The Chilean Coastal Range and Central Valley: Chile's Geographic Foundation

The Chilean Coastal Range and Central Valley form two distinctive geographic features that run parallel down Chile's extraordinary length. The Coastal Range rises as a barrier between the Pacific Ocean and the interior, while the Central Valley nestles between the coastal mountains and the Andes.

From Coastal Peaks to Wine Valleys: Chile's Defining Landscapes

The Chilean Coastal Range and Central Valley form two distinctive geographic features that run parallel down Chile's extraordinary length, creating the foundation for the nation's climate, agriculture, and urban life. The Coastal Range rises as a barrier between the Pacific Ocean and the interior, while the Central Valley nestles between these coastal mountains and the towering Andes, creating Chile's most fertile and populated corridor. Together, they define where rain falls, where forests grow, where crops flourish, and where cities rise—shaping one of South America's most geographically distinctive countries.

The Chilean Coastal Range: Chile's Western Wall

An Ancient Mountain Chain

The Chilean Coastal Range (Cordillera de la Costa) stretches approximately 3,000 km (1,864 miles) along the Pacific coast, from Morro de Arica in the north to the Taitao Peninsula in the south. Unlike the young, volcanic Andes to the east, the Coastal Range consists of much older rocks—some dating back 300-500 million years. This ancient range includes metamorphic basement rocks, granitic intrusions, and volcanic sequences that tell a complex geological story.

The range reaches its highest point at Sierra Vicuña Mackenna in the Antofagasta Region, climbing to 3,114 m (10,216 ft). From there, it gradually decreases in elevation as it extends southward, with central sections typically ranging from 600-1,200 m (1,969-3,937 ft) and southern portions fragmenting into lower coastal hills and islands.

Regional Character

Northern Section: In Chile's hyperarid north, the Coastal Range rises steeply from the Pacific, creating dramatic coastal cliffs. The extreme dryness has preserved ancient landforms virtually unchanged for millions of years. Coastal fog (camanchaca) sustains unique island ecosystems called lomas on the western slopes, where hardy plants and endemic species survive despite receiving almost no rainfall.

Central Section: Between the Copiapó and Aconcagua rivers, the range temporarily merges with the Andes before separating again near Santiago. This creates important corridors that channel Pacific moisture inland. The central Coastal Range hosts Chile's richest Mediterranean ecosystems, including endangered Chilean wine palms and dense sclerophyll forests of southern beech and Chilean myrtle.

Southern Section: South of the Biobío River, the range becomes increasingly fragmented. The Nahuelbuta Range rises to 1,565 m (5,135 ft) and harbors isolated populations of monkey puzzle trees (Araucaria araucana), usually found only at higher Andean elevations. Further south, the range breaks into the coastal archipelago, including Chiloé Island and the Chonos Archipelago.

Climate Maker and Rain Catcher

The Coastal Range acts as Chile's first line of defense against Pacific weather systems. Moisture-laden winds rise as they hit the western slopes, cool, and drop their rain—sometimes over 2,000 mm (79 inches) annually in central and southern sections. This creates lush, green western slopes.

On the eastern side, air descends and warms, creating a rain shadow effect. The Central Valley receives 30-50% less precipitation than the coast, making it much drier. In northern Chile, this double rain shadow (combined with the Andes) helps create the Atacama Desert, one of Earth's driest places.

Biodiversity Haven

Despite human impacts, the Coastal Range remains a biodiversity hotspot. The western slopes of the central range harbor Mediterranean-type ecosystems with exceptional numbers of endemic species found nowhere else on Earth. The critically endangered Chilean wine palm, the world's southernmost palm species, survives in small coastal populations. The range also provides habitat for the endangered Chilean huemul deer, mountain viscacha, and numerous endemic bird species.

Human Footprint

The Coastal Range remains sparsely populated compared to the coastal lowlands and the Central Valley. Mining dominates in the mineral-rich north, particularly in the extraction of copper, iron, and gold. Central regions support forestry operations (both native forests and pine/eucalyptus plantations), valley agriculture, and expanding urban development as coastal cities grow. The south retains more native forest cover, with increasing focus on conservation and ecotourism.

The Central Valley: Chile's Productive Heart

A Great Longitudinal Basin

The Central Valley (Valle Central or Depresión Intermedia) extends roughly 1,000 km (621 miles) from near Santiago to Puerto Montt. This structural basin formed through tectonic subsidence and was filled with volcanic debris and sediments eroded from the rising Andes over millions of years. These deposits, enriched with volcanic ash, created the exceptionally fertile soils that make the valley Chile's agricultural engine.

Changing Landscapes

The valley's character transforms dramatically from north to south. Near Santiago, it forms a broad trough 40-80 km (25-50 miles) wide at elevations of 500-700 m (1,640-2,297 ft). Major rivers flowing from the Andes—including the Aconcagua, Maipo, Maule, and Biobío—carve across the valley, depositing rich alluvial soils and providing irrigation water.

South of the Biobío River, the valley narrows and descends through a spectacular lake district featuring Lago Villarrica, Lago Llanquihue, and numerous smaller glacial lakes. By Puerto Montt at approximately 41°S latitude, the valley reaches sea level. Beyond this point, the valley has been submerged by post-glacial sea level rise, creating Chile's famous fjordland with its maze of channels and islands.

Climate Zones

The valley's climate shifts from semi-arid Mediterranean near Santiago (with about 300 mm or 12 inches of annual rainfall) to temperate oceanic at Puerto Montt (over 2,500 mm or 98 inches). Central regions experience a pronounced 6-8 month dry summer, making irrigation essential for agriculture. Water comes primarily from Andean snowmelt, though climate change is reducing snowpack and creating management challenges.

Agricultural Powerhouse

The Central Valley produces the majority of Chile's food and agricultural exports. The combination of fertile volcanic soils, reliable irrigation, Mediterranean climate, and flat terrain creates ideal farming conditions.

The valley between Santiago and Chillán hosts Chile's world-renowned wine regions—Maipo, Colchagua, Curicó, and Maule. Warm, dry summers and cool nights preserve grape acidity and develop complex flavors. Beyond wine, the valley produces table grapes, apples, pears, cherries, wheat, corn, and sugar beets.

Southern sections shift to different systems, with the Los Lagos Region becoming Chile's dairy heartland. Abundant rainfall supports year-round pasture growth, reducing irrigation needs but also raising environmental concerns about forest conversion and water pollution.

Urban Concentration

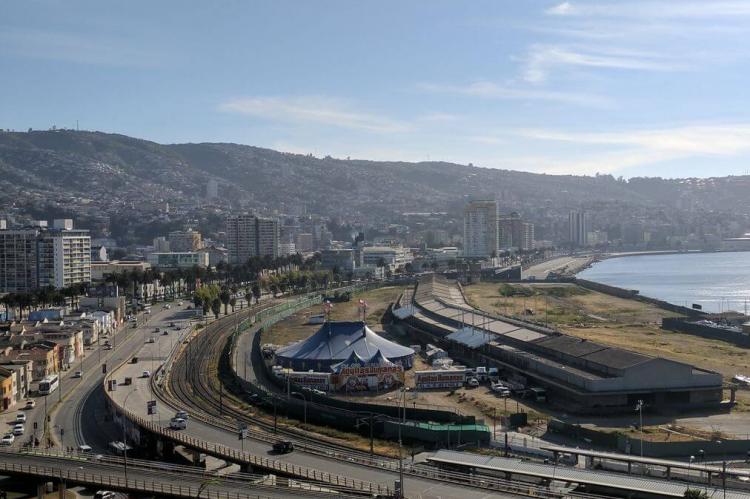

Over 10 million people—about 60% of Chile's population—live in the Central Valley. Santiago, the capital, dominates with over 7 million residents. The city occupies a dramatic basin surrounded by the Coastal Range to the west and the towering Andes to the east.

Other major cities include Rancagua (the heart of copper country), Talca (an agricultural hub), Chillán (known for nearby ski resorts), Concepción (Chile's second-largest metro area), and Temuco (capital of Mapuche territory). This population concentration creates economic opportunities but also environmental pressures, including air pollution, water scarcity, and loss of farmland to urban sprawl.

Environmental Challenges

Centuries of intensive use have transformed the valley. Original Mediterranean woodlands have been reduced to small fragments. Wetlands and riparian forests have largely disappeared. Soil degradation, water over-extraction, and pollution affect large areas. Santiago's air quality frequently exceeds health standards due to vehicle emissions and winter wood burning, which are trapped by temperature inversions.

Conservation efforts remain limited in Chile's most productive region, highlighting the ongoing challenge of balancing economic development with environmental protection.

Two Landscapes, One Story

The Coastal Range and Central Valley don't exist in isolation—they're intimately connected. The Coastal Range creates the rain shadow that gives the Central Valley its Mediterranean climate. That climate, combined with Andean water and volcanic soils, makes the valley agriculturally productive. Meanwhile, the range's own slopes harbor unique ecosystems adapted to dramatic moisture gradients.

Together, these features have shaped where Chileans live, what they grow, and how they interact with their environment. From the mining operations of the arid north to the wine valleys of the center to the dairy farms and forests of the south, the interplay between coastal mountains and interior valley defines Chilean geography.

As Chile confronts climate change, water scarcity, and sustainable development challenges, understanding and managing these landscapes becomes ever more critical. They represent not just geographic features, but the physical foundation of Chilean society. This foundation has supported human civilization for millennia and must continue to do so for generations to come.

The depiction of the eastern border of the Chilean Coastal Range is marked in yellow, and uncertain boundaries are marked with dots.