The Atacama Desert: Earth's Most Arid Frontier

The Atacama Desert, stretching along Chile's Pacific coast, is not merely a geographical marvel but an intricate mosaic of history, ecology, and adaptation. Beyond its arid expanses lies the Atacama Desert Ecoregion, an ecological classification that extends its influence across adjacent areas.

Beyond Barren: The Hidden Life and Global Significance of the Atacama Desert

Stretching across the western edge of South America like a vast, otherworldly landscape, the Atacama Desert represents the most arid non-polar region on Earth, where some weather stations have never recorded measurable precipitation and others have experienced intervals of over 400 years without rainfall. Extending approximately 1,600 kilometers (995 miles) along Chile's Pacific coast and covering roughly 105,000 square kilometers (40,540 square miles), this extraordinary desert ecosystem occupies a narrow strip between the towering Andes Mountains and the cold Pacific Ocean, creating conditions so extreme that they serve as terrestrial analogues for Mars exploration research.

Despite its reputation as a lifeless wasteland, the Atacama Desert supports remarkable biodiversity, unique geological formations, and Indigenous cultures that have adapted to survive in one of Earth's most challenging environments. The desert's pristine skies, mineral wealth, and extreme ecological conditions have made it a focal point for astronomical research, mining activities, and conservation efforts aimed at protecting one of the planet's most unusual and scientifically valuable ecosystems.

Geographic Extent and Boundaries

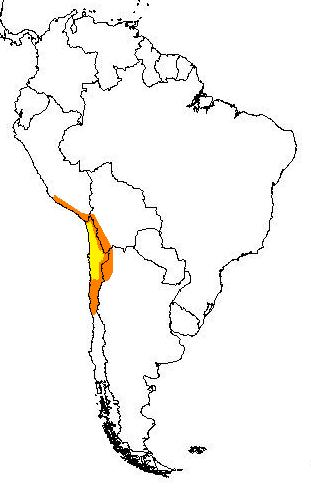

The Atacama Desert extends from the Loa River in northern Chile near the Peruvian border to the Aconcagua River north of Santiago, encompassing portions of the Arica y Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, Atacama, and Coquimbo regions. The desert's northern boundary merges with the Sechura Desert of Peru, while its southern limit transitions into the Mediterranean climate zone of central Chile.

The western boundary follows the Pacific coastline, where the cold Humboldt Current creates a marine influence that moderates temperatures while contributing to the region's extreme aridity through thermal inversion effects. The eastern boundary rises into the Andes Mountains, where elevation-induced precipitation creates distinct altitudinal zones that support different vegetation communities and ecological processes.

Within this geographic framework, the Atacama Desert encompasses multiple distinct zones, including the hyperarid core, coastal fog zones, salt flats, high-altitude plateaus, and transitional areas that connect with adjacent ecosystems. This internal diversity creates a complex mosaic of habitats that support specialized communities adapted to specific combinations of elevation, moisture availability, and substrate conditions.

Geological Foundation and Landscape Formation

Tectonic Setting and Crustal Evolution

The Atacama Desert's geological foundation reflects its position within one of Earth's most tectonically active regions, where the oceanic Nazca Plate subducts beneath the continental South American Plate. This ongoing subduction process has created the Andes Mountains, generating volcanic activity and mineral deposits that characterize much of the desert's landscape.

The desert contains some of the world's richest copper deposits, formed through hydrothermal processes associated with Andean volcanism over millions of years. The Chuquicamata mine, one of the largest open-pit copper mines on Earth, exemplifies the scale of mineral resources contained within the desert's geological formations.

Ancient basement rocks, some dating back over 2 billion years, are exposed in portions of the coastal range, providing insights into South America's earliest geological history. These Precambrian formations have been extensively modified by subsequent tectonic activity, creating complex structural patterns that influence modern drainage systems and groundwater flow.

Volcanic Landscapes and Geothermal Features

Active and extinct volcanoes throughout the Atacama Desert create distinctive landscape features while contributing to the region's unique chemical and thermal environments. The El Tatio geyser field, located at over 4,300 meters (14,100 feet) elevation, represents one of the world's highest geyser fields and demonstrates the ongoing geothermal activity associated with Andean volcanism.

Volcanic deposits cover extensive areas of the desert, creating substrates with unique chemical compositions that support specialized plant communities. Salt flats formed through volcanic activity and subsequent evaporation processes create some of the most extreme environments within the desert, where only the most specialized organisms can survive.

Lava flows, volcanic cones, and pyroclastic deposits create complex topographic patterns that influence local climate conditions and water availability. These volcanic landscapes often contain unique microhabitats where specialized species have evolved in isolation from surrounding areas.

Salt Flats and Evaporite Deposits

The Atacama Desert contains numerous salt flats, or salares, that represent some of the most extreme environments on Earth. The Salar de Atacama, covering over 3,000 square kilometers (1,158 square miles), contains the world's largest lithium reserves while supporting unique ecosystems adapted to hypersaline conditions.

These salt flats form through the evaporation of ancient lakes and continued groundwater discharge in areas with no external drainage. The resulting evaporite deposits contain complex mineral assemblages including halite, gypsum, and various rare minerals that create unique chemical environments for specialized organisms.

Flamingo populations utilize some salt flats for feeding and breeding, creating striking contrasts between vibrant wildlife and stark mineral landscapes. These oases of biological activity within the hyperarid desert demonstrate the importance of water availability in determining ecosystem structure and function.

Climate Systems and Extreme Aridity

Causes of Hyperaridity

The Atacama Desert's extreme aridity is a result of a unique combination of geographic and atmospheric factors that create what climatologists term a "perfect storm" of drying conditions. The cold Humboldt Current along the Pacific coast creates thermal inversions that prevent cloud formation and precipitation, while the rain shadow effect of the Andes Mountains blocks moisture from the Amazon Basin.

High-pressure systems associated with the South Pacific Anticyclone create persistent subsidence that inhibits cloud formation and maintains clear skies throughout most of the year. These atmospheric conditions, combined with the desert's position between two major mountain ranges, create some of the most stable and arid climate conditions found anywhere on Earth.

Annual precipitation across much of the desert averages less than 1 mm (0.04 inches), with some areas receiving no measurable rainfall for decades. The Calama weather station has recorded annual precipitation totals of 0.0 mm for multiple consecutive years, while some locations may experience centuries without significant rainfall events.

Temperature Patterns and Diurnal Variations

Despite its extreme aridity, the Atacama Desert experiences relatively moderate temperatures due to its coastal location and elevation variations. Coastal areas typically experience temperatures ranging from 15-25°C (59-77°F) throughout the year, while inland areas may experience greater temperature variations.

Diurnal temperature fluctuations can be extreme, particularly at higher elevations where nighttime temperatures may drop below freezing while daytime temperatures exceed 25°C (77°F). These temperature variations create significant stress for organisms while contributing to physical weathering processes that shape the desert landscape.

Clear skies and low humidity allow rapid radiational cooling at night, creating temperature inversions that can trap moisture near the ground surface. This phenomenon contributes to fog formation in coastal areas and dew formation in some inland locations, providing crucial moisture sources for desert organisms.

Fog Systems and Coastal Moisture

Coastal areas of the Atacama Desert receive significant moisture input through fog formation, despite the absence of rainfall. Marine fog forms when warm, moist air from the Pacific Ocean encounters the cold waters of the Humboldt Current, creating persistent fog banks that penetrate several kilometers inland.

This fog represents a crucial water source for coastal ecosystems, with some areas receiving the equivalent of 50-200 mm (2-8 inches) of annual precipitation through fog capture. Specialized vegetation communities have evolved to harvest fog water through various morphological and physiological adaptations.

Fog harvesting systems, both natural and artificial, demonstrate the potential for utilizing atmospheric moisture in extremely arid environments. These systems offer valuable insights into water conservation strategies, supporting both natural ecosystems and human communities in water-scarce regions.

Vegetation Communities and Plant Adaptations

Hyperarid Zone Flora

The hyperarid core of the Atacama Desert, where annual precipitation approaches zero, supports remarkably sparse vegetation communities dominated by highly specialized species capable of surviving extreme drought conditions. Many areas remain essentially devoid of visible plant life, creating landscapes that resemble lunar or Martian surfaces.

Where vegetation does occur in hyperarid zones, it typically consists of scattered individuals of extremely drought-tolerant species separated by vast expanses of bare ground. These plants often exhibit CAM photosynthesis, succulent water storage tissues, and extensive root systems that can extract moisture from minimal soil sources.

Cryptobiotic soil crusts, composed of cyanobacteria, lichens, and specialized bacteria, play crucial roles in hyperarid ecosystems by stabilizing soils, fixing nitrogen, and creating microsites that are favorable for seed germination. These living soil surfaces represent some of the most important biological components of hyperarid desert ecosystems.

Coastal Fog Zone Vegetation

Areas influenced by coastal fog support more diverse and productive vegetation communities than hyperarid inland zones. The Lomas formations, found along the seaside slopes, create seasonal ecosystems that flourish during winter fog seasons and enter dormancy during dry periods.

Endemic plant species within fog zones demonstrate remarkable adaptations for fog capture, including specialized leaf surfaces, pubescence patterns, and growth forms that maximize water collection efficiency. Many species complete their entire life cycles during brief periods of fog-enhanced moisture availability.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation phenomenon occasionally brings increased precipitation to coastal areas, triggering spectacular blooming events where normally barren areas become carpeted with wildflowers. These episodic events demonstrate the potential for rapid ecosystem response to increased moisture availability.

High-Altitude Plant Communities

Higher elevation areas within the Atacama Desert, particularly approaching the Andes Mountains, support distinct plant communities adapted to cold temperatures, intense solar radiation, and seasonal precipitation patterns. These communities often resemble high-altitude ecosystems found in other arid mountain regions worldwide.

Cushion plants, bunch grasses, and specialized shrubs dominate high-elevation communities, demonstrating adaptations to temperature extremes, intense ultraviolet radiation, and seasonal water availability. Many species show remarkable longevity, with some cushion plants estimated to be several hundred years old.

Seasonal wetlands at high elevations support unique plant communities that take advantage of snowmelt and occasional precipitation events. These temporary aquatic systems create oases of biological activity within the broader arid landscape, providing crucial habitats for specialized aquatic plants and animals.

Endemic Species and Evolutionary Adaptations

The Atacama Desert supports hundreds of endemic plant species that have evolved unique adaptations to extreme aridity. These species often occupy highly specialized niches defined by specific combinations of substrate, elevation, and microclimate conditions.

Copiapoa cacti, endemic to the Atacama region, demonstrate remarkable drought tolerance and longevity, with some individuals estimated to be over 100 years old. These cacti exhibit specialized water storage capabilities and can survive extended periods without any water input.

Desert shrubs, including various Atriplex and Frankenia species, show adaptations for salt tolerance, allowing them to utilize saline groundwater sources unavailable to less specialized plants. These halophytic adaptations expand the range of habitats available for plant colonization within the desert ecosystem.

Fauna and Animal Adaptations

Vertebrate Communities

Despite extreme environmental conditions, the Atacama Desert supports diverse vertebrate communities that demonstrate remarkable adaptations to aridity and resource scarcity. Large mammals are generally rare, though guanacos occur in areas with sufficient vegetation and water availability.

The vicuña, the smallest member of the South American camelid family, inhabits high-elevation areas where seasonal precipitation supports grassland communities. These animals demonstrate exceptional water conservation abilities and can survive on vegetation with very low moisture content.

Reptile diversity reaches surprisingly high levels, with numerous endemic lizard species adapted to specific habitat conditions throughout the desert. These species often exhibit behavioral and physiological adaptations that allow them to function in environments with extreme temperature variations and minimal water availability.

Bird Communities and Migration Patterns

Bird diversity within the Atacama Desert reflects the region's habitat heterogeneity, with different species assemblages occupying coastal areas, inland desert zones, and high-elevation wetlands. Many species demonstrate remarkable behavioral adaptations for surviving in water-scarce environments.

Flamingo species, including Chilean, Andean, and James's flamingos, utilize high-altitude salt lakes for feeding and breeding. These specialized waterbirds have evolved physiological adaptations that enable them to process hypersaline water while maintaining water balance in extremely arid conditions.

Raptors, including various hawk and falcon species, occupy the desert ecosystem as top predators, often ranging over vast territories in search of prey. These birds demonstrate exceptional flight capabilities and energy conservation strategies adapted to the sparse prey resources available in desert environments.

Invertebrate Diversity and Specialization

Invertebrate communities within the Atacama Desert show exceptional diversity and endemism levels, with many species adapted to highly specific microhabitat conditions. Arthropods, particularly beetles and spiders, demonstrate remarkable adaptations for water conservation and temperature regulation.

Darkling beetles exhibit specialized behaviors for fog water collection, positioning themselves on ridges during fog events to collect water on their body surfaces. These behavioral adaptations enable them to obtain water in environments where free water is scarce or unavailable.

Soil invertebrates, including various nematode species, demonstrate cryptobiotic capabilities that allow them to survive extended periods of complete desiccation. These adaptations enable persistence in environments that experience years or decades without significant moisture input.

WWF Ecoregion Classification and Biodiversity Assessment

Atacama Desert Ecoregion

The WWF Atacama Desert ecoregion encompasses the core hyperarid zone of the desert, covering approximately 105,000 square kilometers (40,540 square miles) primarily within Chile, with smaller extensions into Peru and Bolivia. This ecoregion represents one of the most extreme terrestrial environments on Earth, characterized by minimal precipitation, sparse vegetation, and highly specialized biological communities.

Within the broader ecoregion, distinct subregions reflect variations in elevation, proximity to the coast, and geological substrate. The coastal fog zone supports higher biological diversity than inland hyperarid areas, while high-elevation zones transition toward Andean ecosystems with different species assemblages and ecological processes.

The ecoregion's conservation status reflects both the extreme conditions that limit human activities and the increasing pressures from mining, tourism, and infrastructure development. Many areas remain in relatively pristine condition due to their inhospitable nature, though localized impacts can be severe where growth occurs.

Sechura Desert Transition

The northern boundary of the Atacama Desert transitions into the Sechura Desert of Peru, creating ecotonal areas that support unique species assemblages and demonstrate biogeographic connections between different desert systems. These transition zones often support higher species diversity than core desert areas due to the mixing of floras from other regions.

Seasonal precipitation patterns in transitional areas create periodic blooming events that support migratory species and demonstrate the potential for rapid ecosystem response to increased moisture availability. These events offer crucial insights into the dynamics and resilience of desert ecosystems.

The transition zone's conservation significance includes its role as a corridor for species movement and genetic exchange between desert systems, making it particularly important for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem connectivity across the broader arid region of western South America.

Mediterranean Scrub Transition

The southern boundary of the Atacama Desert transitions into Mediterranean-climate ecosystems in central Chile, creating complex ecotonal patterns that support high levels of species diversity and endemism. These transition areas experience winter rainfall that supports different vegetation communities than pure desert ecosystems.

Sclerophyllous shrublands and seasonal grasslands in transition areas provide habitat for species adapted to intermediate moisture conditions while serving as refugia during extreme drought periods. These areas often support the highest plant and animal diversity within the broader desert region.

The Mediterranean transition zone faces significant conservation challenges from urban development, agriculture, and infrastructure expansion associated with Chile's central population centers. Protection of these transition areas is crucial for maintaining ecosystem connectivity and supporting species adapted to intermediate environmental conditions.

Protected Areas and Conservation Framework

National Parks and Reserves

Protected area coverage within the Atacama Desert has expanded significantly over recent decades, though the ecosystem's extreme conditions and remoteness have historically limited both human impacts and formal conservation efforts. Major protected areas include Lauca National Park, which protects high-elevation wetlands and wildlife populations, and Pan de Azúcar National Park, which conserves coastal desert ecosystems.

Llanos de Challe National Park protects some of the world's most significant fog-dependent ecosystems while providing habitat for numerous endemic plant species. The park's location in the coastal fog zone makes it particularly important for conserving species adapted to this unique moisture regime.

Valle de la Luna Natural Monument preserves spectacular geological formations while protecting representative samples of hyperarid desert ecosystems. The area's Moon Valley landscapes demonstrate the extreme erosional processes that shape desert environments while providing habitat for specialized desert organisms.

High-Altitude Wetland Protection

High-elevation wetlands within the Atacama Desert, including salt lakes and seasonal pools, receive protection through various national parks and reserves. These aquatic systems support disproportionately high biodiversity compared to surrounding desert areas while providing crucial habitat for flamingo populations and other specialized wildlife.

Salar de Tara National Reserve protects important flamingo breeding habitat while conserving unique high-altitude desert ecosystems. The reserve's management focuses on maintaining water levels and quality necessary to support wildlife populations while managing the impacts of tourism.

International recognition through the Ramsar Convention designation acknowledges the global significance of the Atacama wetlands for migratory bird conservation, while promoting international cooperation for the protection and management of these ecosystems.

Transboundary Conservation Initiatives

The transboundary nature of the Atacama Desert ecosystem requires international cooperation between Chile, Peru, and Bolivia for effective conservation. Collaborative programs address shared conservation challenges, including the protection of migratory species, habitat connectivity, and climate change adaptation.

The Tropical Andes Biodiversity Hotspot designation recognizes the conservation significance of transition zones between desert and mountain ecosystems while promoting coordinated conservation efforts across national boundaries. These programs focus on protecting habitat corridors and maintaining ecosystem connectivity.

International research collaborations studying desert ecology, climate change impacts, and conservation strategies contribute to global understanding of arid ecosystem management while building local capacity for conservation and sustainable development.

Ecological Processes and Ecosystem Functions

Water Cycling and Moisture Sources

Water cycling within the Atacama Desert operates through mechanisms vastly different from those in mesic ecosystems, with fog, dew, and rare precipitation events providing the primary sources of moisture. These limited water sources create complex spatial and temporal patterns of resource availability, which in turn drive ecosystem structure and function.

Fog water represents a crucial input in coastal areas, with specialized vegetation communities harvesting atmospheric moisture through morphological and behavioral adaptations. The efficiency of fog capture varies significantly among species and locations, creating microhabitat differences that influence community composition.

Groundwater systems, though limited, provide moisture sources in some areas through capillary action and occasional surface expression. These groundwater-dependent ecosystems often support higher biological diversity than surrounding areas while demonstrating the importance of subsurface hydrology in desert ecosystem function.

Nutrient Cycling and Soil Development

Nutrient cycling within Atacama Desert ecosystems operates under severe moisture limitations that constrain biological processes and slow decomposition rates. Organic matter accumulation remains minimal due to low primary productivity and rapid decomposition during brief periods of moisture availability.

Nitrogen fixation occurs primarily through cryptobiotic soil crusts and specialized plant-microbe associations, with rates much lower than those found in mesic ecosystems. The limited nitrogen availability constrains primary productivity while creating strong competitive relationships among plant species.

Soil development proceeds extremely slowly due to minimal water availability and limited biological activity. Many desert soils show little profile development despite their potentially great age, though chemical weathering processes continue to operate under hyperarid conditions.

Disturbance Regimes and Ecosystem Dynamics

Natural disturbance regimes within the Atacama Desert include periodic drought intensification, rare flood events, and volcanic activity, which create temporal and spatial heterogeneity that supports ecosystem diversity. These disturbances operate over time scales ranging from years to millennia.

El Niño events occasionally bring increased precipitation that triggers dramatic ecosystem responses, including widespread germination, flowering, and temporary increases in animal populations. These episodic events demonstrate the potential for rapid ecosystem change in response to altered environmental conditions.

Volcanic activity creates new substrates and alters local topography while contributing chemical inputs that influence soil chemistry and plant community composition. The frequency and intensity of volcanic disturbances vary spatially throughout the desert region.

Human Interactions and Land Use Patterns

Indigenous Cultures and Traditional Adaptations

Indigenous peoples have inhabited the Atacama Desert region for thousands of years, developing sophisticated cultural adaptations that allow survival in one of Earth's most challenging environments. Archaeological evidence suggests that human occupation has been continuous for at least 10,000 years, with complex societies developing around scarce water resources.

The Atacameño (Lican Antai) people developed advanced agricultural techniques, including terraced farming, irrigation systems, and crop varieties adapted to arid conditions and high elevations. Their traditional knowledge of water management and desert survival strategies provides valuable insights for contemporary conservation and development efforts.

The Chinchorro culture, dating back over 7,000 years, developed some of the world's earliest mummification techniques, capitalizing on the desert's natural preservation conditions. Archaeological sites throughout the region offer insights into long-term human adaptation to extreme aridity, while also highlighting the cultural significance of desert landscapes.

Mining Activities and Industrial Development

The Atacama Desert contains some of the world's largest copper, lithium, and nitrate deposits, making it a focal point for intensive mining activities that generate significant economic benefits while creating substantial environmental impacts. Large-scale copper mining operations, including some of the world's biggest open-pit mines, dominate portions of the desert landscape.

Lithium extraction from salt flats supports growing global demand for battery technology while raising concerns about water use and ecosystem impacts in areas that support unique wildlife populations. The expansion of lithium mining creates tensions between economic development and conservation goals.

Historical nitrate mining during the late 19th and early 20th centuries created boom-and-bust cycles that left lasting impacts on desert communities and landscapes. Abandoned mining towns and infrastructure demonstrate both the potential and the risks associated with resource extraction in extreme environments.

Astronomical Research and Technology Development

The Atacama Desert's exceptional atmospheric conditions, including minimal cloud cover, low humidity, and minimal light pollution, have made it a premier location for astronomical research facilities. Major observatories, including ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter Array) and numerous optical telescopes, take advantage of the region's pristine skies.

Space research programs utilize the desert as an analogue for Mars exploration, testing equipment and techniques under conditions that simulate extraterrestrial environments. These research activities contribute to scientific knowledge while raising awareness about the desert's unique characteristics and conservation value.

The concentration of astronomical facilities requires careful coordination to minimize impacts on desert ecosystems while maximizing scientific benefits. Dark sky protection efforts help maintain the pristine conditions necessary for astronomical research while supporting conservation goals.

Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Challenges

Projected Environmental Changes

Climate change projections for the Atacama Desert suggest complex patterns of environmental change that may include altered precipitation patterns, temperature increases, and changes in fog frequency and intensity. These changes could significantly affect the limited ecosystems that depend on current climate conditions.

Rising temperatures may increase evaporation rates and alter the thermal dynamics that drive fog formation along the coast. Changes in fog patterns could have dramatic impacts on coastal ecosystems that depend on atmospheric moisture for survival.

Altered precipitation patterns, while unlikely to significantly increase overall moisture availability, could change the timing and intensity of rare rainfall events that trigger episodic ecosystem responses. These changes may impact species that are adapted to current patterns of resource availability.

Ecosystem Vulnerability and Resilience

Desert ecosystems demonstrate both high vulnerability to environmental changes and remarkable resilience through adaptations developed over millions of years of extreme conditions. Species with narrow environmental tolerances may face extinction under altered climate conditions, while others may expand their ranges.

Endemic species with limited distributions face particular risks from climate change, as their specialized adaptations may not allow survival under altered environmental conditions. Conservation strategies must account for the potential need to maintain suitable habitat conditions through active management.

Ecosystem connectivity becomes increasingly important under climate change scenarios, as species may need to track suitable habitats across the landscape. Maintaining habitat corridors and reducing fragmentation represent crucial adaptation strategies for desert conservation.

Conservation Adaptation Strategies

Adaptation strategies for Atacama Desert conservation include identifying climate refugia, maintaining habitat connectivity, and developing assisted migration programs for the most vulnerable species. These strategies require long-term planning and significant resources while addressing high levels of uncertainty about future conditions.

Ex-situ conservation programs, including seed banking and captive breeding initiatives, provide insurance against species extinctions while maintaining genetic diversity for potential future reintroduction efforts. These programs are particularly important for endemic species with limited population sizes.

Monitoring programs that track ecosystem responses to climate change provide crucial information for adaptive management strategies while building scientific understanding of desert ecosystem dynamics under changing environmental conditions.

Scientific Research and Global Significance

Astrobiology and Extremophile Research

The Atacama Desert serves as a natural laboratory for studying life under extreme conditions, with research focusing on extremophile organisms that survive in environments previously thought to be uninhabitable. These studies offer insights into the limits of life on Earth, informing the search for life on other planets.

Microbial communities within hyperarid soils demonstrate remarkable adaptations for surviving extended periods without water while maintaining metabolic activity. These organisms provide models for understanding potential life processes under Martian conditions.

Research on cryptobiotic organisms that can survive complete dehydration for extended periods contributes to an understanding of life's resilience and its potential for adaptation. These studies have applications ranging from biotechnology development to space exploration.

Ecosystem Research and Conservation Science

Long-term ecological research programs throughout the Atacama Desert examine ecosystem dynamics, species interactions, and conservation strategies under extreme environmental conditions. These studies offer crucial insights into desert ecology, providing support for evidence-based conservation planning.

Research on fog-dependent ecosystems contributes to global understanding of atmospheric water harvesting and its potential applications for water-scarce regions worldwide. These studies demonstrate the importance of atmospheric moisture sources in arid ecosystem function.

Conservation genetics research examines the evolutionary history and genetic diversity of endemic species while identifying priority populations for protection. These studies provide crucial information for conservation planning and species management in response to changing environmental conditions.

Climate and Paleoclimate Research

The Atacama Desert's exceptional preservation conditions make it a crucial location for paleoclimate research, with ancient deposits providing a record of environmental change spanning millions of years. These records contribute to an understanding of long-term climate dynamics and the responses of ecosystems.

Modern climate monitoring programs utilize the desert's stable atmospheric conditions to study global climate patterns and atmospheric processes. Research stations throughout the region contribute data to global climate monitoring networks while supporting regional environmental management.

Glacial deposits and lake sediments in high-elevation areas provide records of past precipitation patterns and ecosystem changes, informing our understanding of climate variability and ecosystem resilience under changing conditions.

Economic Significance and Sustainable Development

Resource Extraction and Economic Benefits

The Atacama Desert generates substantial economic benefits through mining activities, with copper production alone contributing billions of dollars annually to Chile's economy. These activities provide employment and government revenues while supporting infrastructure development throughout the region.

Lithium extraction for battery technology represents a rapidly growing economic sector that positions Chile as a key supplier for global clean energy transitions. The expansion of lithium production creates both opportunities and challenges for balancing economic development with environmental protection.

Tourism based on the desert's unique landscapes, astronomical facilities, and cultural heritage provides alternative economic opportunities that may be more compatible with conservation goals. Sustainable tourism development requires careful planning to minimize environmental impacts while maximizing economic benefits.

Water Resources and Management Challenges

Water scarcity poses a fundamental challenge to sustainable development throughout the Atacama Desert, as competing demands from mining, tourism, and ecosystem conservation create complex management challenges. Innovative water management strategies become crucial for balancing multiple needs.

Fog harvesting technology, inspired by natural fog capture mechanisms, provides potential solutions for supplementing water supplies while demonstrating practical applications of ecological research. These systems require ongoing development and optimization for widespread implementation.

Groundwater management becomes increasingly important as development pressures intensify, necessitating careful monitoring and regulation to prevent the overexploitation of limited aquifer resources. Sustainable extraction rates must account for extremely slow recharge rates in hyperarid environments.

Renewable Energy Potential

The Atacama Desert's exceptional solar radiation levels and consistent wind patterns create outstanding potential for renewable energy development. Solar energy projects could provide clean electricity while supporting global climate goals and regional economic development.

Large-scale solar installations require careful siting to minimize impacts on sensitive ecosystems while maximizing energy production efficiency. Environmental impact assessments must consider both direct habitat impacts and indirect effects on desert ecosystem processes.

Energy development projects can contribute to conservation funding through environmental offset programs and revenue-sharing arrangements that support the management of protected areas and research activities.

Future Prospects and Conservation Priorities

The Atacama Desert faces unprecedented challenges as global environmental changes interact with increasing development pressures and growing recognition of its scientific and conservation value. Success in balancing these competing demands will require innovative approaches that integrate conservation with sustainable economic development.

International cooperation and investment in research, conservation, and sustainable development initiatives will likely play increasingly important roles in determining the region's future. The desert's global significance for astronomy, climate research, and biodiversity conservation creates opportunities for international support and collaboration.

Technological innovations in water harvesting, renewable energy, and ecosystem monitoring provide tools for addressing conservation challenges while supporting sustainable development goals. The integration of traditional knowledge with modern technology offers particular promise for developing culturally appropriate and environmentally sound solutions.

Summary

The Atacama Desert represents one of Earth's most extraordinary and scientifically significant ecosystems, combining extreme environmental conditions with remarkable biodiversity, unique geological formations, and exceptional potential for scientific research. Covering over 105,000 square kilometers of western South America, the desert's hyperarid conditions create natural laboratories for studying life under extreme conditions while supporting endemic species found nowhere else on Earth.

The region's classification as a distinct WWF ecoregion reflects its global conservation significance and unique ecological characteristics that distinguish it from other desert systems worldwide. Protected area networks, while expanding, require continued development to ensure adequate conservation of the ecosystem's most vulnerable components and critical habitat areas.

Scientific research throughout the Atacama Desert continues to reveal new insights into extremophile biology, climate dynamics, and conservation strategies applicable to arid ecosystems worldwide. The region's role as an analogue for extraterrestrial environments makes it increasingly important for astrobiology research and space exploration programs.

Conservation challenges, including climate change, mining expansion, and increasing tourism, require coordinated responses that integrate scientific knowledge with practical management applications. The success of conservation efforts depends on collaboration between multiple stakeholders and the development of sustainable economic activities that provide incentives for ecosystem protection.

The Atacama Desert's future as a functioning ecosystem and scientific resource depends on maintaining the extreme environmental conditions and specialized communities that have evolved over millions of years. This will require balancing human activities with conservation needs while adapting to changing environmental conditions through flexible, science-based management strategies that preserve the region's essential ecological and scientific character.

The area most commonly defined as the Atacama Desert is in yellow. The outlying arid regions are in orange.