La Amistad International Park: A Sanctuary of Nature and Tradition in the Talamanca Mountains

La Amistad International Park, straddling the border between Costa Rica and Panama, is one of the most significant protected areas in the Americas. This expansive park protects one of the largest remaining areas of natural forest in Central America, located within the Cordillera de Talamanca.

La Amistad: A Transboundary Jewel in the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor

High in the cloud-shrouded peaks of the Cordillera de Talamanca, where jaguars prowl ancient forests and resplendent quetzals flash through mist-laden canopies, lies one of the most remarkable conservation achievements in the Americas. La Amistad International Park, encompassing 401,000 hectares (991,000 acres) across the Costa Rica-Panama border, represents far more than a protected area—it stands as a living symbol of international cooperation and a cornerstone of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor's mountain conservation network.

Established as the "La Amistad International Peace Park," this UNESCO World Heritage site protects one of Central America's most extensive remaining tracts of natural forest, demonstrating how transboundary conservation can transcend political boundaries to preserve a shared natural heritage. Within the broader context of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, La Amistad serves as a crucial highland refuge, connecting lowland forests with montane ecosystems and maintaining elevational migration routes essential for numerous species that are adapting to climate change.

The park's significance extends beyond its impressive size to encompass its role as a center of endemism for numerous plant and animal groups, supporting biodiversity patterns that have evolved in isolation within the Talamanca Range, Central America's highest non-volcanic mountain system. This unique position makes La Amistad essential for maintaining the genetic diversity and evolutionary processes that define Central American biodiversity.

A Vertical Sanctuary: From Lowlands to Alpine Heights

La Amistad International Park showcases one of the most complete elevational gradients found anywhere in Central America, encompassing ecosystems from lowland tropical rainforests at 200 meters (656 feet) to alpine páramo above 3,500 meters (11,483 feet). This remarkable topographical diversity creates a mosaic of eight distinct life zones, each supporting unique assemblages of species adapted to specific climatic and ecological conditions.

The park's lowland forests, extending along both Caribbean and Pacific slopes, support towering emergent trees including Ceiba pentandra and valuable timber species such as mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) and tropical cedar (Cedrela odorata). These forests transition through premontane zones characterized by increased epiphyte diversity and cooler temperatures into the spectacular cloud forests that define the Talamanca highlands.

The montane cloud forests, found between 1,500 and 3,000 meters (4,921 to 9,843 feet), represent some of the most pristine examples of this ecosystem type remaining in Central America. Here, ancient oak forests (Quercus species) create cathedral-like spaces draped with bromeliads, orchids, and ferns, while the persistent cloud cover maintains the high humidity essential for countless epiphytic species. These forests harbor extraordinary diversity, including approximately 1,000 fern species and 900 lichen species.

Above the cloud forest zone, the park's páramo ecosystems represent unique high-altitude tropical environments where specialized plants such as Puya dasylirioides and various Hypericum species have adapted to extreme conditions of intense solar radiation, freezing temperatures, and high winds. These alpine zones, dotted with glacial lakes and cold marshes, support endemic species found nowhere else on Earth.

Biodiversity Hotspot of the Talamancas

La Amistad International Park harbors one of Central America's most spectacular concentrations of biodiversity, with more than 10,000 flowering plant species described within the park, along with 215 mammal species, approximately 250 reptile and amphibian species, and 115 species of freshwater fish. This remarkable diversity reflects the park's position at the convergence of the North American and South American biogeographic zones, as well as its extensive elevational gradients.

The park's avian diversity approaches 500 species, making it one of the premier birding destinations in Central America. Among the most spectacular residents, the resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) finds ideal habitat in the cloud forests, while the three-wattled bellbird (Procnias tricarunculatus) and bare-necked umbrellabird (Cephalopterus glabricollis) represent examples of the distinctive high-elevation fauna. Endemic species include the black-faced solitaire (Myadestes melanops) and the Zeledonia (Zeledonia coronata), a monotypic genus found only in the highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama.

The park supports Central America's most complete assemblage of large mammals, including five species of big cats: pumas (Puma concolor), ocelots (Leopardus pardalis), margay (Leopardus wiedii), jaguars (Panthera onca), and jaguarundis (Herpailurus yagouaroundi). The endangered Baird's tapir (Tapirus bairdii) finds crucial refuge in the park's extensive forests, while researchers have documented the possible presence of an undescribed tapir subspecies near the Panama border, highlighting the region's potential for new scientific discoveries.

The park's amphibian diversity reflects its position as a center of endemism within the Cordillera de Talamanca. At least seven amphibian species are endemic to the Cordillera, including the splendid poison frog, Chiriquí fire salamander (Bolitoglossa cathyledecae), and Cordillera Talamanca salamander (Bolitoglossa sooyorum). These endemic species demonstrate the evolutionary significance of the Talamanca highlands as isolated centers of speciation.

Transboundary Conservation: A Model of International Cooperation

La Amistad International Park exemplifies the vision of transboundary conservation that underpins the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, demonstrating how international cooperation can achieve conservation goals that transcend political boundaries. The park spans four Costa Rican provinces (San José, Cartago, Limón, and Puntarenas) and two Panamanian provinces (Bocas del Toro and Chiriquí), necessitating coordinated management between two national governments with distinct legal systems, administrative structures, and conservation priorities.

This transboundary approach is further strengthened by the establishment of complementary La Amistad Biosphere Reserves on both sides of the border. The Costa Rican La Amistad Biosphere Reserve encompasses the park's foothills and mountainous areas, forming part of the larger Cordillera de Talamanca and supporting eight of Costa Rica's twenty life zones. The reserve's diverse topography extends from lowland tropical rainforests to high-altitude cloud and páramo forests above 3,000 meters (9,843 feet), with Mount Kamuk exemplifying the region's ecological richness.

The Panamanian La Amistad Biosphere Reserve extends from the Caribbean coast to the highlands of the Cordillera de Talamanca, encompassing a diverse range of habitats, including mangrove forests, lowland rainforests, and high-altitude cloud forests. The reserve also includes lagoons recognized under the Ramsar Convention for their importance to migratory bird species, while Volcán Barú, Panama's only volcano, adds geological diversity to the protected landscape.

This dual biosphere reserve system proves essential for protecting wide-ranging species such as jaguars and tapirs, whose territories often span both sides of the border. Joint patrol programs, coordinated research initiatives, and shared management protocols ensure that conservation efforts remain effective across the entire ecosystem. The success of this cooperation has influenced transboundary conservation efforts throughout the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor and serves as a model for similar initiatives worldwide.

Within the broader context of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, La Amistad serves multiple critical functions. The park provides highland refuge areas that may become increasingly important as climate change forces species to seek cooler conditions at higher elevations. The extensive elevational gradients within the park create natural migration corridors that allow species to track suitable climate conditions as temperatures change.

The park's position linking the extensive lowland forests of the Caribbean slope with the fragmented Pacific coast forests makes it essential for maintaining connectivity across Central America's complex topography. This connectivity becomes increasingly crucial as lowland areas experience greater development pressure and habitat fragmentation.

Indigenous Heritage and Cultural Landscapes

La Amistad International Park encompasses not only extraordinary natural diversity but also remarkable cultural heritage, protecting the ancestral territories of multiple Indigenous groups whose traditional knowledge systems have contributed to the region's biodiversity conservation for millennia. Four Indigenous tribes currently reside within the mountains: the Bribri, Ngobe-Bugle, Boruca, and Naso, each maintaining distinct languages, cultural practices, and relationships with the forest ecosystems.

The Bribri and Cabécar peoples of Costa Rica have developed a sophisticated understanding of cloud forest ecology, including the traditional management of cacao (Theobroma cacao) under the forest canopy and the sustainable harvesting of medicinal plants. Their traditional agricultural systems, based on small-scale polyculture and forest management, demonstrate how human communities can integrate with rather than dominate complex forest ecosystems.

On the Panamanian side, the Ngöbe, Teribe, and Buglé communities continue to practice traditional agriculture, hunting, and fishing, while maintaining spiritual connections to the land that recognize the forest as a living entity deserving respect and careful stewardship. These Indigenous worldviews offer valuable perspectives on conservation that complement scientific approaches, emphasizing the importance of long-term sustainability.

Indigenous reserves within the park's buffer zones serve as crucial components of the overall conservation strategy, demonstrating how traditional land management practices can contribute to biodiversity preservation. The integration of Indigenous knowledge with modern conservation science has become increasingly important as protected area managers recognize the value of traditional ecological knowledge in understanding ecosystem dynamics and developing sustainable management practices.

Scientific Frontiers in an Unexplored Wilderness

Despite its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site and its importance for regional conservation, much of La Amistad International Park remains scientifically unexplored, presenting extraordinary opportunities for biodiversity discovery and ecological research. According to research projects, the park is home to approximately 7,500 plant species, 17,000 beetle species, and 380 herpetological collections. However, vast areas remain unstudied due to challenging terrain and limited access.

Scientific expeditions conducted by institutions such as the Natural History Museum of London, Costa Rica's National Institute of Biodiversity (INBio), and the University of Panama have provided valuable insights into the park's biodiversity; however, significant portions remain largely uncharted. This unexplored status suggests enormous potential for discovering new species, particularly among invertebrate groups and microorganisms adapted to the park's unique high-elevation environments.

Recent technological advances, including environmental DNA sampling, acoustic monitoring, and remote sensing technologies, offer new possibilities for documenting biodiversity in remote areas without requiring extensive physical access. These approaches may reveal previously unknown patterns of species distribution and ecosystem functioning within the park's pristine environments.

Long-term research programs within the park contribute to our understanding of cloud forest ecology, the impacts of climate change on montane ecosystems, and the conservation biology of threatened species. Studies of altitudinal migration patterns, phenological responses to climate change, and ecosystem service provision provide essential information for adaptive management approaches.

Conservation Challenges in a Changing World

Despite its protected status and remote location, La Amistad International Park faces mounting pressures that reflect broader challenges confronting mountain ecosystems in Central America. Climate change presents perhaps the most significant long-term threat, as rising temperatures may shift optimal habitat conditions beyond current park boundaries and alter the precipitation patterns essential for cloud forest ecosystems.

The park's cloud forests depend on specific climatic conditions that maintain persistent fog and moderate temperatures. Changes in precipitation patterns or temperature regimes could fundamentally alter these ecosystems, potentially affecting the countless species that depend on constant high humidity. Monitoring programs document changes in cloud formation patterns and their potential impacts on endemic species adapted to these unique conditions.

Illegal activities, including logging, hunting, and drug trafficking, present ongoing enforcement challenges in the park's remote areas. The rugged terrain that helps protect the park's ecosystems also complicates patrol efforts and monitoring activities. Addressing these challenges requires enhanced cooperation between Costa Rican and Panamanian authorities, improved funding for park management, and community-based conservation initiatives that provide economic alternatives to illegal activities.

Development pressures in surrounding areas threaten to isolate the park from other protected areas, potentially disrupting migration routes and genetic exchange, which are essential for the long-term viability of the species. Maintaining connectivity with other components of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor requires coordinated land-use planning that extends well beyond park boundaries.

Economic Dimensions and Sustainable Development

La Amistad International Park demonstrates significant potential for sustainable economic development through carefully managed ecotourism, research activities, and the provision of ecosystem services. The park's pristine environments and extraordinary biodiversity attract researchers, students, and nature enthusiasts from around the world, generating income for local communities while supporting conservation objectives.

The park's vast forests provide crucial ecosystem services, including carbon storage, watershed protection, and climate regulation, that benefit both local and global communities. These forests store enormous quantities of carbon that, if released through deforestation, would contribute significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon credit programs may provide additional financial incentives for forest conservation while contributing to climate change mitigation efforts.

Sustainable harvesting of non-timber forest products, including medicinal plants, fruits, and handicraft materials, provides income opportunities for Indigenous communities while maintaining forest cover. These activities demonstrate the economic value of intact ecosystems and create incentives for long-term conservation.

The park's role in watershed protection provides essential services for both countries, maintaining water quality and quantity for downstream communities and agricultural areas. The economic value of these services far exceeds the costs of park management and protection, providing strong economic justification for conservation investment.

A Vision for Transboundary Conservation

La Amistad International Park represents more than an impressive protected area; it embodies a vision of conservation that transcends political boundaries and integrates the protection of both natural and cultural heritage. Its success demonstrates how international cooperation can achieve conservation goals impossible for individual nations working alone, while its role within the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor showcases the importance of landscape-scale thinking in biodiversity conservation.

The park's extensive unexplored areas hold enormous potential for scientific discovery and contribute to our understanding of tropical montane ecosystems and their responses to environmental change. As one of Central America's last great wildernesses, the park serves as both a refuge for species threatened by habitat loss and a natural laboratory for studying ecosystem processes in pristine environments.

From the misty peaks where páramo plants cling to volcanic soils to the lowland forests where jaguars follow ancient trails, La Amistad International Park continues to demonstrate that effective conservation requires recognizing the interconnectedness of natural and human systems across landscapes and political boundaries. The park's success depends on continued international cooperation, Indigenous community engagement, and recognition that biodiversity conservation represents one of the most important investments we can make in our shared future.

In the calls of endemic birds echoing through cloud forests and the traditional knowledge of Indigenous communities, in the pristine watersheds and unexplored valleys, La Amistad International Park stands as a testament to what can be achieved when nations work together to protect their shared natural heritage, serving as a beacon of hope for transboundary conservation throughout the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor and beyond.

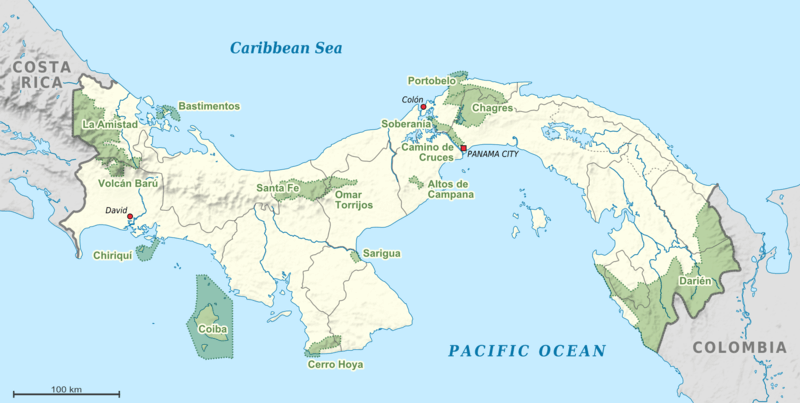

Map depicting the location of the National Parks of Panama.