The Caribbean Sea: Ocean Dynamics and Marine Ecosystems of the American Mediterranean

The Caribbean Sea is a captivating semi-enclosed basin connecting North and South America, known for its extraordinary biodiversity. Its semi-enclosed shape gives it a unique oceanographic character, influencing maritime history, ecosystems, and regional climate patterns.

Caribbean Convergence: Where Volcanic Forces Meet Cultural Fusion

The Caribbean Sea stands as one of the world's most fascinating semi-enclosed marine basins. This tropical oceanic realm bridges two vast continents and harbors extraordinary biodiversity within its azure waters. Covering approximately 2.75 million square kilometers (1.06 million square miles), this remarkable sea stretches between North and South America, creating a unique marine environment that has shaped maritime history, supported diverse ecosystems, and continues to influence regional climate patterns across the Western Hemisphere.

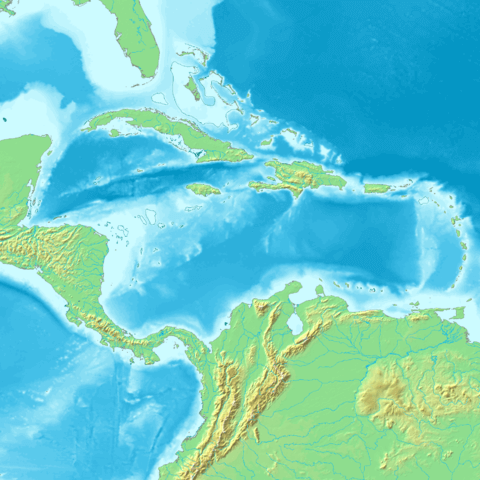

Unlike the vast expanses of open ocean, the Caribbean Sea's semi-enclosed nature creates a distinct oceanographic character. Bounded by the Bahamas and Florida Keys to the northwest, Central America to the west, South America to the south, and the islands of the Caribbean Archipelago forming the Lesser Antilles and Greater Antilles to the north and east, this marine basin functions as a complex system where oceanic currents, freshwater inputs, and atmospheric forces converge to create one of the world's most dynamic marine environments.

Physical Oceanography and Basin Formation

Geological Foundation of a Semi-Enclosed Sea

The Caribbean Sea's unique character as a semi-enclosed basin stems from its complex geological history, which began approximately 130 million years ago during the Cretaceous period. The sea floor consists of oceanic crust formed through a series of tectonic processes that continue to shape the basin today. The Caribbean Plate, a relatively small tectonic plate measuring roughly 3.2 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles), serves as the foundation for this marine realm. The same tectonic forces that created this oceanic basin also shaped the thousands of islands that form the Caribbean Archipelago, creating an intricate relationship between the sea floor and the landmasses that define its boundaries.

The basin's semi-enclosed configuration results from the convergence of three major tectonic plates: the North American, South American, and Caribbean plates. This unique positioning has created a marine environment that is neither fully enclosed like the Mediterranean Sea nor completely open like the Atlantic Ocean. The restricted connections to the broader Atlantic through relatively narrow passages between islands create distinctive oceanographic conditions that define the Caribbean's marine character.

Topographic map of the Caribbean Basin.

Bathymetry and Deep Ocean Features

The Caribbean Sea consists of four deep basins that create a complex underwater topography rivaling any terrestrial mountain range. The deepest point, the Cayman Trench, plunges to 7,686 meters (25,217 feet) below sea level, making it the deepest point in the Caribbean and among the deepest trenches in the Atlantic Ocean system.

The Colombian Basin, located in the southern Caribbean, reaches depths of approximately 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) and covers an area of roughly 330,000 square kilometers (127,413 square miles). This basin receives significant freshwater input from South American rivers, creating unique hydrographic conditions that influence marine life throughout the region.

The Venezuelan Basin, stretching along the northern coast of South America, extends to depths of 5,420 meters (17,782 feet). This basin serves as a critical pathway for deep-water circulation patterns that connect the Caribbean to the broader Atlantic Ocean system.

The Cayman Basin, home to the Cayman Trench, represents one of the most geologically active areas in the Caribbean. The trench formed through transform fault activity between the North American Plate and Caribbean Plate, creating not only extreme depths but also unique deep-sea environments that harbor specialized marine communities.

The Yucatan Basin, located in the western Caribbean, reaches depths of 4,384 meters (14,383 feet) and plays a crucial role in connecting Caribbean waters with the Gulf of Mexico through the Yucatan Channel. This connection allows for significant water exchange that influences both Caribbean and Gulf ecosystems.

Water Circulation and Current Systems

The Caribbean Sea's semi-enclosed nature creates distinctive circulation patterns that differ markedly from open ocean systems. The primary circulation is driven by the Caribbean Current, which enters the basin through passages between the Lesser Antilles islands and flows generally westward at speeds averaging 15-30 centimeters per second (0.3-0.6 knots).

This westward-flowing current system transports approximately 30 million cubic meters (1.06 billion cubic feet) of water per second through the Caribbean, making it one of the most significant current systems in the tropical Atlantic. The current's path is influenced by the basin's complex bathymetry, creating eddies, upwelling zones, and areas of enhanced mixing that support diverse marine ecosystems.

The Loop Current system connects the Caribbean to the Gulf of Mexico through the Yucatan Channel, where Caribbean waters flow northward into the Gulf before eventually exiting through the Florida Straits to join the Gulf Stream. This connection creates a vital link in the Atlantic's thermohaline circulation system, demonstrating how the semi-enclosed Caribbean influences global ocean patterns.

Upwelling zones along the Venezuelan and Colombian coasts create areas of enhanced biological productivity. These regions, where deep, nutrient-rich waters rise to the surface, support some of the Caribbean's most productive marine ecosystems and important commercial fisheries.

Temperature and Salinity Characteristics

The Caribbean Sea's tropical location and semi-enclosed nature create distinctive temperature and salinity patterns. Surface water temperatures remain relatively constant throughout the year, ranging from 26-29°C (79-84°F), with minimal seasonal variation due to the region's proximity to the equator.

The sea's salinity patterns reflect its unique position between continents. Throughout the year, Caribbean seasonal sea-level variability is found to respond to sea surface temperature variability, creating complex interactions between thermal expansion and freshwater inputs from major South American rivers.

The Amazon and Orinoco River plumes significantly influence Caribbean water properties, particularly in the southern and eastern portions of the basin. These massive freshwater inputs can extend hundreds of kilometers from the South American coast, creating distinct water masses with reduced salinity and increased nutrient content that support specialized marine communities.

Deep water temperatures in the Caribbean remain remarkably stable at 4-5°C (39-41°F) below 1,000 meters (3,281 feet), while salinity increases with depth, reaching maximum values of 34.9-35.0 practical salinity units in intermediate waters before decreasing slightly in the deepest basins.

Marine Ecosystems and Biodiversity

Coral Reef Ecosystems: Underwater Rainforests

The Caribbean Sea hosts some of the world's most spectacular coral reef ecosystems, with reef coverage extending across approximately 26,000 square kilometers (10,039 square miles). These underwater landscapes support extraordinary biodiversity, harboring over 65 species of hard corals and more than 1,400 species of fish within a relatively small geographic area.

The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, stretching over 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) from Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula to Honduras, represents the second-largest coral reef system in the world. This magnificent structure demonstrates how the Caribbean's semi-enclosed nature has allowed for the development and maintenance of continuous reef systems that would be impossible in more exposed oceanic environments.

Caribbean coral reefs support critical ecological functions, including nursery habitats for commercially important fish species, coastal protection from wave energy, and carbon cycling processes that influence global climate regulation. Species such as Acropora palmata (elkhorn coral) and Acropora cervicornis (staghorn coral) create complex three-dimensional structures that provide habitat for countless marine organisms.

However, these ecosystems face unprecedented challenges. Rising sea temperatures have triggered widespread coral bleaching events, with some areas experiencing mortality rates exceeding 50% during major bleaching episodes. Ocean acidification, caused by increased atmospheric CO₂ absorption, threatens coral calcification processes essential for reef growth and maintenance.

Pelagic Marine Life: Open Water Communities

The Caribbean's open waters support diverse pelagic communities that take advantage of the sea's unique oceanographic conditions. Large migratory species use the Caribbean as a critical transit corridor, including Thunnus albacares (yellowfin tuna), Coryphaena hippurus (common dolphinfish), and various billfish species that support important commercial and recreational fisheries.

Marine mammal populations in the Caribbean include approximately 30 species, ranging from small coastal dolphins to large baleen whales. The Megaptera novaeangliae (humpback whale) uses Caribbean waters as breeding grounds, with populations migrating from North Atlantic feeding areas to mate and calve in the warm tropical waters.

The critically endangered Trichechus manatus (West Indian manatee) represents one of the Caribbean's most iconic marine mammals, with populations distributed throughout coastal areas and river systems. Current estimates suggest fewer than 10,000 individuals remain, making conservation efforts crucial for the species' survival.

Sea turtle populations demonstrate the Caribbean's importance as a marine biodiversity hotspot. Five sea turtle species regularly occur in Caribbean waters: Chelonia mydas (green turtle), Caretta caretta (loggerhead turtle), Eretmochelys imbricata (hawksbill turtle), Lepidochelys kempii (Kemp's ridley turtle), and Dermochelys coriacea (leatherback turtle). These species utilize Caribbean beaches for nesting and the sea's warm waters for feeding and development.

Deep-Sea Environments: Hidden Biodiversity

Recent deep-sea exploration in the Caribbean has revealed extraordinary biodiversity in the basin's deepest waters. Discoveries include unique isopod crustaceans and other specialized deep-sea organisms adapted to the Caribbean's unique deep-water conditions.

The Cayman Trench harbors unique hydrothermal vent communities that represent some of the deepest known chemosynthetic ecosystems in the Atlantic Ocean system. These vents support specialized organisms that derive energy from chemical processes rather than photosynthesis, including unique species of tube worms, vent crabs, and bacterial mats.

Deep-water coral communities in the Caribbean include significant populations of Lophelia pertusa and other cold-water coral species that create complex three-dimensional habitats in the deep ocean. These communities support diverse fish assemblages and serve as important carbon storage systems in the deep sea.

Unfortunately, recent expeditions have revealed widespread plastic, metal, and glass debris in the deep waters of the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean Sea, highlighting the extent to which human activities impact even the most remote marine environments.

Map of the Caribbean Region.

Climate Interactions and Atmospheric Coupling

The Caribbean as a Hurricane Generator

The Caribbean Sea's semi-enclosed nature and tropical location make it a critical region for Atlantic hurricane formation and intensification. The sea's warm surface waters, typically 26°C (79°F) or higher, provide the thermal energy necessary for tropical cyclone development. Approximately 60% of major Atlantic hurricanes either form within or strengthen significantly while passing through Caribbean waters.

The Caribbean Low-Level Jet, a wind pattern that develops during the summer months, influences both hurricane activity and regional precipitation patterns. This atmospheric feature demonstrates how the Caribbean's unique geographic position between continents creates distinctive climate phenomena that affect both regional and global weather systems.

Hurricane intensity changes within the Caribbean basin often occur rapidly due to the sea's bathymetry and current patterns. Deep, warm waters in the central Caribbean can fuel rapid intensification, while interactions with land masses and varying sea surface temperatures create complex patterns of strengthening and weakening.

Sea Level Rise and Climate Change Impacts

The current sea-level rise in the Caribbean is 3.40 ± 0.3 mm/year (1993–2019), which is similar to the 3.25 ± 0.4 mm/year global mean sea-level rise. This rate of increase poses significant challenges for low-lying coastal areas and coral reef ecosystems throughout the region.

The Caribbean's response to climate change is complicated by its semi-enclosed nature, which can amplify both warming and sea level rise effects. Restricted water exchange with the broader Atlantic means that heat and rising sea levels can become concentrated within the basin, potentially creating more severe local impacts than would occur in open ocean environments.

Thermal expansion contributes significantly to Caribbean sea level rise, with the region experiencing pronounced seasonal variations linked to temperature changes. During summer months, thermal expansion can contribute an additional 10-15 centimeters (4-6 inches) to local sea levels, affecting coastal flooding and erosion patterns.

Freshwater Inputs and Salinity Changes

The Caribbean receives massive freshwater inputs from South American river systems, particularly during seasonal flood periods. The Amazon River discharge averages 200,000 cubic meters (7.06 million cubic feet) per second, while the Orinoco River contributes an additional 35,000 cubic meters (1.24 million cubic feet) per second to Caribbean waters.

These freshwater inputs create distinct water masses that can be tracked hundreds of kilometers from their source, influencing marine ecosystems and regional climate patterns. The Amazon plume, in particular, can extend across the entire width of the Caribbean basin during peak discharge periods, creating a lens of less saline water that affects hurricane development and marine productivity.

Seasonal salinity variations in the Caribbean reflect both river discharge patterns and regional precipitation cycles. During wet seasons, surface salinity can decrease by 2-3 practical salinity units in areas influenced by major river plumes, creating stratification patterns that influence vertical mixing and nutrient distribution.

Maritime History and Human Interactions

Colonial Trade Routes and the Spanish Main

The Caribbean Sea's semi-enclosed nature made it a natural maritime highway during the colonial period, with Spanish, English, French, and Dutch powers establishing complex trade networks that connected Europe, Africa, and the Americas. The sea's configuration, with numerous islands providing sheltered harbors and strategic positions, created ideal conditions for both legitimate trade and piracy.

The Spanish treasure fleets utilized Caribbean trade winds and current patterns to transport gold and silver from South America to Europe, establishing routes that took advantage of the sea's predictable oceanographic conditions. These fleets typically followed the Caribbean Current westward to Mexican ports before catching the Gulf Stream northward toward Spain.

Sugar plantation economies throughout the Caribbean islands relied on the sea for the transportation of enslaved people, raw materials, and finished products. The triangle trade system connected Caribbean sugar production to European markets and African populations, creating economic relationships that fundamentally shaped the region's cultural and social development.

The Golden Age of Piracy

The Caribbean's complex geography, with thousands of islands, hidden coves, and unmarked channels, provided ideal conditions for maritime piracy during the 17th and early 18th centuries. Pirates took advantage of the sea's semi-enclosed nature, using detailed knowledge of local currents, winds, and hiding places to evade naval forces and prey upon merchant shipping.

Port Royal, Jamaica, once known as the "wickedest city on Earth," served as a major pirate haven until its destruction by earthquake in 1692. The port's strategic location allowed pirates to control vital shipping lanes while enjoying protection from the semi-enclosed sea's complex geography.

Tortuga Island off the coast of Haiti became another famous pirate stronghold, demonstrating how the Caribbean's island geography created numerous opportunities for establishing quasi-independent maritime communities that operated outside traditional governmental control.

Modern Maritime Commerce

Today, the Caribbean Sea serves as a crucial link in global maritime trade networks, with major shipping lanes connecting North American and European markets with South American and Asian economies. The Panama Canal system routes approximately 6% of global trade through Caribbean waters, making the sea a critical component of international commerce.

Cruise ship tourism has transformed the Caribbean into one of the world's most visited maritime destinations, with over 30 million passengers annually visiting Caribbean ports. This industry demonstrates how the sea's natural beauty, calm waters, and favorable climate continue to attract human activities, though at scales far exceeding historical levels.

Container shipping routes through the Caribbean connect major ports including Miami, San Juan, Kingston, and Cartagena, handling millions of tons of cargo annually. These shipping patterns reflect the sea's continued importance as a maritime crossroads linking multiple continents and economic systems.

Economic Importance and Resource Utilization

Commercial Fisheries and Marine Resources

The Caribbean Sea supports important commercial fisheries with annual catches valued at over $400 million USD. The semi-enclosed nature of the basin creates productive fishing grounds while also making fish populations vulnerable to overexploitation due to limited connectivity with other ocean systems.

Pelagic fisheries target species such as Thunnus albacares (yellowfin tuna), Katsuwonus pelamis (skipjack tuna), and Coryphaena hippurus (common dolphinfish). These species utilize the Caribbean's warm waters and productive ecosystems for feeding and reproduction, supporting both commercial and recreational fisheries throughout the region.

Reef-associated fisheries provide crucial protein sources for Caribbean populations, with species like Epinephelus striatus (Nassau grouper), various snapper species, and Panulirus argus (Caribbean spiny lobster) supporting both subsistence and commercial fishing operations. However, many reef fish populations have declined significantly due to overfishing and habitat degradation.

Conch fisheries, particularly targeting Strombus gigas (queen conch), represent one of the Caribbean's most valuable marine resources, with annual harvests exceeding 1,000 tons in shell weight. The species' dependence on seagrass habitats makes it particularly vulnerable to coastal development and environmental changes.

Energy Resources and Offshore Development

The Caribbean Sea basin contains significant hydrocarbon resources, with proven oil reserves exceeding 13 billion barrels and natural gas reserves of approximately 55 trillion cubic feet. The semi-enclosed nature of the basin has created geological conditions favorable for hydrocarbon accumulation, particularly along the continental margins.

Trinidad and Tobago produces approximately 60,000 barrels of oil per day from offshore Caribbean fields, while Colombia and Venezuela operate significant offshore production facilities in Caribbean waters. These operations demonstrate the economic importance of the sea's energy resources while also highlighting environmental risks associated with offshore development.

Renewable energy potential in the Caribbean includes significant wind energy resources, with average wind speeds of 7-9 meters per second (16-20 mph) in many areas. Several Caribbean nations are developing offshore wind projects that take advantage of consistent trade winds and relatively shallow continental shelf areas.

Marine Biotechnology and Blue Economy

The Caribbean's unique biodiversity has attracted increasing attention from biotechnology researchers seeking novel compounds for pharmaceutical and industrial applications. Marine sponges, abundant on Caribbean reefs, have yielded compounds with anti-cancer, anti-viral, and antibiotic properties, with several drugs currently in clinical trials.

Coral reef organisms produce complex biochemical compounds for defense, reproduction, and competition, many of which have potential applications in medicine and biotechnology. The Caribbean's high coral diversity makes it a particularly valuable region for bioprospecting activities.

Aquaculture development in the Caribbean focuses on species such as Rachycentron canadum (cobia), various snapper species, and shrimp production. The sea's warm, nutrient-rich waters provide favorable conditions for marine aquaculture, though careful environmental management is essential to prevent negative impacts on natural ecosystems.

Environmental Challenges and Conservation

Pollution and Marine Debris

Recent research has revealed widespread debris in the deep waters of the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean Sea, demonstrating that pollution impacts extend throughout the water column and into the deepest parts of the basin. This pollution comes from both land-based sources and maritime activities.

Plastic pollution in Caribbean waters includes microplastics that enter the marine food web and larger debris that threatens marine life through entanglement and ingestion. The semi-enclosed nature of the Caribbean can trap pollutants, leading to accumulation rates higher than those found in open ocean environments.

Agricultural runoff from surrounding landmasses introduces excessive nutrients into Caribbean waters, leading to eutrophication and harmful algal blooms that can create dead zones with low oxygen levels. Major river systems carrying agricultural pollutants can affect water quality across vast areas of the Caribbean Sea.

Oil pollution from both accidental spills and routine shipping operations poses ongoing threats to Caribbean marine ecosystems. The heavy maritime traffic through Caribbean waters increases the risk of catastrophic spills that could have devastating impacts on coral reefs and coastal communities.

Climate Change Impacts on Marine Ecosystems

Rising ocean temperatures in the Caribbean have triggered repeated coral bleaching events, with major episodes occurring in 1995, 1998, 2005, 2010, 2014-2017, and 2023. These events have caused widespread coral mortality, with some reef systems experiencing over 80% coral cover loss.

Ocean acidification in the Caribbean has decreased seawater pH by approximately 0.1 units since pre-industrial times, making it increasingly difficult for corals and other calcifying organisms to build and maintain their skeletons. This process threatens the structural integrity of entire reef systems.

Sea level rise particularly threatens low-lying coral cays and coastal mangrove systems that serve as critical nursery habitats for marine species. Many Caribbean islands face the prospect of significant land loss, which could eliminate important marine habitats entirely.

Hurricane intensification linked to warming sea surface temperatures creates more frequent and severe disturbances for Caribbean marine ecosystems. While many species have adapted to hurricane impacts over evolutionary time, the increasing frequency and intensity of storms may exceed ecosystems' recovery capabilities.

Conservation Efforts and Marine Protection

The Caribbean region has established numerous marine protected areas covering approximately 20,000 square kilometers (7,722 square miles) of marine habitat. These protected areas range from small reef reserves to large multi-use marine parks that encompass diverse ecosystem types.

The Caribbean Challenge Initiative represents a regional commitment to protect 20% of marine and coastal environments by 2030. This initiative demonstrates unprecedented regional cooperation in marine conservation, with 23 Caribbean countries and territories participating in coordinated protection efforts.

Sea turtle conservation programs throughout the Caribbean have achieved significant success in protecting nesting beaches and reducing mortality from fishing operations. These programs include community-based initiatives that provide alternative livelihoods for local residents while protecting critical marine species.

Coral restoration projects are underway throughout the Caribbean, with scientists developing new techniques for coral propagation, genetic rescue, and assisted evolution. These efforts aim to develop coral populations that can better withstand rising temperatures and changing ocean chemistry.

Research and Scientific Discovery

Ongoing Oceanographic Research

The Caribbean Sea serves as a natural laboratory for studying semi-enclosed ocean systems and their responses to climate change. Research programs including the Caribbean Coastal Ocean Observing System (CARICOOS) provide continuous monitoring of ocean conditions throughout the basin.

Deep-sea exploration programs continue to reveal new species and ecosystems in Caribbean waters. Recent expeditions have documented 100 newly discovered deep-sea animals, including species of deep-sea corals, glass sponges, squat lobsters, and more in various ocean basins, with Caribbean explorations contributing significantly to these discoveries.

Climate research in the Caribbean focuses on understanding how semi-enclosed seas respond to global climate change, with implications for other similar ocean basins worldwide. These studies examine the complex interactions between ocean circulation, atmospheric forcing, and ecosystem responses.

Technological Innovations in Marine Science

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) have revolutionized Caribbean marine research, allowing scientists to explore deep-sea environments and conduct long-term monitoring programs with unprecedented detail and precision.

Satellite oceanography provides comprehensive views of Caribbean sea surface temperatures, chlorophyll concentrations, and current patterns, enabling researchers to track changes across the entire basin and understand large-scale oceanographic processes.

Genetic analysis techniques are revealing previously unknown biodiversity in Caribbean waters, with environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling allowing scientists to detect species presence without physically capturing organisms. These techniques are particularly valuable for studying elusive deep-sea and pelagic species.

Future Research Directions

Ecosystem connectivity studies aim to understand how marine populations are connected across the Caribbean basin and how these connections might change under future climate scenarios. These studies are crucial for designing effective marine protected area networks.

Blue carbon research focuses on quantifying carbon storage in Caribbean coastal ecosystems, particularly seagrass beds and mangrove forests. These ecosystems may store significantly more carbon than previously recognized, making their conservation crucial for climate mitigation efforts.

Marine biotechnology research continues to explore the Caribbean's unique biodiversity for applications in medicine, materials science, and biotechnology. The region's endemic species may harbor compounds and biological processes with significant commercial and scientific value.

Conclusion: The Caribbean Sea in a Global Context

The Caribbean Sea represents far more than a tropical paradise or maritime crossroads—it stands as one of Earth's most remarkable examples of how geographic configuration shapes marine environments and human history. As a semi-enclosed sea positioned between two vast continents, the Caribbean has created unique conditions that support extraordinary biodiversity, influence global climate patterns, and continue to shape economic and social development throughout the Western Hemisphere.

The sea's 2.75 million square kilometers of marine habitat demonstrate how relatively small ocean basins can have impacts far exceeding their geographic size. From generating hurricanes that affect the entire Atlantic basin to supporting coral reef ecosystems that harbor more than 10% of the world's marine biodiversity, the Caribbean Sea punches well above its weight in terms of global significance.

The Caribbean's role as a bridge between continents has created not only unique oceanographic conditions but also distinctive cultural and economic patterns that continue to evolve. The same geographic factors that made the Caribbean a crucial crossroads during the age of exploration now position it as a critical region for understanding climate change impacts, managing marine resources sustainably, and developing new approaches to ocean conservation.

Looking toward the future, the Caribbean Sea faces unprecedented challenges from climate change, pollution, and intensive human use. However, the region's long history of adaptation and resilience, combined with growing scientific understanding and international cooperation, provides hope for maintaining the Caribbean's role as one of the world's most vital and productive marine ecosystems.

The Caribbean Sea's story continues to unfold, shaped by the same physical forces that created this remarkable basin millions of years ago, but now increasingly influenced by human activities that span the globe. Understanding and protecting this unique marine environment will require the same spirit of exploration and cooperation that has defined Caribbean history, ensuring that future generations can continue to benefit from the extraordinary natural and cultural riches of the American Mediterranean.