Coiba Island: The Galápagos of Central America

Coiba Island, located off the western coast of Panama, is a natural paradise characterized by its remarkable biodiversity and unspoiled ecosystems. As the largest island in Central America, Coiba and its surrounding National Park provide a unique refuge for numerous plant and animal species.

Coiba National Park: Panama's Marine Crown Jewel in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Corridor

In the azure waters of the Gulf of Chiriquí, where Pacific currents converge with volcanic islands and pristine coral reefs, lies one of Central America's most extraordinary conservation achievements. Coiba National Park, encompassing 270,125 hectares (667,426 acres) of marine and terrestrial ecosystems around Panama's largest island, represents far more than a protected area—it stands as the cornerstone of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor (CMAR), a revolutionary transboundary initiative connecting marine protected areas from Mexico to Ecuador.

Coiba Island, spanning 503 square kilometers (194 square miles), gained its unique biological significance through isolation that began approximately 12,000 to 18,000 years ago, when rising sea levels separated it from the mainland of Panama. This geographic isolation, combined with the island's dark history as a feared penal colony from 1919 to 2004, inadvertently created one of the most pristine tropical ecosystems in the Americas.

The island's transformation from prison to UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005 represents a remarkable conservation success story that demonstrates how protected areas can emerge from the most unlikely circumstances. UNESCO recognized Coiba National Park under multiple criteria, acknowledging it as "an outstanding example of the process of insular evolution" and highlighting its exceptional marine biodiversity. The World Heritage designation specifically recognizes the park's role as a natural laboratory for scientific research into biological evolution, while also acknowledging its importance as one of the few remaining relatively pristine tropical marine ecosystems. This international recognition not only provides additional protection for the park's unique ecosystems but also emphasizes its global significance as a site where evolutionary processes can be studied in their natural state, making it invaluable for understanding both terrestrial island biogeography and marine ecosystem dynamics.

Within the broader context of marine conservation networks, Coiba National Park serves as both a critical component of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor and the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor, providing essential connectivity between marine protected areas from Costa Rica to Ecuador. While the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor primarily focuses on terrestrial and coastal connectivity from Mexico through Central America, Coiba represents its crucial Pacific marine extension, linking with the specialized Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor that connects iconic marine protected areas, including Costa Rica's Cocos Island, Ecuador's Galápagos Islands, and Colombia's Malpelo Island and Gorgona Island. This corridor represents one of the most biodiverse marine regions in the world, supporting migratory routes for numerous species, including hammerhead sharks, humpback whales, and sea turtles that depend on interconnected protected areas across vast ocean distances.

The Galápagos of Central America: Island Evolution in Action

Coiba Island's 12,000-year separation from mainland Panama has created a natural laboratory for evolution that rivals the famous Galápagos Islands in its scientific significance. The island's isolation has resulted in extraordinary levels of endemism, with numerous subspecies that have evolved in isolation from their mainland relatives, illustrating the profound impact of geographic separation on driving evolutionary processes.

The island's terrestrial ecosystems comprise approximately 2,000 species of vascular plants, with 858 species having been scientifically described. Among these, the genus Desmotes is endemic to Coiba, represented by the unique species Desmotes incomparabilis. Additional endemic plant species include Fleishmania coibensis and Psychotria fosteri, highlighting the island's importance as a center of plant evolution and endemism.

Coiba's forests, covering approximately 75% of the island's surface, represent some of the last remaining primary tropical dry forests on Central America's Pacific coast. These forests rise from sea level to the island's highest point at 425 meters (1,394 feet), creating diverse habitats that support ancient trees that have long vanished from the Panamanian mainland due to deforestation. The forest canopy harbors spectacular emergent trees, including Cecropia obtusifolia, Ficus species, and rare hardwoods that provide crucial habitat for the island's endemic fauna.

The island's unique position within the Eastern Tropical Pacific creates distinct seasonal patterns, influenced by both wet and dry seasons. The Gulf of Chiriquí's capacity to buffer against El Niño temperature swings has created stable conditions, allowing complex ecosystems to develop and persist over millennia.

Endemic Wildlife: Evolution's Island Laboratory

Coiba Island harbors one of Central America's most remarkable assemblages of endemic subspecies, demonstrating how isolation drives evolutionary processes. The island supports several endemic subspecies that have evolved distinct characteristics from their mainland relatives, making it a living laboratory for understanding island biogeography and speciation processes.

Among the most notable endemic subspecies, the Coiba Island howler monkey (Alouatta coibensis coibensis) represents a distinct population that has diverged from mainland howler monkeys through thousands of years of isolation. These primates have adapted to the island's unique forest conditions and exhibit behavioral and morphological differences from their continental relatives.

The avian fauna includes several endemic subspecies, most notably the Coiba spinetail (Cranioleuca dissita), which is found only on Coiba Island and represents a monotypic species that has evolved in isolation. The brown-backed dove (Leptotila battyi) is a distinct subspecies on the island, while numerous other bird species exhibit varying degrees of genetic differentiation from mainland populations.

Coiba's forests provide refuge for Central America's largest population of scarlet macaws (Ara macao), with the island supporting one of the most viable populations of this threatened species on the Pacific coast. The crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis) finds sanctuary in the island's pristine forests, representing one of the few remaining strongholds for this powerful raptor in Central America.

The island's reptile fauna includes several endemic subspecies adapted to island conditions, while the absence of large terrestrial predators has allowed unique evolutionary pressures to shape the development of endemic taxa across multiple taxonomic groups.

Marine Biodiversity: A Pacific Ocean Sanctuary

Coiba National Park's marine ecosystems rival those of the Galápagos Islands in their extraordinary biodiversity and endemism. The park's marine areas support 760 species of marine fish, 33 species of sharks, and 20 species of cetaceans, creating one of the most biodiverse marine protected areas in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

The park's unique position within the Eastern Tropical Pacific creates conditions that support both tropical and temperate marine species. The confluence of different ocean currents creates upwelling zones that bring nutrient-rich waters, supporting spectacular marine productivity. These conditions attract large pelagic species, including scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini), whale sharks (Rhincodon typus), and various billfish species that use the area as feeding and nursery grounds.

The park's coral reefs represent some of the most pristine examples of Eastern Tropical Pacific reef ecosystems, supporting complex biological interactions among their inhabitants while providing crucial ecological links for the transit and survival of numerous pelagic fish species. These reefs harbor numerous endemic fish species and support breeding populations of species that are rare or absent from other parts of their range.

Marine mammal diversity includes resident populations of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and spotted dolphins (Stenella attenuata), while seasonal visitors include humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) from both Northern and Southern Hemisphere populations, making Coiba one of the few places where these distinct populations overlap during their migrations.

Sea turtle populations include four species that nest on the park's pristine beaches: olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), green (Chelonia mydas), and leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), with the island's beaches providing crucial nesting habitat free from the development pressures that threaten turtle populations throughout much of their range.

The Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor: Ocean Connectivity

Coiba National Park serves as a cornerstone of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor, a visionary conservation initiative established in 2004 through the San José Declaration as a voluntary regional cooperation mechanism between Ecuador, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Panama. This corridor represents one of the most ambitious marine conservation efforts in the world, recognizing that effective ocean conservation requires thinking beyond individual protected areas to encompass entire migration routes and ocean basins.

The corridor connects Coiba with other iconic marine protected areas, including Costa Rica's Cocos Island, Ecuador's Galápagos Islands, and Colombia's Malpelo and Gorgona Islands, creating a network of stepping stones that supports a wide range of marine species across vast ocean distances. This connectivity proves essential for species such as hammerhead sharks, which undertake remarkable migrations between islands to feed, breed, and seek refuge.

Recent scientific research has revealed the critical importance of these connections, with satellite tagging studies showing that individual sharks and rays may visit multiple islands within the corridor system during their lifetimes. The corridor's designation as an Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSA) under the Convention on Biological Diversity underscores its global significance for marine conservation.

The corridor's significance extends beyond species conservation to encompass ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, climate regulation, and fisheries productivity, that benefit both local and global communities. The pristine condition of Coiba's marine ecosystems makes it particularly valuable as a reference site for understanding how healthy ocean ecosystems should function in an era of unprecedented human impact.

Scientific Research and Discovery

Coiba National Park serves as one of the Pacific's most important centers for tropical marine and terrestrial research, hosting numerous studies that contribute to our understanding of island evolution, marine ecology, and conservation biology. The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute has established the Coibita Field Station on nearby Coibita Island, creating a state-of-the-art research facility that provides access to Coiba's unparalleled biodiversity.

Long-term research programs within the park have produced groundbreaking insights into island biogeography, species evolution, and ecosystem functioning. Studies of endemic subspecies provide crucial data on how isolation drives evolutionary processes, while marine research contributes to the understanding of Eastern Tropical Pacific oceanography and the dynamics of its ecosystems.

The park's role as a natural laboratory becomes increasingly important as researchers seek to understand ecosystem responses to climate change, ocean acidification, and other global environmental changes. The pristine condition of Coiba's ecosystems provides baseline data that cannot be obtained from more disturbed areas, making the park invaluable for comparative studies and long-term monitoring programs.

International research collaborations involving institutions from Panama, the United States, and other countries have made Coiba a focal point for tropical biology education and training. The park's unique combination of terrestrial and marine ecosystems provides opportunities for interdisciplinary research that bridges traditionally separate fields of study.

Conservation Through Isolation: From Prison to Paradise

Coiba Island's conservation success story represents one of the most unusual examples of habitat protection through human exclusion. The establishment of a penal colony in 1919, which operated until 2004, inadvertently created nearly a century of protection from the deforestation, hunting, and development that devastated much of Panama's Pacific coast forests.

During the era of military dictatorships under Omar Torrijos and Manuel Noriega, the island's prison gained notoriety for its harsh conditions, which effectively deterred the general population from visiting the area. This fear-based protection, while achieved through unfortunate circumstances, allowed Coiba's ecosystems to remain largely intact while similar habitats on the mainland were destroyed or severely degraded.

The closure of the prison in 2004 and the island's designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005 marked the beginning of a new era focused on scientific research, conservation, and carefully managed ecotourism. This transformation from a place of punishment to a site of preservation demonstrates how protected areas can emerge from unexpected circumstances when conservation vision meets political will.

Today, the National Authority for the Environment of Panama manages the park through strict access controls that require permits for all visitors, ensuring that human activities remain compatible with conservation objectives. This controlled access approach has proven essential for maintaining the ecological integrity that makes Coiba so valuable for both research and conservation.

Conservation Challenges and Management Innovation

Despite its protected status and remote location, Coiba National Park faces significant conservation challenges that require innovative management approaches. Invasive species introduced during the penal colony era, including feral pigs, cattle, and rats, continue to threaten native ecosystems and require ongoing control efforts.

Climate change presents long-term challenges as rising sea levels threaten nesting beaches for sea turtles, while ocean warming and acidification may affect marine ecosystems. The park's role within the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor becomes increasingly important as species may need to shift their ranges in response to changing conditions.

Illegal fishing poses an ongoing enforcement challenge in the park's marine areas, necessitating effective coordination among park authorities, the Panamanian Navy, and international partners to patrol the vast marine areas. The economic value of shark fins and other marine products creates strong incentives for illegal extraction, which requires constant vigilance to prevent.

The park's success in maintaining ecological integrity while allowing sustainable research and tourism provides a model for other marine protected areas in the region. Innovative management approaches, including community engagement, scientific monitoring, and international cooperation, demonstrate how isolated protected areas can contribute to broader conservation networks.

Economic Dimensions and Sustainable Development

Coiba National Park showcases the significant economic potential of marine conservation through sustainable tourism, research activities, and the provision of ecosystem services. The park attracts diving enthusiasts, researchers, and nature lovers from around the world, generating income for local communities while creating economic incentives for conservation.

The park's pristine marine ecosystems and extraordinary biodiversity make it a premier destination for underwater photography, marine research, and nature-based education programs. Carefully managed tourism ensures that visitor activities support rather than threaten conservation objectives while providing meaningful economic benefits to surrounding coastal communities.

The park's role in supporting fisheries productivity extends its economic benefits well beyond park boundaries. Healthy marine ecosystems within the park serve as sources of larvae and juveniles that replenish fish populations in surrounding waters, supporting artisanal and commercial fisheries throughout the region.

Scientific research activities generate additional economic benefits through the employment of local guides, boat operators, and support staff. Meanwhile, the international attention focused on the park contributes to Panama's reputation as a leader in marine conservation and sustainable development.

A Vision for Marine Conservation

Coiba National Park represents more than an impressive protected area; it embodies a vision of conservation that recognizes the interconnectedness of ocean ecosystems across vast distances and political boundaries. Its success demonstrates how isolated protected areas can serve as crucial nodes in conservation networks that span entire ocean basins.

The park's role within the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor underscores the importance of considering the broader context beyond individual protected areas, encompassing entire ecosystems and migration routes. This network approach to conservation provides hope for maintaining marine biodiversity in an era of unprecedented human impact on ocean systems.

From the pristine beaches where sea turtles nest under starlit skies to the deep waters where hammerhead sharks follow ancient migration routes, Coiba National Park continues to demonstrate that effective conservation requires protecting entire ecosystems rather than individual species. As climate change and other global challenges intensify pressure on marine ecosystems, places like Coiba become increasingly valuable as refugia for biodiversity and natural laboratories for understanding how ecosystems respond to environmental change.

In the calls of endemic birds echoing across island forests and the graceful movements of whale sharks through crystal-clear waters, in the sustainable livelihoods of coastal communities and the wonder of researchers from around the world, Coiba National Park stands as a testament to what can be achieved when conservation vision meets scientific understanding and political commitment. As Panama's marine crown jewel and a cornerstone of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor, the park represents both a monument to conservation success and a beacon of hope for the future of marine biodiversity protection in one of the world's most spectacular ocean regions.

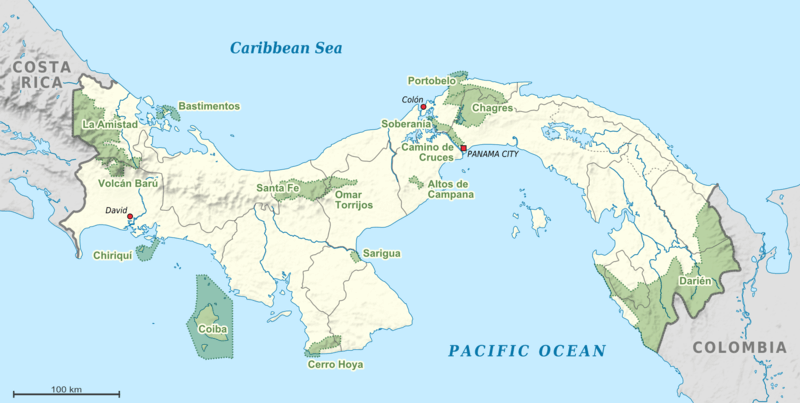

Map depicting the location of the National Parks of Panama.