Río Bravo del Norte: The Great River That Unites and Divides Two Nations

In Colorado's San Juan Mountains, where streams form from melting snow, begins a vital North American waterway. Known as the Rio Grande in the U.S. and Río Bravo del Norte in Mexico, it stretches from alpine tundra to tropical delta, acting as the boundary between the two nations.

From Colorado's Peaks to the Gulf: The Binational Journey of the Río Bravo/Rio Grande

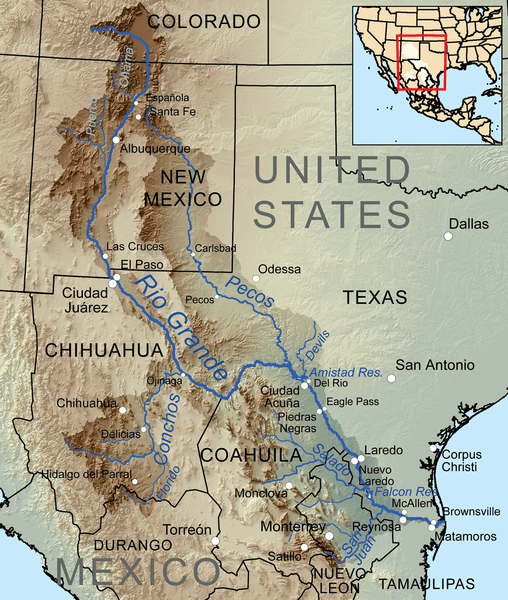

In the high peaks of Colorado's San Juan Mountains, where crystalline streams gather force from melting snowfields, begins one of North America's most culturally and politically significant waterways. Known as the Rio Grande in the United States and Río Bravo del Norte in Mexico, this continental river spans 3,051 kilometers (1,896 miles) as it carves its path from alpine tundra to tropical delta, ultimately serving as the liquid frontier between two nations for over 2,000 kilometers (1,254 miles) of its journey.

For Mexico, the Río Bravo represents far more than a geographic boundary—it embodies centuries of cultural identity, economic development, and environmental adaptation in some of North America's most challenging landscapes. From the sprawling industrial metropolis of Ciudad Juárez to the fertile agricultural valleys of Tamaulipas, the Mexican side of this great river tells a story of resilience, innovation, and the complex relationship between human ambition and natural limits in the arid borderlands.

The Mexican Watershed: Río Bravo's Southern Domain

While the Río Bravo originates in United States territory, its character and ultimate destiny are profoundly shaped by Mexican landscapes and tributaries. The river's most significant tributary, the Río Conchos, flows entirely within Mexico, originating in the Sierra Madre Occidental of Chihuahua and contributing more water to the main stem than any tributary from the north. This 560-kilometer (350-mile) Mexican river drains over 67,000 square kilometers (26,000 square miles) of the Chihuahuan Desert, making it the hydrological lifeline that sustains the Río Bravo through its most arid reaches.

The Conchos River system illustrates the remarkable adaptation of Mexican communities to desert hydrology. Towns like Ojinaga, Chihuahua, have thrived for centuries at the confluence of these rivers, developing sophisticated irrigation systems that support agriculture in regions receiving less than 250 millimeters (10 inches) of annual rainfall. These settlements represent continuities of Indigenous technological knowledge, Spanish colonial engineering, and modern hydraulic management that span over 400 years of continuous occupation.

Beyond the Conchos, numerous smaller Mexican tributaries contribute to the Río Bravo's flow, including the Río San Rodrigo, Río Escondido, and Río Salado. These waterways drain the complex geography of northern Mexico, from the pine-oak forests of the Sierra Madre Oriental to the creosote flats of the Chihuahuan Desert. Each contributes not merely water, but sediments, nutrients, and biological diversity that shape the river's ecological character throughout its international reach.

The Chihuahuan Desert: Mexico's Vast Northern Frontier

The Río Bravo's journey through Mexico traverses the heart of the Chihuahuan Desert, North America's largest hot desert, which extends across over 500,000 square kilometers (193,000 square miles) of northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. This vast ecoregion, characterized by dramatic mountain ranges separated by broad basins, creates the environmental context within which Mexican communities along the Río Bravo have developed their distinctive cultures and economies.

The desert's remarkable biodiversity includes over 3,000 plant species, many of which are endemic to the region, resulting in landscapes of extraordinary beauty and ecological complexity. Iconic species such as the Chihuahuan Desert's lechuguilla agave (Agave lechuguilla), ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens), and various barrel cacti (Ferocactus spp.) dominate vast areas, while riparian corridors along the Río Bravo support islands of mesquite (Prosopis spp.) and Mexican buckeye (Ungnadia speciosa) that provide critical habitat for wildlife and resources for human communities.

Mexican settlements throughout the Chihuahuan Desert have developed remarkable strategies for thriving in this water-limited environment. Traditional architecture featuring thick adobe walls, courtyards designed to capture and channel scarce rainfall, and underground storage systems reflects centuries of accumulated knowledge about living sustainably in arid lands. These techniques, refined over generations, offer important lessons for contemporary water and energy conservation efforts.

Mexican Cities of the Río Bravo: Urban Oases and Industrial Powerhouses

The Mexican side of the Río Bravo corridor supports some of the country's most dynamic urban centers, each representing different aspects of Mexico's economic and cultural evolution. Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, stands as the largest Mexican city along the river, with a metropolitan population exceeding 1.5 million inhabitants. This sprawling industrial center has emerged as one of North America's most significant manufacturing hubs, hosting hundreds of maquiladora factories that produce a wide range of products, including automotive components and consumer electronics, for global markets.

Ciudad Juárez's relationship with the Río Bravo illustrates both the opportunities and challenges of rapid urban growth in water-scarce environments. The city's location at the confluence of the Río Bravo and Río Conchos provided the hydrological foundation for settlement, but modern industrial and residential demands far exceed natural water supplies. Sophisticated groundwater management systems, water recycling facilities, and cross-border cooperation with El Paso, Texas, represent innovative approaches to urban sustainability in desert environments.

Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, serves as Mexico's busiest inland port and a crucial link in North American trade networks. Located along the Río Bravo opposite Laredo, Texas, this city of over 400,000 inhabitants processes billions of dollars in commercial goods annually, making it a cornerstone of Mexico's export economy. The city's growth reflects the Río Bravo's role not as a barrier, but as an axis of economic integration between Mexico and its northern neighbors.

Reynosa and Matamoros, both in Tamaulipas, represent the Río Bravo's lower reach, where the river transitions from desert waterway to subtropical delta system. These cities, with combined populations exceeding 1.2 million, anchor Mexico's Gulf Coast economy while maintaining deep cultural connections to the river's ecological rhythms. Traditional festivals, cuisine, and agricultural practices in these communities reflect centuries of adaptation to the river's seasonal flooding patterns and the rich biodiversity of its lower watershed.

Map depicting the Rio Grande/Río Bravo del Norte and its tributaries within its drainage basin.

Agricultural Landscapes: Mexico's Río Bravo Valleys

The fertile valleys of the Mexican Río Bravo support some of Mexico's most productive agricultural regions, creating green corridors through otherwise arid landscapes. The Juárez Valley in Chihuahua, irrigated by waters from both the Río Bravo and Río Conchos, produces cotton, alfalfa, pecans, and chilies that supply both domestic and international markets. This 50,000-hectare (123,000-acre) agricultural zone demonstrates the transformation possible when desert soils receive reliable water supplies.

Mexican agricultural communities along the Río Bravo have developed distinctive crop varieties adapted to local conditions. The famous Hatch-type New Mexico chiles, while associated with the United States, actually represent genetic material that flows freely across the border, with many varieties originating from Mexican seed stocks developed over centuries of selection. Similarly, southwestern cotton varieties, pecans, and other crops reflect the binational agricultural heritage of the Río Bravo watershed.

The Tamaulipas portion of the Río Bravo valley supports Mexico's most northeastern agricultural region, where irrigation systems dating to the colonial period continue to channel river waters across thousands of hectares. This region produces citrus fruits, sugarcane, corn, and sorghum, benefiting from the subtropical climate and fertile alluvial soils deposited by centuries of river flooding. However, like agricultural systems throughout the watershed, these operations face mounting challenges from water scarcity, climate variability, and competition from urban and industrial users.

Indigenous Heritage and Colonial Legacies

Long before European contact, numerous Indigenous groups inhabited the landscapes along the Río Bravo, developing sophisticated knowledge systems to survive and thrive in the region's challenging environments. The Jumano people, who occupied much of the Río Conchos and middle Río Bravo region, maintained extensive trade networks that connected the Gulf of Mexico with the American Southwest, using the river system as a transportation corridor and source of resources.

The Coahuiltecan peoples of the lower Río Bravo developed remarkable adaptations to the river's variable flows and seasonal resources. Their detailed knowledge of edible plants, seasonal hunting patterns, and water sources enabled sustainable populations in landscapes that challenged later European settlers. Archaeological evidence suggests that these communities managed controlled burning regimes, which maintained grasslands and encouraged wildlife populations along the river corridors.

Spanish colonization, beginning in the 16th century, introduced new technologies, crops, and land use patterns that fundamentally transformed the Río Bravo watershed. The establishment of missions, presidios, and civilian settlements created nodes of intensive agriculture and European-style animal husbandry that required substantial water resources. The acequia irrigation systems introduced during this period, based on Moorish engineering principles refined over centuries in Iberia, enabled agricultural expansion into previously uncultivated areas.

Mexican independence in 1821 and the subsequent Texas Revolution, Mexican-American War, and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) established the Río Bravo as an international boundary, fundamentally altering its political and economic significance. For Mexico, the loss of vast territories north of the river represented a profound geographical and cultural trauma, while the establishment of the river boundary created new challenges and opportunities for border communities.

The Maquiladora Revolution and Industrial Transformation

Beginning in the 1960s, Mexico's Border Industrialization Program transformed the Río Bravo corridor into one of North America's most important manufacturing regions. The maquiladora system, which allows foreign companies to import materials duty-free for assembly in Mexico before export, created hundreds of thousands of jobs in cities like Ciudad Juárez, Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, and Matamoros.

This industrial transformation dramatically altered water demand patterns along the Mexican side of the Río Bravo. Manufacturing processes requiring substantial water inputs, combined with rapidly growing urban populations attracted by employment opportunities, have strained water supplies throughout the region. Mexican authorities developed innovative water management strategies, including groundwater mining, water recycling systems, and negotiations for increased allocations from the Río Bravo's flow.

The environmental consequences of rapid industrialization have created complex challenges for Mexican communities along the river. Air and water quality concerns, hazardous waste management issues, and pressure on natural ecosystems represent the costs of economic development in water-scarce environments. However, newer generations of maquiladora operations increasingly emphasize environmental stewardship and resource efficiency, reflecting both regulatory requirements and corporate sustainability commitments.

Binational Water Management: The Mexican Perspective

Mexico's relationship with Río Bravo waters operates within complex legal and diplomatic frameworks established by treaties with the United States. The 1944 Water Treaty, which governs the allocation of waters from the Río Bravo and Colorado River, reflects negotiations conducted during a period of above-average rainfall and more modest development pressures than exist today.

From the Mexican perspective, the treaty's provisions create both opportunities and constraints for national development. Mexico receives guaranteed allocations of Río Bravo waters but must also deliver specific quantities of water to the United States from Mexican tributaries, particularly the Río Conchos. During drought periods, these obligations can strain Mexican water supplies and create tensions between international commitments and domestic needs.

The Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas (CILA), Mexico's counterpart to the U.S. International Boundary and Water Commission, manages Mexican participation in binational water administration. This agency oversees reservoir operations, water quality monitoring, flood control measures, and boundary demarcation along the Río Bravo, requiring constant coordination with U.S. counterparts while advocating for Mexican interests.

Recent drought periods have highlighted the challenges of managing shared water resources under increasingly stressed conditions. Mexican reservoir levels in the Río Conchos basin have fallen to critical levels, forcing difficult decisions about water allocation between agricultural users, urban supplies, and international treaty obligations. These situations illustrate the complex tradeoffs inherent in managing finite water resources among competing demands.

Mexican Environmental Conservation Efforts

Despite facing enormous development pressures, Mexico has established significant protected areas and conservation programs along the Río Bravo watershed. The Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Maderas del Carmen in Coahuila protects over 208,000 hectares (514,000 acres) of Chihuahuan Desert ecosystems, including critical watershed areas that contribute to Río Bravo tributaries.

Mexican conservation efforts often emphasize community-based approaches that integrate environmental protection with local economic development. Ejidos (communal land holdings) throughout the Río Bravo watershed participate in payment for ecosystem services programs, sustainable forestry initiatives, and ecotourism projects that provide income while protecting natural resources. These approaches reflect Mexico's constitutional commitment to environmental stewardship and the recognition that conservation efforts must address the economic needs of rural communities.

Binational conservation partnerships between Mexican and U.S. agencies have achieved significant successes in protecting shared ecosystems along the Río Bravo. The Big Bend region, where the river creates dramatic canyons between Texas and Chihuahua, benefits from coordinated management between Big Bend National Park and Mexican protected areas. These partnerships address challenges such as wildlife migration, fire management, and invasive species control that transcend national boundaries.

Cultural Identity and the Río Bravo

For Mexican communities along the Río Bravo, the river represents far more than a water source or political boundary—it embodies cultural identity and historical continuity that spans centuries. Traditional festivals, cuisine, music, and artistic expressions throughout the region reflect deep connections to the river's seasonal rhythms and ecological abundance.

The norteño musical tradition, which originated in the borderlands of northeastern Mexico, draws inspiration from the landscapes and experiences of Río Bravo communities. Songs celebrating the river, the desert, and the resilience of border peoples have become emblematic of Mexican regional culture, spreading throughout Mexico and Mexican-American communities in the United States.

Culinary traditions along the Mexican Río Bravo showcase the creative adaptation of Indigenous ingredients and techniques to the opportunities provided by river valley agriculture. Dishes featuring river fish, desert plants, and agricultural products from irrigated valleys represent unique regional cuisines that differ significantly from Mexico's better-known culinary traditions. The use of native chiles, quelites (wild greens), and other local ingredients creates flavors and preparations found nowhere else in Mexico.

Challenges and Opportunities in the 21st Century

Climate change poses unprecedented challenges for Mexican communities along the Río Bravo, with projections indicating continued warming, increased evaporation rates, and potentially reduced precipitation in critical watershed areas. These changes threaten not only water supplies but also the cultural and economic systems that have evolved around the river's historical patterns.

However, Mexico's experience managing water resources in arid environments provides valuable knowledge for adaptation strategies. Traditional water harvesting techniques, drought-resistant crop varieties, and community-based resource management systems, developed over centuries, offer potential solutions to contemporary challenges. Additionally, Mexico's growing renewable energy sector, particularly solar power development in the northern desert regions, could reduce pressure on water resources currently used for energy production.

The continued growth of Mexico's border economy presents both opportunities and challenges for sustainable development along the Río Bravo. Advanced manufacturing operations increasingly emphasize resource efficiency and environmental stewardship, while growing urban populations demand improved water and wastewater infrastructure. Balancing economic development with environmental sustainability will require innovative approaches to urban planning, industrial ecology, and regional cooperation.

Conclusion: The Río Bravo as Mexico's Northern Lifeline

The Río Bravo del Norte stands as one of Mexico's most significant geographical features, shaping the nation's northern frontier and connecting it to broader continental systems. From its role in pre-Columbian trade networks to its function as a modern industrial corridor, the river has continuously adapted to serve the changing needs of Mexican society while maintaining its fundamental importance as a source of life in the desert.

For contemporary Mexico, the Río Bravo represents both heritage and future—a connection to Indigenous and colonial pasts as well as a foundation for 21st-century development. The river's management will require balancing respect for cultural traditions with adaptation to new environmental and economic realities, maintaining the delicate equilibrium between human needs and ecological sustainability that has characterized successful desert civilizations throughout history.

As Mexico continues to develop its northern regions and deepen its integration with North American markets, the Río Bravo will remain central to these efforts. The river's future depends on Mexico's ability to combine traditional knowledge with modern technology, community wisdom with scientific understanding, and national development with international cooperation. In meeting these challenges, Mexico's experience along the Río Bravo may offer valuable insights for sustainable development in arid regions worldwide, demonstrating that prosperity and environmental stewardship can coexist and flourish together, even in the planet's most challenging environments.