El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar: Where Fire Meets Sand

In northwestern Mexico, where the Sonoran Desert meets the Gulf of California, the El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar features volcanic craters, shifting dunes, and resilient desert ecosystems. Spanning Sonora and Baja California, it showcases Earth's geological power and ecological resilience.

The Pinacate Shield: Life Among Ancient Volcanoes and Living Dunes

In the remote borderlands of northwestern Mexico, where the Sonoran Desert meets the Gulf of California, lies one of Earth's most dramatic landscapes—the El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve. This UNESCO World Heritage Site presents a stark yet magnificent tableau where volcanic craters pierce ancient lava flows, towering sand dunes shift with desert winds, and life flourishes in seemingly impossible conditions. Spanning 714,566 hectares (1,765,700 acres) across Sonora and extending into Baja California, this extraordinary reserve showcases the raw power of geological forces and the remarkable resilience of desert ecosystems.

A Land Forged by Fire: The Pinacate Volcanic Shield

Geological Origins and Formation

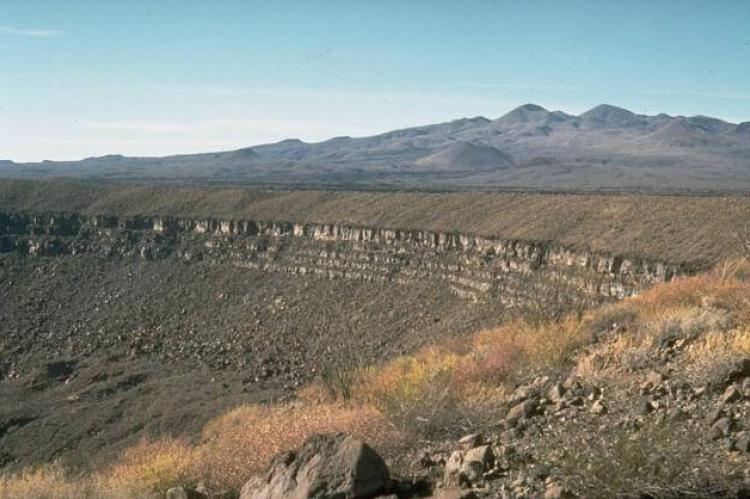

The Pinacate Shield represents one of North America's most complete and accessible volcanic landscapes. This dormant shield volcano, covering approximately 200,000 hectares (494,000 acres), began forming roughly 4 million years ago through successive eruptions that built layer upon layer of basaltic lava flows.

The shield's most dramatic features are its ten enormous maar craters—circular depressions formed by explosive steam eruptions when rising magma encountered groundwater. These nearly perfect circles, ranging from 1 to 1.4 kilometers (0.6 to 0.9 miles) in diameter, create an otherworldly landscape that has served as a training ground for NASA astronauts preparing for lunar missions.

The Three Sentinels

Three prominent peaks dominate the Pinacate Shield, each representing a different phase of volcanic activity:

Cerro del Pinacate: The highest peak at 1,206 meters (3,957 feet), this summit offers panoramic views across the entire reserve and into the Gulf of California.

Carnegie Peak: Named after the Carnegie Institution, this peak reaches 1,189 meters (3,901 feet) and showcases classic shield volcano morphology.

Cerro Medio: The "middle peak" at 1,129 meters (3,704 feet), positioned between its taller companions, demonstrates the shield's complex eruptive history.

Volcanic Landscapes and Lava Fields

The Pinacate Shield presents a museum of volcanic phenomena. Vast aa and pahoehoe lava flows create textured landscapes ranging from ropey, undulating surfaces to sharp, clinker-like formations. These flows, some extending for kilometers, tell the story of different eruption styles and cooling conditions.

Desert pavement—flat surfaces covered with closely packed volcanic rocks—creates natural mosaics across much of the shield. These pavements, formed over thousands of years through freeze-thaw cycles and wind action, support specialized plant communities adapted to thin soil layers and extreme temperature variations.

Volcanic tubes and caves punctuate the lava flows, creating subterranean habitats that maintain more moderate temperatures and humidity levels than the surface. These refugia support unique communities of bats, arthropods, and adapted plant species.

The Gran Desierto de Altar: North America's Sahara

A Sea of Living Sand

West of the Pinacate Shield stretches the Gran Desierto de Altar, North America's largest active dune system. This dynamic landscape covers approximately 5,600 square kilometers (2,160 square miles) and contains an estimated 60 cubic kilometers (14 cubic miles) of sand.

The dune field represents multiple sand sources and transport mechanisms. Sediments from the Colorado River Delta, carried by prevailing winds, combine with locally derived materials from weathered granitic mountains and ancient lake beds. This mixture creates dunes of varying composition and color, from golden quartz grains to darker volcanic particles.

Dune Types and Dynamics

The Gran Desierto hosts several distinct dune types, each responding differently to wind patterns and sediment supply:

Star Dunes: Multi-armed giants reaching heights of 200 meters (650 feet), these complex formations result from multidirectional winds and can remain stationary for centuries.

Linear Dunes: Parallel ridges extending for kilometers, aligned with prevailing wind directions and migrating slowly across the landscape.

Barchan Dunes: Crescent-shaped formations that migrate steadily downwind, creating moving obstacles for desert vegetation.

Erg Systems: Vast sand seas where individual dunes merge into continuous fields, creating some of the most challenging terrain in North America.

Granite Islands in a Sand Sea

Rising from the dune fields like islands, granite massifs reach elevations of 300 to 650 meters (980 to 2,130 feet) above sea level. These ancient intrusions, exposed by millions of years of erosion, create vertical habitat gradients that support distinct plant and animal communities.

Sierra del Rosario: The most prominent massif, featuring steep-walled canyons and natural water catchments that support relict plant communities.

Sierra de los Tanques: Named for its natural rock pools, this range provides crucial water sources during dry periods.

Tinajas Altas: Literally "high tanks," this range contains some of the region's most reliable water sources, historically crucial for both wildlife and human travelers.

Biodiversity in Extremis

Botanical Adaptations

The reserve supports over 560 species of vascular plants, representing one of the most diverse desert floras in North America. This botanical richness reflects the region's complex topography, varied substrates, and microclimatic diversity.

Columnar Cacti: Several species create vertical forests in suitable habitats, including organ pipe cactus (Stenocereus thurberi), Mexican giant cardon (Pachycereus pringlei), and senita cactus (Lophocereus schottii).

Desert Ironwood (Olneya tesota): These long-lived trees, some over 800 years old, create crucial habitat structure and nurse plant conditions for numerous other species.

Palo Verde Trees: Multiple species provide the primary canopy in desert washes, their green bark continuing photosynthesis when leaves are absent during drought.

Desert Broom (Baccharis sarothroides): Pioneer species that colonizes disturbed areas and provides crucial erosion control on dune margins.

Endemic Species: Several plants exist nowhere else on Earth, including Abutilon palmeri and specialized varieties of ghost plant (Graptopetalum paraguayense).

Fauna: Masters of Desert Survival

The reserve's animal communities demonstrate remarkable adaptations to extreme heat, water scarcity, and challenging terrain.

Large Mammals

Sonoran Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana sonoriensis): This critically endangered subspecies numbers fewer than 300 individuals. These remarkable animals can survive without drinking water, obtaining all moisture from their plant diet, and can reach speeds of 95 kilometers per hour (59 mph).

Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis mexicana): Perfectly adapted to rocky terrain, these sheep can scale near-vertical cliffs and survive on minimal water. Their populations use the granite massifs as refugia during extreme weather.

Mountain Lions (Puma concolor): The apex predators maintain territories covering hundreds of square kilometers (square miles), following prey animals and seasonal water sources.

Small Mammals and Desert Specialists

Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis): These nocturnal hunters possess oversized ears for heat dissipation and acute hearing for locating prey in sandy substrates.

Kangaroo Rats: Multiple species have evolved extreme water conservation, producing concentrated urine and dry feces while obtaining all moisture from their seed diet.

Desert Pocket Mouse (Chaetodipus intermedius): Specialized for dune habitats, these mice can survive temperature extremes and navigate shifting dune systems.

Reptilian Diversity

With over 40 reptile species, the reserve represents one of North America's richest herpetological communities:

Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii): Long-lived reptiles that can survive over 80 years, storing water in their bladders and entering extended dormancy during extreme conditions.

Gila Monster (Heloderma suspectum): North America's largest venomous lizard, perfectly adapted to desert conditions with efficient metabolism and water storage capabilities.

Sidewinder Rattlesnake (Crotalus cerastes): Specialized for dune locomotion, these snakes move using a distinctive sidewinding motion that minimizes contact with hot sand.

Chuckwalla (Sauromalus ater): Large herbivorous lizards that wedge themselves into rock crevices for protection, inflating their bodies to make extraction impossible.

Avian Communities

Over 200 bird species utilize the reserve's diverse habitats, from desert specialists to seasonal migrants:

Cactus Wren (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus): The largest North American wren, these birds build multiple nests in cholla cacti and have adapted to desert heat through behavioral modifications.

Gila Woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis): Essential ecosystem engineers that excavate nest cavities in saguaro cacti, which are later used by numerous other species.

Costa's Hummingbird (Calypte costae): Specialized nectar feeders that time their breeding to coincide with desert wildflower blooms.

Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos): Apex avian predators that nest on granite cliff faces and hunt across vast desert territories.

Marine and Coastal Ecosystems

The Gulf of California Interface

The eastern boundary of the reserve meets the Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez), creating a unique interface between terrestrial and marine ecosystems. This transition zone supports specialized communities adapted to both desert and coastal conditions.

Critical Marine Species

Vaquita (Phocoena sinus): The world's most endangered cetacean, with fewer than 30 individuals remaining. These small porpoises inhabit only the upper Gulf of California and face extinction due to fishing activities.

Totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi): Large fish that can reach 100 kilograms (220 pounds) and live over 20 years. Illegal fishing for their swim bladders has driven them to endangered status.

Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas): Important nesting beaches occur along the reserve's coastline, supporting regional populations of this recovering species.

Coastal Habitats

Tidal Flats: Extensive mudflats exposed during low tides support millions of migrating shorebirds and serve as nurseries for numerous fish species.

Salt Marshes: Limited but crucial wetland habitats that support specialized plant communities and provide feeding areas for numerous bird species.

Rocky Intertidal: Areas where granite massifs meet the sea create complex three-dimensional habitats supporting diverse marine communities.

Cultural and Archaeological Significance

Indigenous Heritage

The reserve contains evidence of human occupation spanning over 20,000 years. The Tohono O'odham, Seri, and Cocopah peoples developed sophisticated desert survival strategies and maintain spiritual connections to the landscape.

Ancient shell middens along the coast indicate extensive use of marine resources, while petroglyphs and pictographs in granite canyons record thousands of years of human presence. Traditional ecological knowledge from these communities continues to inform modern conservation efforts.

Scientific Research Station

The reserve serves as a natural laboratory for desert ecology, climate change research, and conservation biology. Long-term monitoring programs track ecosystem responses to climate variability, while international research collaborations advance understanding of arid ecosystem dynamics.

Conservation Challenges and Management

Climate Change Impacts

Rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns threaten desert species already living near their physiological limits. Extended drought periods stress vegetation communities, while extreme heat events can exceed tolerance thresholds for some species.

Sea level rise and increased storm intensity affect coastal habitats, while changes in Gulf of California oceanography impact marine ecosystems. These changes require adaptive management strategies and enhanced habitat connectivity.

Border Security and Habitat Fragmentation

The reserve's location along the U.S.-Mexico border creates unique management challenges. Security infrastructure can fragment wildlife movement corridors, while human activity associated with border crossing impacts pristine desert areas.

International cooperation between Mexican and U.S. agencies becomes crucial for maintaining ecosystem integrity and protecting transboundary species populations.

Invasive Species Management

Non-native plants like buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) threaten native plant communities, while feral animals impact endemic species. Control efforts require sustained commitment and international coordination.

Sustainable Tourism Development

Growing international recognition brings increased visitation pressure. Balancing access with ecosystem protection requires careful planning, visitor education, and infrastructure development that minimizes environmental impact.

Research and Scientific Significance

Astrobiology and Space Research

The reserve's volcanic landscapes provide Earth analogs for Mars and other planetary surfaces. NASA continues to use the area for astronaut training and robotic mission testing, contributing to our understanding of life in extreme environments.

Climate Change Research

Long-term ecological monitoring provides crucial data on desert ecosystem responses to climate variability. The reserve serves as a sentinel site for detecting climate change impacts in arid regions worldwide.

Conservation Biology

Ongoing research on endangered species recovery, habitat connectivity, and ecosystem restoration contributes to global conservation science. The reserve's management strategies inform conservation efforts throughout the Sonoran Desert region.

Conclusion: A Testament to Life's Tenacity

The El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve stands as one of Earth's most remarkable natural laboratories—a place where volcanic fire has created the stage for life's most dramatic adaptations to extreme conditions. From the perfect circles of ancient maar craters to the shifting sands of North America's largest dune system, from tiny desert pupfish surviving in isolated pools to magnificent pronghorn racing across volcanic plains, this landscape tells stories of resilience, adaptation, and survival.

As climate change intensifies and human pressures mount, the reserve's importance extends far beyond its boundaries. It serves as a refuge for endangered species, a natural laboratory for understanding ecosystem dynamics, and an inspiration for conservation efforts worldwide. The lessons learned here—about adaptation, sustainability, and the intricate relationships between geology, climate, and life—become increasingly relevant as we face an uncertain environmental future.

In this land where fire meets sand, where ancient volcanoes create islands of life in seas of dunes, where the smallest creatures demonstrate the greatest adaptations, we find both humility and hope. The El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve reminds us that life, given time and space, finds ways to flourish even in Earth's most challenging environments. It stands as a monument to the power of protection, the value of scientific research, and the enduring beauty of our planet's most extraordinary places.

This remarkable landscape continues to evolve, its dunes shifting with seasonal winds, its ecosystems responding to changing conditions, its species adapting to new challenges. As we work to understand and protect this unique corner of our planet, we participate in a story that began millions of years ago with volcanic eruptions and continues today with every sunrise over the Gran Desierto's golden dunes and every sunset behind the Pinacate's ancient peaks.