The West Indies: Arc of Islands Between Two Seas

The West Indies forms a spectacular crescent-shaped archipelago of over 7,000 islands, cays, and islets that separates the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. This geologically complex island system represents one of Earth's most biodiverse and culturally dynamic regions.

The West Indies: Caribbean Archipelago of Volcanoes, Coral, and Culture

Stretching across more than 3,000 kilometers (1,865 miles) of turquoise waters from the Florida Keys to the northern coast of Venezuela, the West Indies forms a spectacular crescent-shaped archipelago of over 7,000 islands, cays, and islets that separates the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. This geologically complex island system—known interchangeably as the Caribbean Islands or simply the Caribbean—represents one of Earth's most biodiverse and culturally dynamic regions, where active volcanoes rise alongside ancient limestone plateaus, where coral reefs teem with marine life, and where the cultural legacies of Indigenous peoples, European colonizers, and African diaspora communities have fused into vibrant societies found nowhere else on the planet. From Cuba's revolutionary fervor to Trinidad's Carnival rhythms, from the volcanic peaks of Martinique to the crystalline shallows of the Bahamas, the West Indies embodies a unique synthesis of natural splendor and human creativity forged across centuries of migration, conquest, resistance, and adaptation.

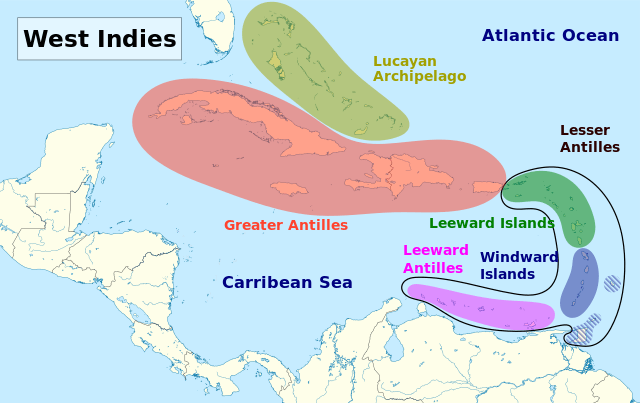

Map depicting the island groups of the West Indies.

Geography and Geological Origins

The West Indies comprises three distinct archipelagos, each with its own geological history and character: the Greater Antilles, the Lesser Antilles, and the Lucayan Archipelago. Together, these island groups span approximately 235,000 square kilometers (91,000 square miles) of land area surrounded by more than 2.75 million square kilometers (1.06 million square miles) of territorial seas.

The Greater Antilles: Ancient Fragments

The Greater Antilles—comprising Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola (shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, and the Cayman Islands—contains nearly 90% of the West Indies' total land area and includes the Caribbean's four largest islands. These islands are geologically the oldest in the region, originating as volcanic island arcs near present-day Central America during the Late Cretaceous period (approximately 70-100 million years ago). Tectonic forces gradually pushed this "Proto-Antilles" eastward until it collided with the Bahama Platform of the North American Plate roughly 56 million years ago during the late Paleocene epoch.

Cuba, the Caribbean's largest island at 109,884 square kilometers (42,426 square miles), consists predominantly of flat limestone plains. Approximately 65-70% of the island is karst limestone riddled with caves, sinkholes, and underground rivers—terrain formed over millions of years as mildly acidic rainwater dissolved the calcium carbonate bedrock. The island's oldest rocks are metamorphosed graywacke, argillite, and volcanic flows dating to the Jurassic period. Despite Cuba's generally flat topography, with median elevations around 90 meters (295 feet), the Sierra Maestra range in the southeast reaches 1,974 meters (6,476 feet) at Pico Turquino, Cuba's highest point.

Jamaica's Blue Mountains, formed from ancient volcanic activity and later uplifted, rise to 2,256 meters (7,402 feet) at Blue Mountain Peak. The island's rugged interior contrasts sharply with low coastal plains, creating dramatic elevation changes across relatively short distances. Hispaniola features the Caribbean's tallest peak, Pico Duarte in the Dominican Republic, reaching 3,098 meters (10,164 feet). Puerto Rico's Cordillera Central tops out at 1,338 meters (4,390 feet) at Cerro de Punta.

These mountainous landscapes create microclimates supporting diverse ecosystems, from coastal mangroves and dry forests to cloud forests at higher elevations. The Greater Antilles have been continuously exposed above sea level for at least 40-66 million years, allowing unique flora and fauna to evolve in relative isolation.

The Lesser Antilles: Young Volcanic Arc

The Lesser Antilles form a 750-kilometer (466-mile) arc of smaller islands stretching from the Virgin Islands southeast to Grenada, then curving west toward the Venezuelan coast. This archipelago consists of two parallel island chains reflecting different geological processes. The inner arc—running from Saba through St. Kitts, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Grenada—comprises active volcanic islands formed as the Atlantic oceanic plate subducts beneath the Caribbean Plate. Most of these islands emerged within the past 20 million years, making them geological youngsters compared to the ancient Greater Antilles.

The volcanic inner arc contains 19 active volcanoes, several of which have erupted catastrophically in historical times. Mount Pelée on Martinique famously destroyed the city of St-Pierre in 1902, killing approximately 30,000 people. La Soufrière on St. Vincent erupted violently in 1902 and again in 1979, while Montserrat's Soufrière Hills volcano began erupting in 1995 and buried the capital, Plymouth, under volcanic ash and pyroclastic flows. These volcanoes create dramatic mountainous landscapes with fertile volcanic soils that support lush tropical rainforests.

The outer arc—including Anguilla, Antigua, Barbados, and the eastern portions of Guadeloupe—consists of older, low-lying limestone islands overlying ancient volcanic or crystalline basement rocks. These islands represent former volcanic peaks that have eroded and been covered by limestone deposited during periods when sea levels were higher. Barbados, the easternmost Caribbean island, reaches only 340 meters (1,115 feet) at its highest point and features gently rolling limestone hills rather than dramatic peaks.

The southernmost islands of the Lesser Antilles—Trinidad and Tobago, and the Dutch ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao)—sit on the South American continental shelf and represent geologically distinct formations closely related to the South American mainland rather than the Caribbean island arc.

The Lucayan Archipelago: Limestone Platforms

The Lucayan Archipelago, comprising the Commonwealth of the Bahamas (more than 700 islands and 2,400 cays) and the British Overseas Territory of Turks and Caicos Islands, lies in the Atlantic Ocean north of Cuba and east of Florida. These low-lying coral and limestone islands rest atop the Bahama Platform, a vast carbonate bank formed over millions of years by marine sediments deposited on the seafloor. The platform consists of limestone deposits 6-10 kilometers (3.7-6.2 miles) thick, dating to the Jurassic period.

Unlike the volcanic islands farther south, the Lucayan islands formed through the gradual accumulation of calcium carbonate from marine organisms and coral reefs, followed by deposition of wind-blown sand during periods of lower sea level. The islands are exceptionally flat, with the highest natural point in the entire Bahamas reaching only 63 meters (207 feet) on Cat Island. This limestone composition has created remarkably clear waters—visibility exceeding 61 meters (200 feet) in some areas—and supports approximately 5% of the world's coral reefs.

The islands' permeable limestone structure means there are no rivers or permanent streams. Fresh water occurs in underground lenses floating atop denser saltwater, accessed through blue holes—circular sinkholes that penetrate the limestone to reveal crystal-clear pools that connect to extensive underwater cave systems.

Climate and Oceanography

The West Indies experiences a tropical maritime climate moderated by trade winds and ocean currents. Daily maximum temperatures across most islands range from the mid-80s°F (upper 20s°C) in winter (December-April) to the upper 80s°F (low 30s°C) in summer (May-November), with nighttime temperatures typically 10°F (6°C) cooler. However, the region's complex topography creates significant microclimatic variation—windward mountain slopes receive substantially more rainfall than leeward coasts, and higher elevations experience cooler temperatures than coastal areas.

Annual rainfall varies dramatically across the region, from less than 500 millimeters (20 inches) in the arid ABC islands off Venezuela to more than 5,000 millimeters (197 inches) on the highest peaks of Dominica and other mountainous islands. Most islands experience distinct wet and dry seasons, with the wet season extending from May through November, coinciding with the Atlantic hurricane season.

Hurricanes pose the most significant climatic threat to the West Indies. These powerful tropical cyclones form over warm Atlantic waters and frequently track through the Caribbean, bringing destructive winds exceeding 250 kilometers per hour (155 miles per hour), torrential rainfall, and storm surge flooding. The hurricane season peaks from August through October, though storms can occur from June through November.

The Caribbean Sea and adjacent Atlantic waters maintain average temperatures of 24-28°C (75-82°F), supporting the coral reef ecosystems that fringe many islands. The North Equatorial Current and Guiana Current create a westward flow through the Caribbean Basin, with water exiting through the Yucatan Channel into the Gulf of Mexico and contributing to the Gulf Stream system. This circulation renews the Caribbean's water volume and distributes nutrients and marine larvae throughout the region.

Biodiversity and Endemic Species

The West Indies represents a biodiversity hotspot of extraordinary significance. The region's insular geography—thousands of islands separated by ocean barriers—combined with diverse habitats ranging from coral reefs to cloud forests, has generated exceptional levels of endemism. An estimated 72% of the West Indies' plant species and 60% of vertebrate species are endemic, found nowhere else on Earth.

The islands support over 13,000 plant species, including numerous palms, orchids, and mahogany trees. Cuba alone harbors more than 6,000 plant species, roughly half of them endemic. The Puerto Rican parrot, Jamaican boa, Cuban crocodile, Hispaniolan solenodon, and countless other species evolved in isolation on individual islands, making them particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and introduced species.

Marine biodiversity is equally impressive. Caribbean coral reefs, though covering only 8% of the world's reef area, support more than 1,000 coral species and over 1,500 fish species. The reefs provide essential ecosystem services, including coastal protection, fisheries habitat, and tourism revenue, while harboring species found only in Caribbean waters.

However, West Indian ecosystems face severe threats. Deforestation, particularly during the colonial sugar plantation era, eliminated most of the original forest cover. Today, less than 10% of the pre-Columbian forest remains. Coral reefs have declined dramatically due to warming waters, disease, pollution, and overfishing. Many endemic species teeter on the edge of extinction, including the critically endangered Hispaniolan hutia, the Caribbean monk seal (declared extinct in 2008), and numerous parrot and iguana species.

A History Written in Migration and Conquest

Archaeological evidence suggests human settlement of the West Indies dates to at least 6,000 BCE, with the Greater Antilles showing occupation possibly as early as 7,000 years ago. Multiple waves of migration from South and Central America brought diverse Indigenous cultures to the islands. By the time of European contact, the major Indigenous groups included the Taíno, who dominated the Greater Antilles, the Bahamas, and parts of the Lesser Antilles; the Island Caribs (Kalinago), who occupied most of the Lesser Antilles; and various groups on Trinidad closely related to South American peoples.

Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492 initiated a catastrophic transformation. Though Columbus died believing he had reached Asia (hence "Indies"), Spanish colonization brought devastating epidemics, forced labor, and violence that decimated Indigenous populations. Within a century, the Taíno and most other Indigenous Caribbean peoples had virtually disappeared, victims of disease, enslavement, and warfare. Small communities of Kalinago people survived in the Lesser Antilles, with descendants still living in Dominica and St. Vincent.

The colonial period transformed the West Indies into a geopolitical chessboard where European powers competed for dominance. Spain initially controlled the Greater Antilles and key islands of the Lesser Antilles. Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark gradually established footholds, particularly in the Lesser Antilles, where smaller islands were easier to seize and defend. By the 17th and 18th centuries, the region had fragmented into a complex patchwork of colonial possessions that frequently changed hands through warfare, treaties, and purchases.

The sugar plantation economy, beginning in earnest in the mid-17th century, drove the massive forced migration of enslaved Africans to the Caribbean. Between 1500 and 1870, an estimated 4-5 million enslaved Africans were transported to the West Indies—representing roughly 40% of all enslaved people brought to the Americas. These individuals and their descendants formed the demographic and cultural foundation of modern West Indian societies, contributing African musical traditions, religious practices, agricultural knowledge, and languages that fused with European and surviving Indigenous elements to create unique Caribbean cultures.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) marked a watershed moment—enslaved people successfully overthrew the French colonial regime and established the first Black republic and the first nation in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery permanently. This revolution sent shockwaves through colonial powers and inspired resistance movements throughout the Americas.

Contemporary Political Geography

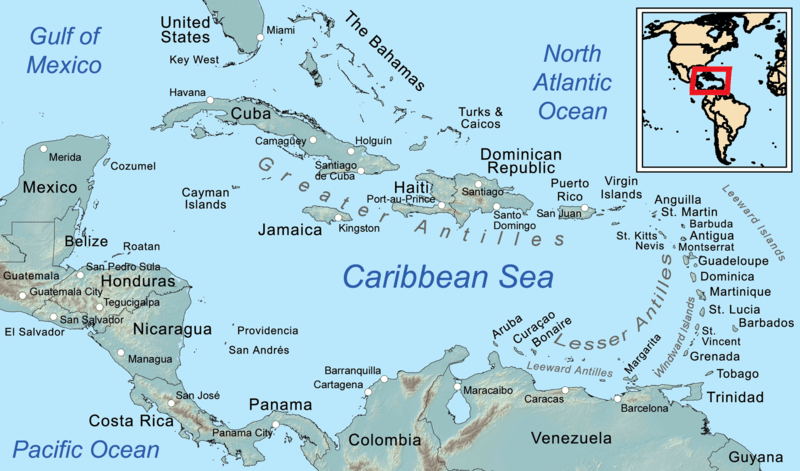

Today, the West Indies comprises 13 independent countries and 18 dependent territories, reflecting the region's complex colonial legacy. Independent nations include Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, the Bahamas, Barbados, St. Lucia, Grenada, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, and St. Kitts and Nevis. Dependent territories include Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (United States); Martinique and Guadeloupe (France); Aruba, Curaçao, and other Dutch islands (Kingdom of the Netherlands); and various British Overseas Territories, including the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos, and Anguilla.

This political fragmentation creates both challenges and opportunities. Small island nations face economic constraints, limited resources, vulnerability to natural disasters, and difficulties achieving economies of scale. However, regional cooperation through organizations like CARICOM (Caribbean Community) facilitates economic integration, policy coordination, and collective negotiation in international forums.

Cultural Vibrancy and Global Influence

Despite representing less than 0.5% of the global population, the West Indies has exerted an outsized cultural influence. Caribbean music genres, including reggae (Jamaica), calypso and soca (Trinidad), merengue and bachata (Dominican Republic), salsa (Cuba and Puerto Rico), and dancehall, have shaped global popular music. Bob Marley became one of the 20th century's most influential musicians, while countless other Caribbean artists have achieved international recognition.

Caribbean literature, exemplified by authors such as Derek Walcott (St. Lucia), V.S. Naipaul (Trinidad), and Jamaica Kincaid (Antigua), has won Nobel Prizes and has shaped postcolonial literary discourse. The region's Carnival celebrations—particularly Trinidad's—attract millions of participants and have inspired similar festivals globally. Caribbean cuisine, blending Indigenous, African, European, South Asian, and Chinese influences, has achieved worldwide popularity.

The West Indies also produced global sporting excellence, particularly in cricket, where the West Indies team dominated international competition through the 1970s-1990s, and in track and field, where sprinters from Jamaica and other islands regularly win Olympic medals.

An Arc Across Azure Waters

The West Indies remains a region of stunning natural beauty and remarkable human diversity. From the mist-shrouded peaks of Dominica's rainforests to the white-sand beaches of Antigua, from the vibrant streets of Havana to the coral gardens surrounding Bonaire, these islands offer landscapes and experiences found nowhere else on Earth. While facing challenges including climate change, economic vulnerability, and ecological degradation, the West Indies continues evolving, its people drawing on deep wells of creativity, resilience, and cultural vitality to forge futures worthy of this extraordinary arc of islands between two seas.

Map depicting the regions of the Caribbean.