The Guatemalan Highlands: A Geological and Cultural Crossroads

The Guatemalan Highlands extend from the Pacific plains to the Petén lowlands, characterized by volcanic peaks, valleys, lakes, and Indigenous communities. Their dramatic landscapes are the result of millions of years of tectonic activity, which has shaped both the environment and human culture.

Tierras Altas: The Geological Foundation of Guatemala's Cultural Heritage

Stretching between the Pacific coastal plains and Guatemala's northern Petén lowlands, the Guatemalan Highlands are among Central America's most geologically complex and culturally significant regions. Known locally as "Tierras Altas," this mountainous terrain encompasses towering volcanic peaks, deep valleys, pristine highland lakes, and Indigenous communities whose traditions span millennia. The region's dramatic landscapes are the result of millions of years of tectonic activity, creating a natural laboratory where geological forces have shaped both the physical environment and human civilization.

Geological Foundation and Tectonic Setting

Plate Boundary Dynamics

The Guatemalan Highlands occupy a critical position along the boundary between the Caribbean Plate and the North American Plate, with additional influence from the Cocos Plate subduction zone to the south. This complex tectonic intersection has generated the mountain ranges, volcanic chains, and deep structural valleys that define the region's topography.

The ongoing convergence of these tectonic plates continues to shape the landscape through seismic activity and volcanic processes. The subduction of the Cocos Plate beneath the Caribbean Plate has created the Central American Volcanic Arc, which extends through the southern portion of the Highlands and includes some of Guatemala's most prominent volcanic peaks.

Mountain Systems

Two primary mountain ranges dominate the Guatemalan Highlands: the Sierra Madre de Chiapas in the south and the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes in the north. These ranges represent different geological histories and formation processes that have contributed to the region's topographic diversity.

The Sierra Madre de Chiapas extends into Guatemala from Mexico, forming the backbone of the southern Highlands. This range includes numerous volcanic peaks and reaches elevations exceeding 4,000 meters (13,120 feet). The Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, composed primarily of sedimentary rocks uplifted during regional mountain-building episodes, dominates the northern Highlands and contains Guatemala's highest non-volcanic peaks.

Between these major ranges lie numerous smaller mountain chains, volcanic complexes, and structural valleys, which create a complex mosaic of highland terrain. Elevations throughout the region typically range from 1,000 to 4,220 meters (3,280 to 13,845 feet), creating dramatic elevation gradients over relatively short distances.

Volcanic Landscape and Major Peaks

Central America's Highest Summit

Volcán Tajumulco stands as the crown jewel of the Guatemalan Highlands, rising to 4,220 meters (13,845 feet) to claim the title of Central America's highest peak. This stratovolcano, located near the Mexican border, represents the culmination of volcanic processes that have built much of the Highland landscape over millions of years.

Despite its imposing height, Tajumulco has remained relatively quiet historically, with no recorded eruptions during the colonial or modern periods. The volcano's massive edifice was constructed through repeated episodes of explosive and effusive activity, resulting in the layered deposits of lava flows, pyroclastic materials, and volcanic debris that comprise its current structure.

Active Volcanic Systems

The Guatemalan Highlands are home to several active volcanic systems that continue to shape the landscape and influence regional development patterns. Volcán de Fuego, standing at 3,763 meters (12,346 feet), maintains near-constant activity and ranks among Central America's most closely monitored volcanoes. Its frequent eruptions create spectacular displays while posing ongoing hazards to surrounding communities.

Volcán Acatenango, rising to 3,976 meters (13,045 feet), represents Fuego's larger but dormant neighbor. The contrast between these adjacent volcanoes illustrates the complex evolution of volcanic systems, in which the migration of magmatic activity over time creates chains of volcanic edifices with varying activity levels.

Other significant volcanic peaks include Volcán Agua at 3,670 meters (12,040 feet), which overlooks the colonial city of Antigua Guatemala, and the Volcán Atitlán complex, which forms part of the spectacular backdrop for Lake Atitlán.

Volcanic Hazards and Monitoring

The active volcanic systems within the Guatemalan Highlands generate various hazards that affect both local communities and regional infrastructure. Pyroclastic flows, volcanic ash, lahars, and volcanic gases pose ongoing threats that require sophisticated monitoring and emergency preparedness systems.

The Instituto Nacional de Sismología, Vulcanología, Meteorología e Hidrología (INSIVUMEH) maintains comprehensive monitoring networks across volcanic regions, using seismic stations, thermal cameras, gas sensors, and satellite imagery to monitor volcanic activity. These monitoring efforts have become increasingly critical as population growth brings more communities into proximity with active volcanic systems.

Lake Atitlán: A Volcanic Legacy

Formation and Geology

Lake Atitlán, often described as one of the world's most beautiful lakes, occupies a volcanic caldera formed approximately 84,000 years ago during one of the most explosive volcanic eruptions in Central American geological history. The Los Chocoyos eruption ejected an estimated 300 cubic kilometers (72 cubic miles) of volcanic material, creating the depression that now contains the lake.

The lake reaches maximum depths of approximately 340 meters (1,115 feet), making it Central America's deepest lake. Its waters are contained within steep volcanic walls that rise more than 1,500 meters (4,920 feet) above the lake surface, creating the dramatic setting for which Atitlán is renowned.

Three volcanic peaks—Atitlán, Tolimán, and San Pedro—rise directly from the lake's southern shore, creating a landscape where volcanic and lacustrine environments intersect. These volcanoes continue to influence the lake's chemistry and ecology through ongoing hydrothermal activity and weathering processes.

Ecological Significance

Lake Atitlán supports unique aquatic ecosystems that have evolved in isolation since the caldera's formation. The lake's deep, oligotrophic waters maintain distinct thermal layers, supporting endemic species that exist nowhere else on Earth.

However, the lake faces increasing environmental pressures from population growth, agricultural runoff, and climate change. Periodic algae blooms and water quality issues highlight the challenges of maintaining ecological balance in this iconic highland water body.

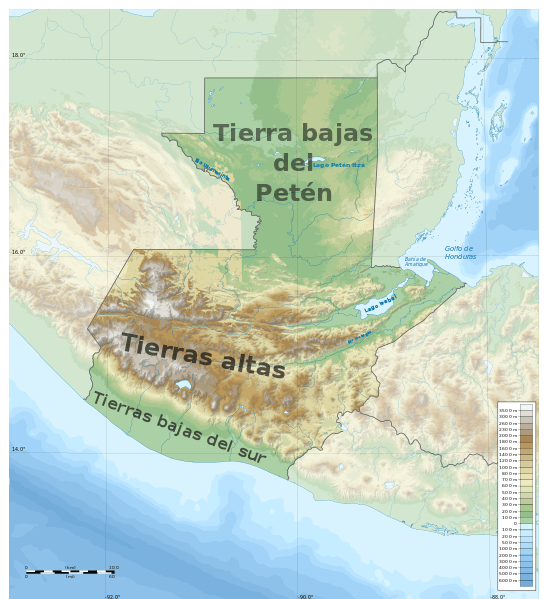

Map depicting the major geographic regions of Guatemala. The Guatemalan Highlands occupy the area labeled "Tierras Altas."

Cultural Heritage and Indigenous Communities

Maya Civilizations

The Guatemalan Highlands have served as the heartland of Maya civilization for over two millennia. Archaeological evidence indicates continuous human occupation dating back to the Pre-Classic period (2000 BCE - 250 CE), with major ceremonial centers and urban settlements developing throughout the Classic (250-900 CE) and Post-Classic (900-1500 CE) periods.

Major archaeological sites, such as Iximche, Mixco Viejo, and Zaculeu, preserve architectural and cultural remnants of the highland Maya kingdoms that controlled extensive territories and trade networks. These sites demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of astronomy, mathematics, agriculture, and urban planning that allowed complex societies to thrive in challenging mountain environments.

Contemporary Indigenous Communities

Modern Indigenous communities throughout the Guatemalan Highlands maintain direct cultural and linguistic connections to their Pre-Columbian ancestors. Major language groups include K'iche', Kaqchikel, Tz'utujil, Mam, Ixil, and Q'anjob'al, each preserving distinct traditions, social organizations, and relationships with the highland landscape.

These communities have developed sophisticated agricultural systems adapted to highland conditions, including terraced farming, crop rotation practices, and diverse cultivation strategies that maintain soil fertility on steep slopes. Traditional ecological knowledge accumulated over generations continues to inform contemporary conservation and sustainable development efforts.

Colonial Legacy

Spanish colonization, beginning in the 16th century, introduced new architectural styles, economic systems, and cultural influences that created the distinctive blend of Indigenous and European elements visible throughout the Highlands today. Cities like Antigua Guatemala preserve exceptional examples of colonial architecture while serving as regional centers where Indigenous and Hispanic cultures continue to interact.

Colonial period activities, particularly mining and plantation agriculture, significantly altered highland landscapes and established economic patterns that continue to influence regional development. The introduction of new crops, livestock, and land tenure systems brought about lasting changes in how highland communities interacted with their environment.

Economic Systems and Land Use

Agricultural Foundations

Agriculture remains the economic foundation for most highland communities, with farming systems adapted to the region's diverse elevation zones and microclimates. Traditional crops, including maize, beans, and squash, continue to provide subsistence security, while cash crops, such as coffee, vegetables, and flowers, generate income for market participation.

Coffee cultivation represents the most significant commercial agricultural activity in many highland areas. The combination of volcanic soils, favorable climate conditions, and elevation gradients creates ideal conditions for producing high-quality Arabica coffee that commands premium prices in international markets.

Highland agriculture continues to face ongoing challenges from climate variability, soil erosion, and market fluctuations. Many communities are adopting sustainable farming practices, organic certification programs, and cooperative marketing strategies to improve economic returns while protecting natural resources.

Economic Diversification

Beyond agriculture, highland communities are increasingly relying on a diverse range of economic activities, including artisanal production, tourism services, and wage labor in regional urban centers. Traditional textile production, wood carving, ceramics, and other handicrafts provide important sources of income while preserving cultural heritage.

Tourism has become increasingly important in areas with exceptional natural beauty or cultural attractions. Lake Atitlán, Antigua Guatemala, and various volcanic peaks attract significant numbers of domestic and international visitors, creating employment opportunities in hospitality, guiding, transportation, and related services.

Conservation Challenges and Initiatives

Environmental Pressures

The Guatemalan Highlands face mounting environmental pressures from population growth, agricultural expansion, and climate change. Deforestation rates remain high in many areas, driven by demands for agricultural land, fuelwood, and construction materials. Soil erosion on steep slopes threatens agricultural productivity and contributes to sedimentation of rivers and lakes.

Water resources are facing increasing stress from competing demands for domestic use, irrigation, and hydroelectric power generation. Climate change projections indicate potential shifts in precipitation patterns and temperature regimes that could significantly affect highland ecosystems and agricultural systems.

Protected Areas and Conservation Programs

Government agencies and non-governmental organizations have established numerous protected areas throughout the Guatemalan Highlands to conserve biodiversity and protect watershed resources. These include national parks, biosphere reserves, wildlife refuges, and private nature reserves that collectively preserve significant portions of highland ecosystems.

Conservation programs are increasingly recognizing the importance of working with Indigenous and local communities that possess traditional ecological knowledge and depend on natural resources for their livelihoods. Community-based conservation initiatives, payment-for-ecosystem-services programs, and sustainable development projects aim to strike a balance between conservation objectives and human needs.

Sustainable Development Initiatives

Various organizations promote sustainable development approaches that address economic needs while protecting natural resources and cultural heritage. These initiatives include ecotourism development, sustainable agriculture programs, renewable energy projects, and community-based natural resource management.

Success in achieving sustainable development depends on addressing underlying issues such as poverty, land tenure insecurity, limited access to education and healthcare, and weak institutional capacity. Integrated approaches that simultaneously address social, economic, and environmental challenges offer the greatest potential for long-term sustainability.

Scientific Research and Monitoring

Geological Studies

The Guatemalan Highlands are an important site for geological research on volcanism, tectonics, and mountain-building processes. Universities and research institutions conduct ongoing studies of volcanic hazards, earthquake risks, landslide susceptibility, and other geological phenomena that affect highland communities.

Paleoclimate research, using lake sediments, volcanic deposits, and other geological records, provides valuable insights into long-term environmental changes and helps predict future climate impacts. These studies contribute to understanding how highland ecosystems and human societies have responded to past environmental changes.

Ecological Research

Biological research in the Guatemalan Highlands focuses on understanding biodiversity patterns, ecosystem functioning, and conservation priorities. The region's elevation gradients and habitat diversity make it particularly valuable for studying how species and ecosystems respond to environmental variation.

Long-term ecological monitoring programs track changes in forest cover, species populations, and the overall health of ecosystems. These studies provide essential data for evaluating the effectiveness of conservation efforts and identifying emerging environmental threats.

Regional Significance and Future Prospects

Cultural and Natural Heritage

The Guatemalan Highlands represent one of the world's most significant examples of a landscape where natural and cultural heritage are intimately connected. The region's geological processes have created the physical foundation for diverse ecosystems and human societies, while Indigenous communities have developed sophisticated systems for living sustainably in challenging mountain environments.

This heritage faces increasing pressures from globalization, economic development, and environmental change. Protecting the region's natural and cultural values requires an integrated approach that supports both conservation objectives and community development needs.

Climate Change Implications

Climate change poses significant challenges for highland ecosystems and communities. Temperature increases may alter the elevation ranges suitable for different species and crops, while changes in precipitation patterns could affect water resources and agricultural productivity.

Adaptation strategies must consider both immediate needs and long-term sustainability. Building resilience in highland communities requires strengthening local institutions, diversifying economic opportunities, protecting natural resources, and maintaining traditional knowledge systems that have enabled successful adaptation to environmental variability over generations.

Conclusion

The Guatemalan Highlands represent a remarkable convergence of geological, biological, and cultural processes that have created one of Central America's most distinctive and significant regions. The ongoing interaction between tectonic forces, volcanic activity, and human societies continues to shape landscapes and communities in ways that reflect millions of years of geological evolution and thousands of years of cultural development.

Understanding and protecting this heritage requires recognizing the complex relationships between natural processes and human activities that have shaped the Highlands' contemporary character. The region's volcanic peaks, highland lakes, Indigenous communities, and colonial cities constitute an integrated system that must be conserved and managed as an interconnected whole rather than as isolated components.

The future of the Guatemalan Highlands depends on successfully balancing development pressures with conservation needs, supporting Indigenous communities while protecting cultural heritage, and adapting to environmental changes while maintaining the essential characteristics that make this region unique. Achieving these goals requires continued scientific research, effective conservation programs, sustainable development initiatives, and recognition of the fundamental connections between geological processes, ecological systems, and human communities that define the Highland experience.