The Chilean Matorral: Biodiversity Jewel of the Mediterranean World

Nestled between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific Ocean, the Chilean Matorral is one of Earth's biodiversity hotspots. This Mediterranean-climate region serves as a unique evolutionary laboratory, where ancient lineages have thrived in isolation, resulting in one of the most endemic-rich ecosystems.

The Chilean Matorral: A Mediterranean Jewel on South America's Pacific Coast

Nestled between the towering Andes Mountains and the endless Pacific Ocean, the Chilean Matorral ecoregion stands as one of Earth's most remarkable biodiversity hotspots. This Mediterranean-climate jewel, spanning from 32° to 37° south latitude, represents far more than a simple geographic designation—it embodies a unique evolutionary laboratory where ancient lineages have flourished in isolation, creating one of the world's most endemic-rich ecosystems. Despite occupying less than 1% of South America's landmass, the Chilean Matorral harbors an extraordinary 95% endemic flora, making it a conservation priority of global significance while simultaneously serving as Chile's agricultural and viticultural heartland.

Geographic Context and Physical Framework

The Chilean Matorral ecoregion occupies a strategic coastal position along South America's western margin, forming a narrow but ecologically complex corridor between two of the continent's most dominant geographical features. To the west lies the vast Pacific Ocean, whose moderating influence creates the stable temperature regimes characteristic of Mediterranean climates. To the east, the southern Andes rise dramatically from the Central Valley floor, creating a formidable barrier that isolates the ecoregion from continental weather patterns while generating the orographic precipitation that sustains its winter-wet climate regime.

This geographic positioning creates a distinctive tripartite landscape structure that fundamentally shapes the ecoregion's ecological patterns. The Chilean Coastal Range parallels the Pacific shoreline, forming a series of low mountains and hills that intercept marine moisture and create localized climate gradients. Between this coastal cordillera and the main Andean chain stretches the Chilean Central Valley, a fertile depression that has become the foundation of Chile's agricultural economy. The eastern boundary is defined by the Andean foothills, where Mediterranean vegetation gradually transitions to montane forest communities at higher elevations.

The ecoregion's latitudinal extent places it at a critical biogeographical transition zone. To the north, the Chilean Matorral gives way to the hyperarid Atacama Desert, one of Earth's most extreme environments, creating one of the planet's sharpest ecological gradients. This abrupt transition from Mediterranean shrublands to absolute desert reflects the dramatic influence of the Humboldt Current system and subtropical high-pressure cells on regional climate patterns. Southward, the ecoregion transitions gradually into the temperate rainforests of the Valdivian ecoregion, creating a more gradual but equally significant ecological boundary.

Climate: One of Five Mediterranean Worlds

The Chilean Matorral belongs to an exclusive club of only five Mediterranean-climate regions worldwide, each located along the western coasts of continents between approximately 30° and 40° latitude. This climatic regime, characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters, creates unique ecological conditions that support distinctive plant and animal communities found nowhere else on Earth.

The Mediterranean climate of the Chilean Matorral results from the complex interaction of several atmospheric and oceanic systems. During winter months, the westerly wind belt shifts northward, bringing moisture-laden storms from the Pacific Ocean that deliver 80-90% of the region's annual precipitation. Summer months are dominated by the Pacific High, a stable high-pressure system that deflects storms northward and creates the characteristic dry season that can extend for six to eight months.

The moderating influence of the Pacific Ocean creates relatively mild temperature conditions throughout the year, with average summer temperatures rarely exceeding 25°C (77°F) and winter temperatures seldom dropping below 5°C (41°F). However, significant microclimatic variation exists within the ecoregion, driven by topographic complexity, elevation gradients, and proximity to the ocean. Coastal areas experience the most stable temperatures and highest humidity, while interior valleys can experience greater temperature extremes and lower precipitation totals.

This climatic regime creates profound adaptive challenges for vegetation, requiring species to survive extended periods of summer drought while maximizing growth during the brief, moist winter period. The evolutionary responses to these constraints have produced the distinctive sclerophyllous vegetation that characterizes Mediterranean ecosystems worldwide, with hard, waxy leaves that minimize water loss and deep root systems that access groundwater during dry periods.

Biodiversity: An Endemic Paradise

The Chilean Matorral's biodiversity represents one of nature's most remarkable evolutionary experiments, where geographic isolation and climatic stability have allowed unique lineages to diversify into an extraordinary array of endemic species. With approximately 95% of its flora found nowhere else on Earth, the ecoregion ranks among the world's most endemic-rich ecosystems, comparable to oceanic islands in terms of biological uniqueness while maintaining the ecological complexity of continental systems.

This exceptional endemism reflects the ecoregion's complex biogeographic history, which includes periods of connection to other southern continents during the Gondwanan era, followed by millions of years of isolation as South America separated and drifted westward. The flora exhibits fascinating biogeographic affinities that tell the story of this ancient heritage: tropical elements that persist as relicts from warmer periods, Antarctic connections that reflect Gondwanan origins, and Andean influences that demonstrate ongoing mountain building and climatic change.

Plant Communities: A Mosaic of Adaptations

The Chilean Matorral encompasses several distinct plant communities, each representing different adaptive strategies for surviving Mediterranean climate conditions while reflecting local variations in soil, topography, and microclimate.

Coastal Matorral extends as a continuous band of low, soft scrubland from La Serena in the north to Valparaíso in the south, directly influenced by Pacific Ocean fog and salt spray. This community is dominated by drought-tolerant shrubs with succulent or heavily sclerophyllous leaves, many showing remarkable convergent evolution with Mediterranean shrublands of other continents. The persistent influence of marine fog creates conditions that support a unique assemblage of species adapted to both drought stress and high atmospheric humidity.

Interior Matorral represents the classic Mediterranean shrubland community, composed of diverse shrubs, small trees, cacti, and bromeliads arranged in complex spatial patterns that reflect competitive interactions and resource availability. This community exhibits the greatest species diversity within the ecoregion, with numerous microhabitats supporting specialized endemic species. The structural complexity ranges from dense, impenetrable thickets to more open formations that allow for the development of a herbaceous understory.

Espinal communities create distinctive savanna-like landscapes characterized by widely spaced clumps of trees with an understory dominated by annual grasses. These formations typically occur in areas with slightly higher precipitation or access to groundwater, allowing for the establishment of larger woody species while maintaining the open structure that characterizes Mediterranean savannas worldwide.

Sclerophyll Woodlands and Forests once covered extensive areas of the ecoregion but now persist only in small, fragmented patches within the coastal ranges and Andean foothills. These communities are dominated by evergreen trees with thick, waxy leaves, representing some of the ecoregion's most ancient lineages. Many of these forest remnants harbor the highest concentrations of endemic species and serve as critical refugia for rare and threatened taxa.

Flagship Endemic Species

The Chilean Matorral's endemic flora includes numerous species of extraordinary scientific and conservation significance. Gomortega keule represents one of the world's most primitive flowering plants, belonging to a monotypic family that provides crucial insights into angiosperm evolution. This critically endangered tree exists in only a few populations and represents a direct link to the flora of ancient Gondwana.

Pitavia punctata, another monotypic genus, demonstrates the ecoregion's role as a refuge for ancient lineages that have disappeared elsewhere. Nothofagus alessandrii, the endangered ruil, represents the northernmost extent of the southern beech genus and faces severe threats from habitat fragmentation and climate change.

Jubaea chilensis, the Chilean wine palm, stands as one of the world's most massive palm species and Chile's only native palm. Once widespread throughout the ecoregion, this spectacular species now survives in only a few scattered populations, primarily due to centuries of exploitation for palm honey production.

Faunal Diversity and Endemism

The Chilean Matorral's fauna, while less diverse than its flora, includes numerous endemic species that reflect similar patterns of isolation and adaptive radiation. Seven endemic bird species occupy various elevations and habitat types, from rocky coastal slopes to interior scrublands. These avian endemics have evolved specialized feeding strategies and habitat requirements that tie them closely to specific plant communities within the ecoregion.

Mammalian diversity includes several species of continental significance, including the puma (Puma concolor), which serves as the ecosystem's apex predator and plays crucial roles in maintaining ecological balance. The Chilean pudu (Pudu puda), South America's smallest deer, represents an endemic cervid that has adapted to dense shrubland environments. The endangered Andean mountain cat (Leopardus jacobita) occurs at the ecoregion's eastern margins, where Mediterranean shrublands transition to Andean environments.

The degu (Octodon degus) deserves special mention as a keystone species whose ecological role extends far beyond its modest size. This endemic rodent serves as a primary consumer of shrub vegetation while creating extensive burrow systems that modify soil structure and hydrology. Degus also serve as important prey for numerous predators, and their social behaviors have made them valuable subjects for neuroscience and behavioral research.

Reptilian diversity includes several endemic species from the Liolaemus genus, a group of small lizards that has undergone remarkable adaptive radiation throughout South America's western regions. These lizards inhabit diverse microhabitats within Mediterranean shrublands, demonstrating the fine-scale ecological specialization that characterizes many of the ecoregion's endemic species.

Economic and Cultural Significance

The Chilean Matorral serves as the economic and cultural heart of modern Chile, supporting the vast majority of the country's population while producing agricultural products of global importance. This dual role as a biodiversity hotspot and economic center creates complex management challenges that require balancing conservation priorities with human development needs.

Viticultural Excellence

The ecoregion's Mediterranean climate has established Chile as one of the world's premier wine-producing regions, with vineyards scattered throughout the Central Valley and coastal ranges producing internationally acclaimed vintages. The climatic conditions that support endemic shrubland vegetation—warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters—prove equally suitable for grape cultivation, creating economic opportunities that can potentially support conservation efforts through sustainable land management practices.

Chilean wines have gained global recognition not only for their quality but also for their distinctive terroir, which reflects the unique soils, climate, and topography of the Mediterranean ecoregion. This viticultural success demonstrates how human activities can potentially coexist with biodiversity conservation when properly managed, though significant challenges remain in balancing agricultural expansion with habitat protection.

Agricultural Productivity

Beyond viticulture, the Chilean Matorral encompasses Chile's primary agricultural heartland, producing fruits, vegetables, and grains that supply both domestic markets and international export trade. The fertile soils of the Central Valley, combined with reliable irrigation systems that supplement natural precipitation, create some of South America's most productive agricultural landscapes.

This agricultural productivity has supported human settlement for millennia, from indigenous communities that developed sophisticated farming systems to modern industrial agriculture that feeds much of Chile's population. The long history of human land use has profoundly shaped the contemporary landscape, creating a complex mosaic of natural vegetation remnants, agricultural fields, and urban development.

Conservation Challenges: A Threatened Paradise

Despite its extraordinary biodiversity and global significance, the Chilean Matorral faces severe conservation challenges that have made it the least protected ecoregion in Chile in terms of national parks and preserves. The convergence of high biodiversity, dense human population, and intensive land use creates a conservation crisis that requires immediate and sustained action.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

Centuries of human settlement and land conversion have reduced natural vegetation cover to scattered fragments, many of which are too small to maintain viable populations of endemic species. Urban expansion from major cities like Santiago and Valparaíso continues to consume natural habitats, while agricultural expansion replaces native shrublands with exotic crops and pastures.

The fragmentation of remaining natural areas creates edge effects that alter microclimate conditions, facilitate invasion by exotic species, and disrupt ecological processes that depend on landscape-scale connectivity. Many endemic species with specialized habitat requirements find themselves restricted to ever-smaller refugia that may not provide sufficient resources for long-term survival.

Exotic Species Invasions

The Mediterranean climate, which supports exceptional native biodiversity, also proves suitable for numerous exotic species from other Mediterranean regions worldwide. European grasses, shrubs, and trees have established extensive populations that compete with native species for space, water, and nutrients. Some exotic species alter fire regimes, soil chemistry, or hydrology in ways that further disadvantage native communities.

The problem of exotic species invasion is compounded by ongoing habitat disturbance, which creates opportunities for colonization while simultaneously stressing native species and reducing their competitive ability. Climate change may exacerbate these problems by creating novel environmental conditions that favor exotic species over native species adapted to historical climate patterns.

Climate Change Impacts

As a Mediterranean climate region, the Chilean Matorral faces particular vulnerability to climate change impacts that could fundamentally alter the environmental conditions that support its unique biodiversity. Climate models predict significant changes in precipitation patterns, with potential reductions in winter rainfall and alterations in the timing and intensity of storms.

Temperature increases could shift the boundaries between Mediterranean and adjacent ecoregions, potentially facilitating the southward expansion of desert conditions or the northward advance of temperate forest species. Such changes would create novel environmental conditions for which many endemic species lack evolutionary experience, potentially leading to local extinctions and community reorganization.

Water Resource Conflicts

The Chilean Matorral's position as both a biodiversity hotspot and an agricultural center creates intense competition for limited water resources. Agricultural irrigation, urban water supply, and ecosystem maintenance all compete for the same renewable water sources, creating conflicts that are likely to intensify as population growth and climate change continue.

Many endemic plant communities depend on specific hydrological conditions, including seasonal flooding, access to groundwater, or particular soil moisture regimes. Alterations to watershed hydrology, such as those caused by dam construction, groundwater pumping, or land use changes, can have cascading effects on ecosystem structure and function.

Conservation Strategies and Future Directions

Effective conservation of the Chilean Matorral requires innovative approaches that address the complex interactions between biodiversity protection, human development, and sustainable resource management. Traditional conservation strategies, while necessary, focus on establishing protected areas, but are insufficient given the limited availability of unmodified land and the landscape-scale nature of many ecological processes.

Integrated Landscape Management

Future conservation efforts must embrace integrated landscape management approaches that seek to maintain ecological connectivity and ecosystem function across mosaics of protected areas, agricultural lands, and urban development. This approach requires collaboration among government agencies, private landowners, agricultural producers, and conservation organizations to develop land use practices that support both human livelihoods and biodiversity conservation.

Agroecological practices that incorporate native vegetation into agricultural landscapes can provide habitat corridors for wildlife movement while potentially improving agricultural productivity through enhanced pollination, pest control, and soil conservation services. Vineyard management practices that maintain native vegetation buffers and minimize pesticide use demonstrate how agricultural production can coexist with biodiversity conservation.

Restoration and Rewilding

Large-scale restoration efforts provide opportunities to reconnect fragmented habitats while offering economic benefits through the provision of ecosystem services. Restoration of degraded agricultural lands, abandoned mine sites, and disturbed watersheds can create new habitat for endemic species while improving water quality, carbon sequestration, and soil stability.

Rewilding initiatives that reintroduce native species and restore natural ecological processes show promise for ecosystem recovery, though they must be carefully designed to address the novel environmental conditions created by centuries of human modification.

Ex-Situ Conservation and Genetic Resources

Given the immediate threats facing many endemic species, ex-situ conservation programs that maintain genetic diversity in botanical gardens, seed banks, and breeding facilities provide crucial insurance against extinction. These programs must be coupled with habitat protection and restoration efforts to ensure that conserved genetic resources can eventually be returned to wild populations.

The unique genetic resources of Chilean Matorral species may also prove valuable for developing crops and other useful products adapted to Mediterranean climates worldwide, creating economic incentives for conservation while contributing to global food security and climate adaptation.

Conclusion

The Chilean Matorral stands as one of Earth's most remarkable ecoregions, where the convergence of Mediterranean climate, geographic isolation, and evolutionary time has created a biodiversity treasure trove of global significance. With 95% of South America's endemic flora compressed into less than 1% of the continent's area, this ecoregion represents an irreplaceable component of global biodiversity that demands urgent and sustained conservation action.

The challenges facing the Chilean Matorral—habitat fragmentation, exotic species invasion, climate change, and resource conflicts—are formidable but not insurmountable. Success will require innovative conservation approaches that recognize the ecoregion's dual role as a biodiversity hotspot and economic center, developing strategies that support both ecological integrity and human livelihoods.

The viticultural excellence that has brought global recognition to Chilean wines demonstrates the potential for human activities to coexist with Mediterranean ecosystems when properly managed. Expanding this model to encompass broader landscape management approaches could provide a foundation for conservation success that serves as an example for other Mediterranean regions worldwide.

Ultimately, the future of the Chilean Matorral depends on recognizing its global significance and investing in the innovative conservation approaches needed to address 21st-century challenges. The loss of this ecoregion's unique biodiversity would represent an irreversible impoverishment of Earth's biological heritage, while its successful conservation could demonstrate humanity's capacity to balance development with stewardship of the natural world.

The Chilean Matorral's endemic species, from the ancient Gomortega keule to the charismatic Chilean wine palm, serve as ambassadors for conservation efforts that extend far beyond Chile's borders. In protecting this Mediterranean jewel, we preserve not only a unique evolutionary heritage but also a living laboratory for understanding how ecosystems respond to environmental change and how human societies can develop sustainable relationships with the natural world.

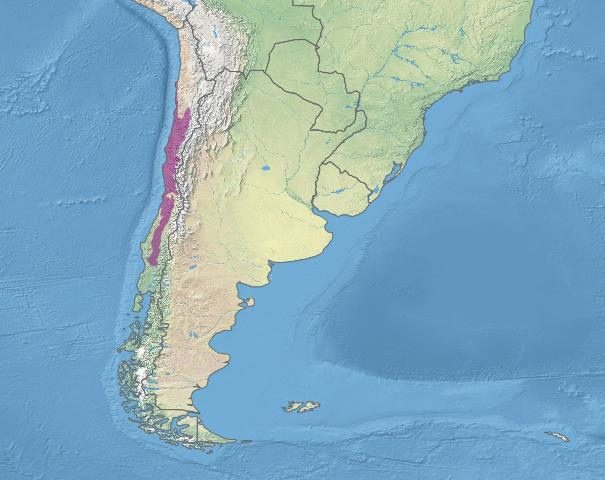

Map depicting the location of the Chilean Matorral (in purple).