The Maipo River: Lifeline of Central Chile

The Maipo River flows from the Andes to the Pacific Ocean, providing much of Santiago's freshwater supply. The river's basin contains more than 800 glaciers that serve as critical water storage during dry summer months. Climate change has driven dramatic glacier retreat, threatening water security.

Santiago's Lifeline: Climate Change and the Future of the Maipo River

Cascading down from the western slopes of Maipo Volcano in the High Andes, the Maipo River flows approximately 250 kilometers (155 miles) through the heart of Chile's most populous region before emptying into the Pacific Ocean at Llolleo. This majestic river, whose name derives from the Mapudungun words "maipun," meaning "work the land, plow," defines the main hydrographic basin of the Santiago Metropolitan Region and sustains nearly 80% of Santiago's freshwater supply—serving seven million inhabitants in Chile's capital city. The Maipo basin encompasses approximately 15,304 square kilometers (5,909 square miles) across the Santiago Metropolitan and Valparaíso regions, supporting agriculture, industry, and urban populations that comprise nearly half of Chile's GDP. Yet this vital river system faces mounting pressures from climate change, glacier retreat, prolonged drought, and growing demand, all of which threaten the water security of millions who depend on its life-giving flows.

Geographic Course and Tributaries

The Maipo River originates at Los Nacimientos ("The Birthplaces") on the western slope of Maipo Volcano at approximately 3,135 meters (10,285 feet) above sea level. From its source, the river flows northwest through the dramatic Cajón del Maipo—a deep Andean canyon popular for outdoor recreation, including whitewater rafting on Class III and IV rapids.

In its upper course, the river receives three major glacier-fed tributaries: the El Volcán River, the Yeso River, and the Colorado River. These tributaries significantly augment the Maipo's flow, particularly during spring and summer months when snowmelt and ice melt reach their peak.

After flowing approximately 110 kilometers (68 miles), the Maipo emerges from the Andes south of Puente Alto at an elevation near 800 meters (2,625 feet). Here it enters the wide Maipo Valley, where the river's alluvial deposits have created exceptionally fertile soils supporting one of Chile's most celebrated wine-producing regions.

As the river flows westward, it passes near Santiago before receiving the Mapocho River—which flows directly through the capital—as a right tributary near Talagante. After crossing through the coastal mountain range, the Maipo reaches Llolleo, where it flows into the Pacific Ocean.

The Glacial Crisis: Retreating Ice and Shrinking Water Supply

The Maipo River basin contains more than 800 glaciers covering approximately 378 square kilometers (146 square miles) as of 2000. These high-elevation ice masses, ranging from 3,500 to 5,800 meters (11,480 to 19,030 feet) above sea level, serve as critical water storage that releases meltwater during dry summer months when precipitation is minimal and demand peaks.

Research paints an alarming picture of rapid glacier retreat. Between 1955 and 2016, glacier volume in the Maipo basin decreased by one-fifth, from 18.6 to 14.9 cubic kilometers (from 4.5 to 3.6 cubic miles). The glacier area declined by 38%, from 558 to 347 square kilometers (215 to 134 square miles). The total mass loss between 1955 and 2013 reached 2.43 gigatons.

Climate change drives this retreat through rising temperatures and decreased precipitation. Air temperature increased approximately 0.25°C per decade between 1979 and 2006, while rainfall decreased by 7.1%. The prolonged mega-drought affecting central Chile since 2010 has accelerated glacier thinning rates.

Scientists predict a 40% drop in water balance by 2070, drastically shrinking the water supply. Even if climate change were to cease entirely, glaciers would continue retreating toward a new equilibrium, with projections suggesting glacier runoff could fall to 78% of historical averages. This ongoing retreat would significantly reduce the basin's drought-mitigation capacity, precisely when climate change makes droughts more frequent and severe.

Water Supply for Seven Million People

The Maipo basin provides approximately 70-80% of the municipal water supply for Santiago and over seven million inhabitants. This dependence on a single river system creates significant vulnerability as climate change, glacier retreat, and prolonged drought reduce available water.

During summer months when rainfall is negligible, the river's flow depends heavily on snowmelt and glacier melt from high-elevation sources. Approximately 60% of basin water is used for agriculture—primarily irrigating vineyards and orchards in the fertile Maipo Valley—while 35% serves drinking and sanitation needs, with the remainder supporting industry, including hydroelectric generation.

The El Yeso Reservoir in the upper basin stores water for Santiago's use, while several hydroelectric facilities generate electricity from the river's flow. However, water management becomes increasingly challenging during drought years when decreased precipitation and reduced glacier melt shrink available supplies while demand remains high.

Conservation Efforts and the Santiago Water Fund

Recognition of the Maipo watershed's critical importance has spurred innovative conservation initiatives. The Nature Conservancy, with support from HSBC, is creating the Santiago Water Fund to protect wetlands and native vegetation in the Maipo watershed, improving water quality for nature and people.

The Santiago Water Fund will restore High Andean wetlands, forests, and river-side vegetation to improve the quality and quantity of water reaching Santiago's inhabitants. The initiative addresses the reality that less than 5% of the Maipo watershed is under official protection, and that there is no formal governance or management structure for the watershed.

By protecting and restoring natural systems that filter water, reduce erosion, regulate streamflow, and maintain biodiversity, the Water Fund aims to create more resilient water sources in the face of climate change. The watershed faces mounting pressures from urban expansion, agricultural intensification, mining activities, and climate change, all of which threaten water quantity, quality, and ecosystem health.

Recreation and Tourism

The Cajón del Maipo has become one of Chile's premier outdoor recreation destinations, easily accessible from Santiago. The canyon offers spectacular Andean scenery, snow-capped peaks, and opportunities for hiking, mountain biking, horseback riding, and climbing.

Whitewater rafting on the Maipo River attracts thousands of visitors annually, with outfitters guiding rafters through exciting rapids during the spring and summer high-water season. The Embalse El Yeso (El Yeso Reservoir), located approximately 90 kilometers (56 miles) southeast of Santiago, has become a popular destination for day trips and photography, with turquoise waters surrounded by dramatic mountain peaks.

Hot springs, hiking trails, and opportunities for wildlife observation, including Andean condors (Vultur gryphus) and guanacos (Lama guanicoe), attract nature enthusiasts. The canyon also hosts the Refugio Animal Cascada, a rehabilitation center for native fauna that educates visitors about Chilean biodiversity.

The Path Forward

The Maipo River stands at a critical juncture. For nearly five centuries, the river has provided life-giving water for agriculture and urban development. Yet the confluence of climate change, glacier retreat, prolonged drought, and growing demand threatens the sustainability of current water use patterns.

The glaciers feeding the Maipo will continue retreating for decades, even if greenhouse gas emissions stabilize, reducing the river's natural water storage capacity precisely when climate change intensifies water scarcity. The 40% reduction in water balance projected by 2070 would have profound implications for Santiago's seven million residents and the agricultural communities of the Maipo Valley.

An effective response requires protecting and restoring watershed ecosystems, improving agricultural water-use efficiency, reducing urban water consumption, coordinating water management across jurisdictions, and adapting to reduced availability through careful allocation among competing uses.

For Santiago's residents, the Maipo provides the most basic necessity of life—clean drinking water. Protecting this supply requires treating the entire watershed as critical infrastructure and accepting that climate change demands fundamental changes in how water is valued, managed, and used. Whether the Maipo can continue sustaining life in central Chile through the 21st century depends on actions taken today to protect its glacial sources, restore its watersheds, and use its waters wisely.

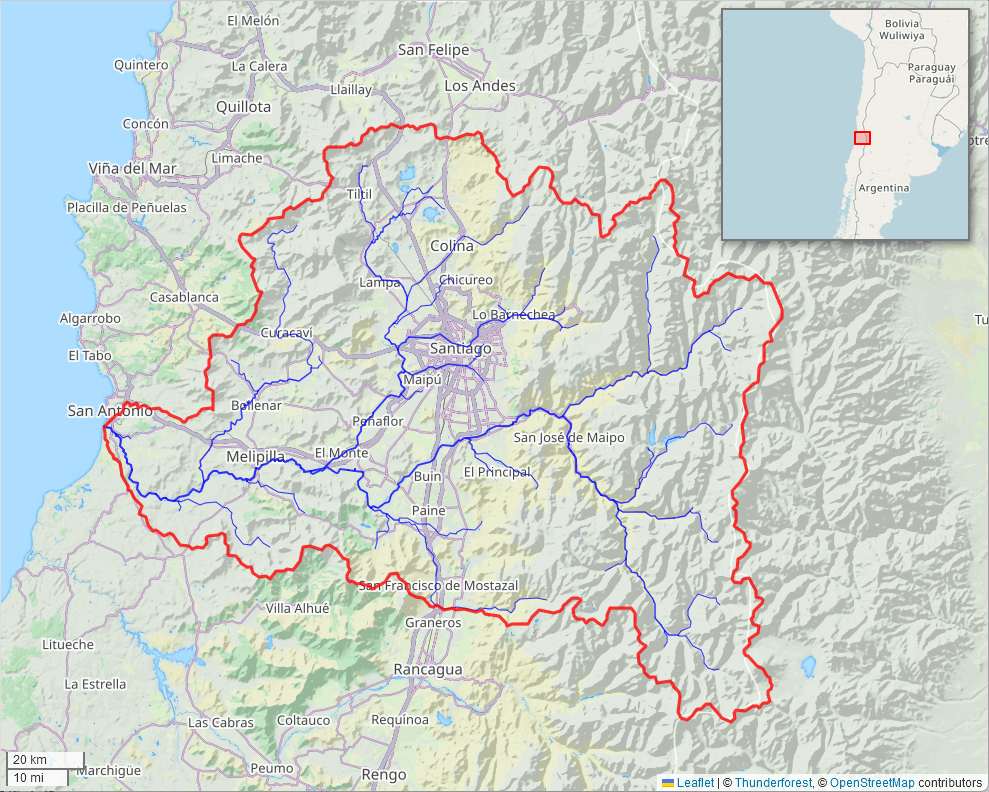

Map of the Maipo River watershed.