Hispaniola: A Caribbean Crucible of History, Culture, and Biodiversity

Nestled within the Greater Antilles, Hispaniola is a testament to the region's complex history, rich cultural tapestry, and extraordinary biodiversity. As the second-largest island in the Caribbean, Hispaniola encompasses a world of contrasts, from towering mountains to lush forests and sun-drenched beaches.

Peaks, Plains, and Revolutions: Understanding Hispaniola's Complex Tapestry

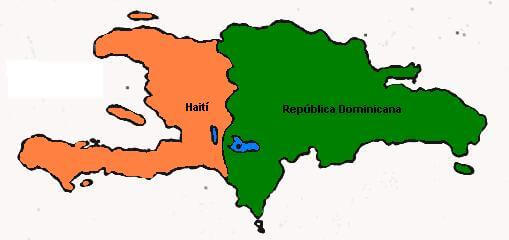

Nestled in the heart of the Caribbean, the island of Hispaniola is a testament to the region's complex history, rich cultural tapestry, and extraordinary biodiversity. As the second-largest island in the Caribbean Sea, Hispaniola's 76,192 square kilometers (29,418 square miles) encompass a world of contrasts, from towering mountain peaks to lush tropical forests and sun-drenched beaches. This remarkable landmass, divided between two sovereign nations - Haiti to the west and the Dominican Republic to the east - offers a unique lens to explore the enduring impacts of colonialism, revolution, and nation-building in the Americas.

Geographical Context and Topography

Hispaniola's strategic location within the Greater Antilles archipelago has played a pivotal role in shaping its history and development. Situated approximately 80 kilometers (50 miles) southeast of Cuba, 190 kilometers (118 miles) west of Puerto Rico, and 130 kilometers (80 miles) east of Jamaica, the island has long been a crossroads of Caribbean commerce and cultural exchange.

Three major mountain ranges dominate the island's topography, each contributing to Hispaniola's diverse landscapes and microclimates:

1. Cordillera Central: Stretching across Haiti and the Dominican Republic, this impressive range forms the island's backbone. It boasts the highest peak in the Caribbean, Pico Duarte, which soars to 3,098 meters (10,164 feet) above sea level. The Cordillera Central plays a crucial role in the island's hydrology, giving rise to numerous rivers and creating distinct ecological zones.

2. Cordillera Septentrional: Running parallel to the Cordillera Central along the northern coast of the Dominican Republic, this range extends into the Atlantic Ocean, forming the picturesque Samaná Peninsula. Its highest point, Loma Alto de la Bandera, reaches 2,277 meters (7,469 feet).

3. Sierra de Bahoruco: Originating in the southwestern Dominican Republic, this range continues into Haiti as the Massif de la Selle and Massif de la Hotte. These mountains form the rugged spine of Haiti's southern peninsula and are home to some of the island's most unique and endangered ecosystems.

Between these mountain ranges lie fertile valleys and coastal plains that have historically been the centers of agriculture and human settlement. For instance, the Cibao Valley in the Dominican Republic is renowned for its tobacco production, while the Artibonite Valley in Haiti is crucial for rice cultivation.

Hispaniola topographic map.

Climate and Ecosystems

Hispaniola's varied topography gives rise to a remarkable diversity of climatic conditions. The island experiences a tropical maritime climate moderated by the surrounding Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. However, local conditions can vary dramatically over short distances due to the influence of mountain ranges and prevailing winds.

The northeast trade winds play a significant role in shaping the island's climate, depositing moisture on the northern slopes of the mountains and creating rain shadow effects on the southern coasts. This phenomenon results in stark contrasts between lush, tropical areas and more arid regions.

Lowland areas typically experience hot and humid conditions, with average temperatures around 28°C (82°F). In contrast, higher elevations enjoy cooler temperatures, with some of the highest peaks even experiencing occasional frost during the dry season.

This climatic diversity supports four distinct ecoregions:

1. Hispaniolan moist forests: These forests cover approximately 50% of the island and dominate the northern and eastern portions, extending from the lowlands to 2,100 meters (6,900 feet) in elevation. They are characterized by high biodiversity and include species such as the West Indian mahogany and the royal palm.

2. Hispaniolan dry forests: These forests occupy about 20% of the island and are found in the rain shadows of the mountains, particularly in the southern and western portions of the island and the Cibao Valley. They are home to drought-resistant species like ceiba and gumbo-limbo trees.

3. Hispaniolan pine forests: These forests cover about 15% of the island and are found above 850 meters (2,790 feet) in elevation. They are dominated by the Hispaniolan pine (Pinus occidentalis), an endemic species crucial to the island's ecology.

4. Greater Antilles mangroves: These coastal ecosystems surround a chain of lakes and lagoons in the south-central region of the island. They play a vital role in coastal protection and serve as nurseries for many marine species.

Historical Overview

The story of Hispaniola is one of dramatic transformations, cultural encounters, and resilience in the face of adversity. The island's recorded history begins with the Taíno people, who migrated from South America around 1200 CE. The Taíno developed a sophisticated culture with a complex social structure, religious beliefs, and agricultural practices.

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked a turning point in the island's history. Columbus named the island La Isla Española, which later became Hispaniola in its Anglicized form. The Spanish quickly established settlements, including La Navidad (the first European settlement in the Americas) and later Santo Domingo, which became the capital of their expanding colonial empire.

The impact of European colonization on the indigenous population was devastating. Harsh enslavement practices, disease, and the redirection of resources led to a catastrophic decline in the Taíno population. From an estimated 400,000 in 1508, their numbers plummeted to a mere 26,000 by 1514.

As Spain's attention shifted to conquests on the American mainland, Hispaniola became a haven for pirates from various European nations. The 17th century saw the French gain a foothold on the western part of the island, leading to the formal division of Hispaniola in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick.

The French colony of Saint-Domingue, established in the western third of the island, became incredibly prosperous through its sugar plantations and slave labor. Known as the "Pearl of the Antilles," it was one of the wealthiest colonies in the world. However, this prosperity came at a terrible human cost, with hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans subjected to brutal conditions.

The late 18th century saw the eruption of one of the most significant slave revolts in history. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) not only led to the abolition of slavery but also resulted in the establishment of Haiti as the world's first Black republic. This momentous event sent shockwaves throughout the Americas and had profound implications for the institution of slavery worldwide.

The eastern part of the island, which remained under Spanish and later French control, eventually gained independence as the Dominican Republic in 1844. Since then, the two nations have followed divergent paths, shaped by their unique historical experiences, political developments, and economic challenges.

La Española

Biodiversity and Conservation

Hispaniola's diverse ecosystems support an impressive array of flora and fauna, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth. The island is home to over 300 species of birds, including 31 endemic species. Notable among these are the Hispaniolan trogon, the Hispaniolan parakeet, and the endangered Ridgway's hawk.

While the island's mammalian fauna is less diverse, it includes several unique species. The Hispaniolan solenodon and the Hispaniolan hutia are endemic mammals that have survived since prehistoric times. Both are considered living fossils and are critically endangered.

Hispaniola's herpetofauna is particularly rich, with over 170 species of reptiles and amphibians, many of which are endemic. The Rhinoceros iguana and the Tiburon stream frog are just two examples of the island's unique reptile and amphibian species.

However, this extraordinary biodiversity faces significant threats from habitat destruction, climate change, and invasive species. Deforestation has been a particularly pressing issue, especially in Haiti, where the demand for charcoal has led to extensive forest cover loss. In recent years, the Dominican Republic has made strides in increasing its forest cover, highlighting the different approaches to environmental management between the two nations.

Conservation efforts on the island face numerous challenges, including limited resources, political instability, and competing economic priorities. Nevertheless, ongoing initiatives to protect critical habitats and species, such as establishing national parks and protected areas in both countries, are underway.

Economic and Social Landscape

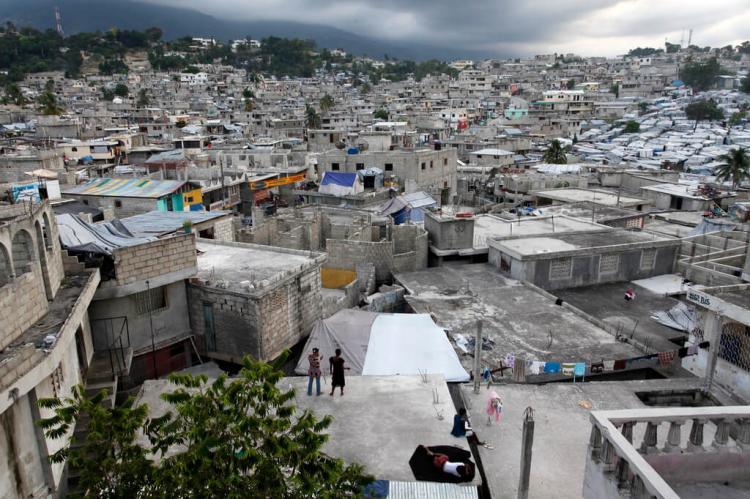

The economic trajectories of Haiti and the Dominican Republic have diverged significantly since their respective independences. Haiti, burdened by high reparations demanded by France following its revolution and subject to frequent political upheavals, has struggled with persistent poverty and underdevelopment. The country faces numerous challenges, including limited access to education, healthcare, and basic infrastructure.

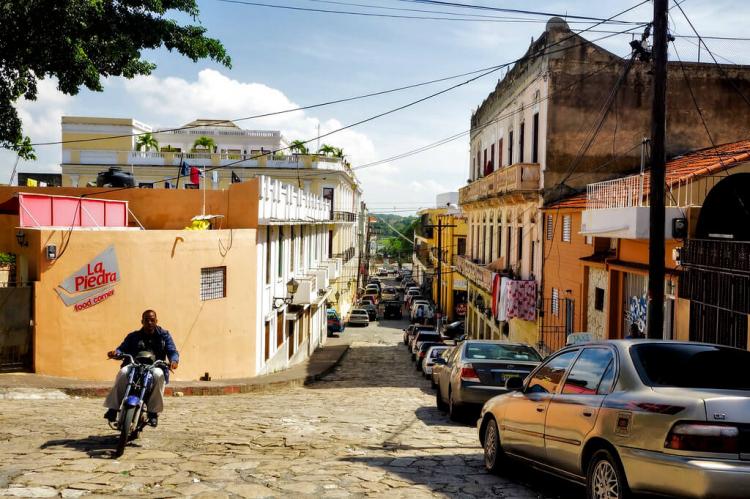

The Dominican Republic, on the other hand, has developed into one of the largest economies in the Caribbean. Its diversified economy has strong tourism, manufacturing, and services sectors. The country has also made significant strides in education and healthcare, although disparities remain, particularly in rural areas.

Agriculture is vital in both countries' economies, albeit to differing degrees. Cash crops such as sugarcane, coffee, and cacao are important exports in the Dominican Republic. The country has also developed a significant tobacco industry centered in the Cibao Valley. Haiti's agricultural sector, while less developed, remains crucial for subsistence and local markets. Rice cultivation in the Artibonite Valley is particularly important.

Tourism is a significant economic driver in the Dominican Republic, with its beaches, colonial architecture, and natural attractions drawing millions of visitors annually. Haiti's tourism sector, while less developed, has potential for growth, particularly in niche markets such as cultural and eco-tourism.

Cultural Tapestry

Hispaniola's cultural landscape is as diverse as its natural environment, reflecting the island's complex history of indigenous, African, and European influences. This cultural richness is evident in the languages, religions, music, and traditions of both nations.

Spanish is the official language in the Dominican Republic, and Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion. However, African and indigenous influences are evident in many aspects of Dominican culture, from the syncretic religious practices of folk Catholicism to the rhythms of merengue music.

Haiti's revolutionary history and African heritage strongly influence its cultural identity. While French is the language of government and education, Haitian Creole is spoken by the entire population. Religiously, Haiti presents a unique blend of Roman Catholicism and Vodou, a syncretic religion with West African roots.

Music and dance play central roles in the cultures of both nations. The merengue and bachata of the Dominican Republic and the kompa and rara of Haiti are not just forms of entertainment but expressions of national identity and historical memory.

Contemporary Challenges and Future Prospects

As Hispaniola enters the 21st century, Haiti and the Dominican Republic face various challenges and opportunities. Climate change poses a significant threat to the island, with rising sea levels, increased hurricane intensity, and changing rainfall patterns potentially impacting agriculture, tourism, and coastal communities.

Environmental degradation, particularly deforestation and soil erosion, remains a pressing concern, especially in Haiti. Addressing these issues will require sustained effort, international cooperation, and innovative approaches to sustainable development.

Political stability and good governance continue to be challenged, particularly in Haiti, where frequent political crises have hampered economic development and social progress. The Dominican Republic, while more stable, faces its own political challenges, including corruption and social inequality.

Despite these challenges, there are reasons for optimism. Both countries have young, dynamic populations with the potential to drive innovation and change. Initiatives to improve education, expand access to technology, and promote sustainable development offer pathways to a brighter future.

Moreover, there are opportunities for increased cooperation between Haiti and the Dominican Republic on issues of mutual concern, such as environmental conservation, disaster preparedness, and regional economic integration. Such cooperation could benefit both nations and serve as a model for regional collaboration in the Caribbean.

Conclusion

Hispaniola, with its rich history, cultural diversity, and natural wonders, encapsulates many of the challenges and opportunities facing the Caribbean region as a whole. From the heights of Pico Duarte to the mangrove-fringed coasts, from the bustling streets of Santo Domingo to the remote villages of Haiti's mountains, the island offers a microcosm of Caribbean life in all its complexity.

As Haiti and the Dominican Republic navigate the challenges of the 21st century, their people's resilience, creativity, and determination offer hope for a future where the island's natural and cultural riches are preserved and its full potential realized. In many ways, the story of Hispaniola is still being written, with each new chapter offering the possibility of progress, reconciliation, and sustainable development.

Island of Hispaniola location map.