The Petén Basin and Maya Forest: Where Ancient Civilizations Meet Living Wilderness

In the heart of Central America, where Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize meet, lies a remarkable blend of natural wonder and human achievement. The Petén Basin and Maya Forest are more than geography—they show the ongoing interplay between civilization and wilderness over millennia.

Beneath the Emerald Canopy: Secrets of the Maya Forest and Petén Basin

In the verdant heart of Central America, where the borders of Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize converge in a tapestry of emerald green, lies one of the world's most extraordinary convergences of natural wonder and human achievement. The Petén Basin and its encompassing Maya Forest represent far more than geographical features—they embody a living testament to the intricate dance between civilization and wilderness that has unfolded across millennia.

Here, beneath canopies that have witnessed the rise and fall of empires, ancient limestone pyramids pierce through morning mists while jaguars pad silently along pathways once traversed by Maya kings. This is a landscape where the boundaries between archaeology and ecology, between past and present, dissolve into something altogether more profound—a place where the very stones seem to pulse with life, and where every stream whispers stories of both natural evolution and human ingenuity.

The Petén Basin: Cradle of Maya Civilization

Rising from the Caribbean lowlands like a vast natural amphitheater, the Petén Basin encompasses 35,854 square kilometers (13,843 square miles) of northern Guatemala's most remarkable terrain. This expansive limestone platform, sculpted by millions of years of geological patience, served as the stage upon which one of humanity's most sophisticated civilizations would reach its zenith.

The basin's topography reads like a geological symphony written in stone and water. Low limestone plateaus stretch endlessly beneath forest canopies, their surfaces punctuated by subtle undulations that reveal ancient beach ridges from long-vanished seas. Here and there, modest hills rise like green islands from the forest floor, their slopes cloaked in vegetation so dense that they seem to breathe with their own verdant life.

During the Late Preclassic and Classic periods, roughly from 400 BCE to 900 CE, this seemingly pristine wilderness supported one of the world's most densely populated regions. Archaeological evidence suggests that at its height around 750 CE, the Petén Basin was home to several million people, with some areas supporting approximately 2,000 individuals per square kilometer—a population density that rivals modern cities. The achievement becomes even more remarkable when one considers that this civilization flourished entirely within what we would today recognize as a tropical rainforest environment.

The great cities that arose from this landscape—Tikal, Calakmul, El Mirador, Yaxhá, and dozens of others—were not imposed upon the forest but rather grew from it, their architects and engineers working in harmony with the natural contours of the land. These urban centers developed what scholars now recognize as the distinctive "Petén style" of Maya architecture, characterized by towering pyramid-temples that seem to emerge organically from the forest canopy, their limestone facades carved with hieroglyphic texts that record the deeds of kings whose names still echo through the archaeological record.

Underground Cathedrals: The Hidden Hydrology of Petén

One of the Petén Basin's most remarkable features lies not on its surface, but deep beneath the forest floor. The region's limestone foundation has been slowly dissolving for millions of years, creating a vast underground universe of caves, rivers, and caverns that rivals any subway system ever conceived by human engineers. This karst landscape, invisible from above yet fundamental to all life in the region, represents one of the most extensive and complex hydrological systems in the Americas.

Unlike regions blessed with abundant surface water, the Petén Basin receives its generous tropical rainfall—often exceeding 2,000 millimeters (78 inches) annually—only to watch it vanish almost immediately into the porous limestone bedrock. Yet this apparent disappearance masks a far more intricate reality. The rainwater doesn't simply vanish; it embarks on underground journeys that may last decades or even centuries, flowing through limestone galleries that stretch for hundreds of kilometers beneath the forest floor.

These subterranean rivers emerge periodically as cenotes—natural sinkholes filled with crystal-clear water that the ancient Maya considered sacred portals to the underworld. The word "cenote" itself derives from the Maya term "dzonot," meaning sacred well, and these natural phenomena served not merely as water sources but as focal points for some of the most important religious ceremonies in Maya culture. Archaeological evidence from cenotes throughout the region reveals offerings of jade, gold, ceramics, and even human sacrifices, testament to the profound spiritual significance these waters held for ancient civilizations.

The cave systems themselves served multiple functions in Maya society. Beyond their hydrological importance, these underground chambers became sacred spaces where priests conducted ceremonies honoring the rain gods and Earth deities. The Maya cosmology envisioned the underworld as a watery realm ruled by powerful supernatural beings, and the caves provided literal access to this mythological landscape. Modern archaeological explorations continue to reveal ceramic vessels, stone altars, and hieroglyphic inscriptions deep within these caverns, evidence of ritual activities that continued for centuries.

Today, this underground hydrological system remains as vital as ever. The extensive aquifer beneath the Petén Basin provides freshwater not only for the region's wildlife but also for the communities that call this landscape home. The delicate balance between surface and subsurface water creates unique ecological conditions that support species assemblages found nowhere else on Earth.

Lake Petén Itzá, the basin's most prominent surface water feature, serves as a jewel within this hydrological crown. This ancient lake, measuring approximately 32 kilometers (20 miles) in length and 5 kilometers (3 miles) at its widest point, represents a rare instance where the underground water system emerges permanently at the surface. Surrounded by steep limestone cliffs and dense tropical vegetation, the lake creates its own microclimate that supports both endemic species and significant archaeological sites, including the historic town of Flores, built on a small island near the lake's center.

The Maya Forest: Mesoamerica's Emerald Heart

Extending far beyond the boundaries of the Petén Basin itself, the Maya Forest (Selva Maya) represents the largest continuous tropical rainforest in Mesoamerica, second only to the Amazon among New World forests. This magnificent ecosystem stretches across approximately 14 million hectares (34.6 million acres), encompassing portions of Mexico's Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Chiapas states, all of Belize, and northern Guatemala, including the entire Petén region.

The forest's scale alone inspires awe, but its true significance lies in the extraordinary complexity of its ecological relationships. This is not merely a collection of trees but rather a living superorganism where every element—from the towering emergent Ceiba pentandra (ceiba trees) that can reach heights of 60 meters (197 feet) to the microscopic fungi that decompose fallen leaves—plays a crucial role in maintaining the whole.

The Maya Forest's vertical architecture creates multiple worlds stacked one on top of another. In the emergent layer, massive hardwood species like Swietenia macrophylla (mahogany) and Cedrela odorata (Spanish cedar) create a canopy so dense that it can be walked upon, forming an aerial highway system used by countless arboreal species. Beneath this primary canopy, a secondary layer of smaller trees creates a complex three-dimensional matrix of branches, vines, and epiphytes that multiplies the available habitat exponentially.

Descending toward the forest floor, the understory becomes a twilight world where specialized plants have evolved to capture and utilize the mere 2-5% of sunlight that penetrates the multiple canopy layers above. Here, broad-leafed herbaceous plants create living carpets of green, while strangler figs begin their decades-long journey toward the canopy, eventually becoming some of the forest's most impressive giants.

The forest floor itself pulses with decomposition and renewal, as armies of insects, fungi, and bacteria break down the constant rain of organic matter from above, recycling nutrients with an efficiency that makes human industrial processes seem crude by comparison. This rapid nutrient cycling allows the forest to maintain its extraordinary productivity despite growing on soils that are often quite poor in conventional agricultural terms.

A Symphony of Biodiversity

Within this complex architectural framework, the Maya Forest supports one of the most diverse biological communities on Earth. The region harbors over 2,800 species of vascular plants, creating botanical diversity that rivals much larger Amazonian forests. Among these, numerous species remain scientifically undescribed, suggesting that the forest's biological wealth may be even greater than currently recognized.

The forest's mammalian fauna reads like a roll call of Neotropical icons. The Panthera onca (jaguar), the largest cat in the Americas, moves through these forests as both apex predator and ecosystem engineer. Recent research has revealed that jaguars in the Maya Forest represent genetically distinct populations that serve as crucial links between Central and South American jaguar populations, making their conservation critical for the species' long-term survival throughout its range.

Sharing the forest with these spotted cats, the smaller but equally impressive Puma concolor (puma) occupies similar habitats while avoiding direct competition through subtle differences in prey preferences and activity patterns. Both species serve as umbrella species—their conservation automatically protects vast areas of habitat that benefit countless other organisms.

The forest canopy comes alive with the brilliant flash of Ara macao (scarlet macaws), whose populations in the Maya Forest represent some of the last viable breeding communities of the endangered northern subspecies A. m. cyanoptera. These magnificent birds, with their striking red, yellow, and blue plumage, require large territories and specific nesting sites in old-growth trees, making them excellent indicators of forest health. Their loud calls, audible for kilometers through the forest, serve as a natural soundtrack to the wilderness experience.

Among the forest's most charismatic residents, troops of Alouatta pigra (Guatemalan black howler monkeys) contribute to one of nature's most impressive acoustic displays. Their territorial calls, amplified by specialized throat structures, can be heard up to 5 kilometers (3 miles) away, creating a dawn and dusk chorus that has echoed through these forests for millions of years. These primates serve crucial ecological roles as seed dispersers; their feeding habits help maintain the genetic diversity and spatial distribution of forest plants.

On the forest floor, herds of Tayassu pecari (white-lipped peccaries) crash through the undergrowth in groups that can number in the hundreds. These social mammals serve as the forest's primary soil engineers, their rooting behavior creating microhabitats that benefit countless other species while helping to cycle nutrients through the ecosystem.

The forest's vertical diversity extends to its smallest inhabitants as well. The canopy alone supports an estimated 40,000 insect species, many of them specialized for life in this three-dimensional aerial environment. Brilliant blue Morpho butterflies drift through sun-dappled clearings like living jewels, while armies of leafcutter ants (Atta spp.) maintain underground fungus gardens that represent some of the most sophisticated agricultural systems in the natural world.

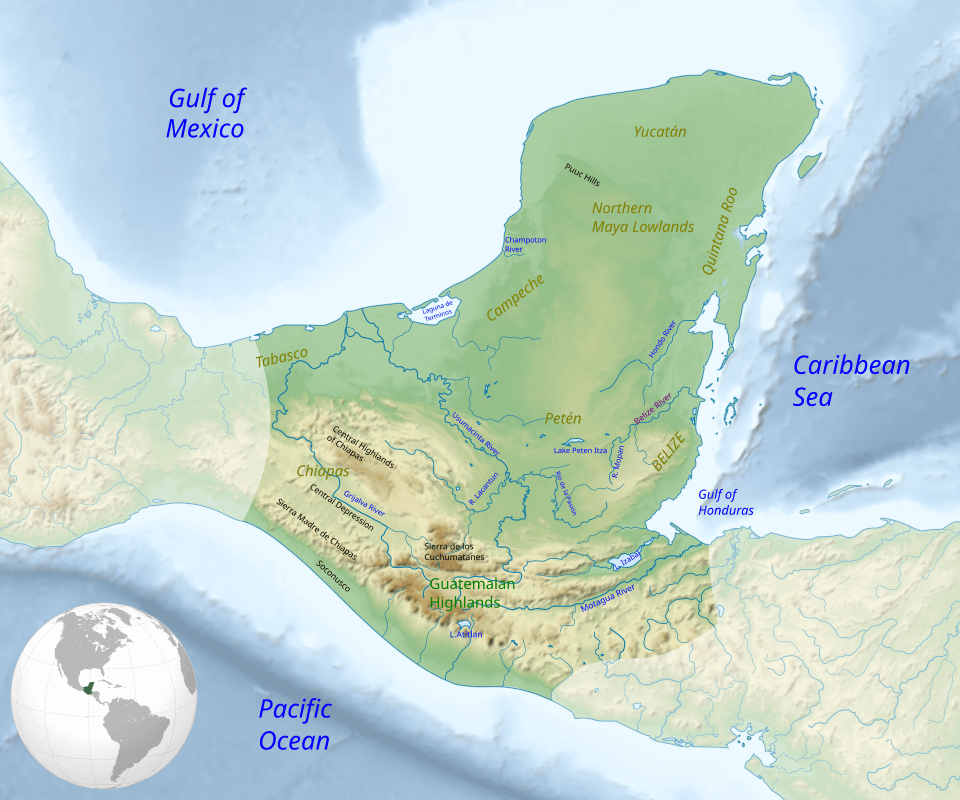

Map of the Maya region, with major rivers, mountain ranges, and regions.

Archaeological Landscapes: Cities in the Forest

What makes the Maya Forest truly unique among the world's great wilderness areas is the way it has integrated human history into its ecological fabric. Unlike regions where archaeological sites stand as monuments to vanished civilizations, the Maya Forest contains ruins that remain dynamically connected to their natural environment. Temples and palaces don't dominate the landscape but rather emerge from it, their limestone blocks slowly being reclaimed by strangler figs and tropical vines in a process that blurs the boundaries between natural and cultural heritage.

Tikal National Park, encompassing 575 square kilometers (222 square miles) of pristine rainforest, exemplifies this integration. Here, visitors can climb ancient pyramids that rise to 65 meters (213 feet) above the forest floor, their summits providing breathtaking views across an unbroken canopy that stretches to the horizon. Yet the archaeological importance of these structures cannot be separated from their ecological significance—the pyramids serve as artificial emergent trees, creating unique microclimates and providing nesting sites for raptors and other canopy species.

The Yaxhá-Nakum-Naranjo Cultural Triangle represents another remarkable example of this archaeological-ecological integration. This protected area encompasses not only three major Maya cities but also the watersheds, forest corridors, and habitat connections that allow wildlife populations to move freely across the landscape. The result is a management approach that recognizes cultural and natural heritage as inseparable elements of a single, integrated system.

Calakmul, designated as both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, takes this integration even further. The archaeological zone protects not only one of the Maya world's largest cities but also 723,185 hectares (1.8 million acres) of the most pristine tropical rainforest remaining in Mexico. Here, researchers studying ancient Maya agricultural systems work alongside biologists investigating jaguar ecology, their findings mutually reinforcing our understanding of how human societies can coexist sustainably with complex natural systems.

The Three Jewels: Biosphere Reserves as Conservation Anchors

The Maya Forest's conservation depends critically on three major protected areas that together form the backbone of regional ecosystem protection. Each represents a different national approach to balancing conservation with sustainable development, yet all three recognize the fundamental principle that effective conservation must integrate ecological, cultural, and social dimensions.

Guatemala's Maya Biosphere Reserve, established in 1990, covers 2.1 million hectares (5.2 million acres)—nearly one-fifth of the country's total territory. This massive protected area employs an innovative zoning system that includes strictly protected core areas, sustainably managed buffer zones, and multiple-use areas where local communities can engage in forest-friendly economic activities. The reserve protects not only biodiversity but also the traditional knowledge and practices of contemporary Maya communities whose ancestors built the great cities that dot the landscape.

Mexico's Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, encompassing 723,185 hectares (1.8 million acres), represents one of Mexico's most important tropical forest conservation successes. The reserve protects the headwaters of numerous river systems while serving as a crucial habitat corridor that connects forest fragments across the Yucatán Peninsula. Recent expansion of the protected area has strengthened these connections, creating opportunities for large mammals, such as jaguars, to maintain genetic exchange across their range.

The Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas adds another 331,200 hectares (818,394 acres) to this conservation network, protecting the upper watersheds of rivers that flow ultimately into both the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. This reserve encompasses some of Mexico's most pristine cloud forests, creating elevational gradients that support species assemblages found nowhere else in the Maya Forest system.

Together, these three biosphere reserves create a transnational conservation network that protects over 3.2 million hectares (7.9 million acres) of critical habitat while providing sustainable livelihood opportunities for Indigenous and local communities. Their success demonstrates that effective large-scale conservation requires cooperation across political boundaries and integration of multiple land uses within carefully designed management systems.

Contemporary Challenges and Community Solutions

Despite its protected status and international recognition, the Maya Forest faces unprecedented contemporary challenges that threaten its long-term survival. The forest stands at the intersection of multiple pressures: expanding agricultural frontiers, increasing demand for tropical hardwoods, growing tourism pressure, and climate change impacts that are altering precipitation patterns and increasing the frequency of severe storms.

Deforestation remains the single greatest threat to the forest's integrity. Satellite monitoring reveals that the Maya Forest has lost approximately 25% of its original extent over the past several decades, with clearing rates that fluctuate in response to economic incentives, enforcement capacity, and political stability. The loss is particularly severe along the forest's edges, where conversion to cattle ranching and large-scale agriculture creates a pattern of fragmentation that can disrupt ecological processes even in areas that remain forested.

Yet within this challenging context, innovative community-based conservation initiatives are demonstrating that alternatives to destructive land uses can provide both conservation benefits and economic opportunities for local people. Forest concessions in Guatemala's Maya Biosphere Reserve, for example, allow local communities to harvest timber, chicle latex, and non-timber forest products under strict sustainability guidelines. These operations generate significant income while maintaining forest cover and supporting wildlife populations.

Similarly, community-managed tourism initiatives are creating economic incentives for forest conservation while providing visitors with authentic cultural experiences. Maya communities that once relied primarily on subsistence agriculture are now developing expertise in hospitality, guiding, and artisan production, creating diversified local economies that depend on maintaining healthy forest ecosystems.

The harvesting of chicle—the latex of the Manilkara zapota (sapodilla) tree—represents another traditional practice that has found new relevance in contemporary conservation strategies. Chicle harvesters, known as chicleros, maintain intimate knowledge of forest ecology while providing a sustainable source of natural latex for specialty products. Their work requires maintaining large areas of intact forest, creating direct economic incentives for conservation.

Climate Change and Forest Resilience

Recent research has revealed that the Maya Forest plays a crucial role in regional climate regulation, generating approximately 75% of its own rainfall through evapotranspiration from its vast leaf surfaces. This self-sustaining hydrological cycle makes the forest remarkably resilient to moderate climate variations, but also means that large-scale deforestation could trigger irreversible changes in regional precipitation patterns.

Climate change projections for the region suggest increasing temperatures, more variable precipitation, and stronger tropical storms—all of which could stress forest ecosystems in unprecedented ways. However, the forest's extraordinary diversity may also represent its greatest asset in adapting to changing conditions. The presence of multiple species occupying similar ecological roles provides redundancy that can maintain ecosystem functions even if individual species face local extinctions.

Conservation scientists are increasingly recognizing that protecting the Maya Forest requires thinking beyond traditional park boundaries to consider the broader landscape matrix in which protected areas are embedded. This has led to innovative approaches, such as payment for ecosystem services programs that compensate landowners for maintaining forest cover, and sustainable certification systems that enable consumers to support forest-friendly products from the region.

Looking Forward: A Vision for Coexistence

The Maya Forest and Petén Basin represent far more than a collection of protected areas or archaeological sites—they embody a vision of human-nature coexistence that becomes increasingly relevant as our planet faces the challenges of the twenty-first century. Here, in landscapes where ancient cities remain integrated with living forests, where traditional knowledge combines with modern science, and where conservation success depends on the prosperity of local communities, we find models for sustainability that transcend simple preservation.

The challenge now lies in scaling these successful local initiatives to match the magnitude of contemporary threats. This will require continued international cooperation, innovative financing mechanisms, and recognition that the benefits provided by healthy forest ecosystems—from carbon storage to biodiversity conservation to cultural preservation—represent global public goods worthy of international investment.

Perhaps most importantly, the Maya Forest reminds us that the boundaries between nature and culture, between conservation and development, between past and future, are far more permeable than we often imagine. In landscapes where jaguars den in ancient temples and where Indigenous communities maintain both traditional practices and modern conservation expertise, we glimpse possibilities for a world where human societies enhance rather than degrade the natural systems that sustain all life.

As dawn breaks over the forest canopy and the calls of howler monkeys echo from pyramid summits, the Maya Forest continues its ancient work of weaving together all the threads of life into patterns of extraordinary beauty and resilience. In protecting this remarkable landscape, we protect not only an irreplaceable natural heritage but also a living testament to humanity's capacity for coexistence with the more-than-human world.