with French casualties, total deaths exceeded 27,000 people, making it one of history's costliest construction projects in terms of human life.

How the Canal Works

The Panama Canal operates as a lock-type canal, lifting and lowering ships through water-filled chambers to traverse elevated Gatun Lake. A complete transit takes approximately 8 to 10 hours, covering the 82-kilometer (51-mile) route.

Ships entering from the Atlantic navigate through Limon Bay to Gatun Locks. Small electric locomotives called "mules" attach cables and guide vessels precisely through narrow lock chambers. The ship enters the first chamber, and massive gates close. Water from Gatun Lake flows through culverts, filling the chamber in 8 to 10 minutes. This repeats twice more until the vessel has been raised 26 meters (85 feet) to lake level.

Ships cross Gatun Lake following a dredged channel, then enter the Culebra Cut—the narrowest portion at 152 meters (500 feet) wide. They proceed through Pedro Miguel Locks (one step down 9 meters), cross Miraflores Lake, then descend through Miraflores Locks (two stages totaling approximately 16.5 meters) to the Pacific sea level.

Each ship that transits through original locks consumes approximately 197 million liters (52 million gallons) of fresh water—enough to supply a city of 50,000 for one day. This water must be continuously replenished by tropical rainfall, creating vulnerability to drought.

The 2016 Expansion

The Panamax Limitation

Original canal locks imposed size restrictions: "Panamax" vessels could be 294 meters (965 feet) long, 32.3 meters (106 feet) wide, with a 12-meter (39.5-foot) draft. For decades, ship designers built to these dimensions. However, global shipping evolved with container ships growing ever larger. "Post-Panamax" vessels exceeding these dimensions could not use the canal, forcing them to take routes around South America or through the Suez Canal.

The Third Lane

In 2006, Panamanians voted to approve a $5.25 billion expansion project to build a new, larger lane. Construction began in 2007 and was completed in 2016. The expansion added two new lock complexes:

Agua Clara Locks (Atlantic side) and Cocoli Locks (Pacific side) accommodate "New Panamax" vessels up to 366 meters (1,201 feet) long, 49 meters (161 feet) wide, with 15.2-meter (50-foot) draft—allowing container ships carrying up to 13,000-14,000 TEUs, more than double Panamax capacity.

The new locks incorporate technological improvements: water-saving basins recycle approximately 60 percent of water; massive rolling gates (3,100 metric tons each) slide horizontally rather than swinging; and tugboats position ships instead of locomotives.

The expanded canal opened on June 26, 2016, successfully increasing capacity and allowing passage of approximately 98 percent of the world's container ship fleet.

Economic and Strategic Importance

The Panama Canal handles approximately 6 percent of world trade. In fiscal year 2023, it recorded 423.8 million tons of cargo, generating roughly $4.99 billion in revenue. Primary commodities include containerized cargo, petroleum products, grains, mineral ores, and vehicles.

The canal shortened maritime routes dramatically:

- New York to San Francisco: Reduced from approximately 22,500 kilometers (12,000 nautical miles) to 9,500 kilometers (5,200 nautical miles)—a 58 percent reduction

- Europe to East Asia: Shortened by approximately 3,700 kilometers (2,000 nautical miles)

Beyond economics, the canal holds immense strategic value for naval operations. The 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaties transferred control to Panama, culminating in full sovereignty on December 31, 1999. The Panama Canal Authority has operated efficiently and profitably since its inception, investing billions in maintenance and improvements.

Future Challenges

The canal faces several challenges: competition from the Suez Canal and potential Arctic routes; larger "Megamax" vessels (18,000-24,000 TEUs) too big even for expanded locks; water scarcity from climate change (severe droughts in 2019 and 2023 forced restrictions); and environmental sustainability pressures regarding water consumption and watershed management.

Climate change poses both threats and uncertainties, with Panama potentially experiencing more variable rainfall. The Panama Canal Authority works to promote sustainable land use and watershed protection, with approximately 40 percent of the watershed currently protected.

Conclusion

The Panama Canal stands as a testament to human ambition, engineering ingenuity, medical innovation, and perseverance. From the catastrophic French failure to the American triumph, the canal's story encompasses tragedy and achievement. More than a century after opening, it remains central to global maritime trade, connecting approximately 180 routes linking 170 countries.

The 2016 expansion ensures continued relevance, while successful Panamanian management demonstrates that the waterway thrives under local sovereignty. The canal's future faces opportunities and challenges, yet its geographic position, efficient operation, and continuous adaptation suggest it will remain a vital artery of international commerce for generations—a narrow passage that has fundamentally reshaped how the world connects and trades across vast oceanic distances.

Map illustrating the Panama Canal and its locks.