The Geography of Nicaragua: Land of Lakes and Volcanoes

Nicaragua is the largest country in Central America, acting as a key link between North and South America due to its central location. Its landscape includes volcanic peaks in the Cordillera Los Maribios and wetlands along the Mosquito Coast, reflecting geological, climatic, and ecological history.

The Natural Heritage of Nicaragua: From Caribbean Lowlands to Pacific Peaks

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, stands as Central America's largest country by land area, covering approximately 130,375 square kilometers (50,337 square miles). Located at the geographic heart of the Central American isthmus, Nicaragua serves as a crucial bridge between North and South America, bordered by Honduras to the north, Costa Rica to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. This strategic position has profoundly shaped the nation's physical geography, climate patterns, biodiversity, and human settlement patterns throughout its history.

The country's distinctive geography is characterized by three primary physiographic regions: the Pacific Lowlands, the Central Highlands, and the Caribbean Lowlands. Each region possesses unique topographical features, climatic conditions, and ecological characteristics that contribute to Nicaragua's remarkable environmental diversity. From the volcanic peaks of the Cordillera Los Maribios to the extensive wetlands of the Mosquito Coast, Nicaragua's landscape tells a complex story of geological evolution, climatic variation, and ecological adaptation.

Physical Geography and Topography

The Pacific Lowlands

The Pacific Lowlands, known locally as the Región del Pacífico, encompass the western portion of Nicaragua, extending from the Pacific coast inland to the base of the central mountain ranges. This region covers approximately 15% of the country's total land area and represents the most densely populated and economically developed zone of Nicaragua. The lowlands are characterized by relatively flat terrain, with elevations rarely exceeding 200 meters (656 feet) above sea level.

The Pacific Lowlands are dominated by a chain of volcanic peaks running parallel to the Pacific coast, known as the Cordillera Los Maribios. This volcanic chain includes some of Nicaragua's most prominent geological features, including Volcán Momotombo (1,297 meters or 4,255 feet), Volcán Masaya (635 meters or 2,083 feet), and Volcán Concepción (1,610 meters or 5,282 feet) on Ometepe Island. These volcanoes have played a crucial role in shaping the region's topography through millennia of volcanic activity, creating fertile soils that have supported intensive agriculture and dense human settlement.

The coastal plain itself varies in width from 15 to 75 kilometers (9 to 47 miles), featuring a relatively straight coastline punctuated by several significant bays and estuaries. The Gulf of Fonseca in the northwest and the Brito River delta in the southwest represent the most notable coastal indentations. The region's drainage is dominated by short rivers flowing westward to the Pacific, including the Río Tamarindo and Río Brito.

The Central Highlands

The Central Highlands, or Región Central, form the mountainous backbone of Nicaragua, extending diagonally across the country from northwest to southeast. This region covers approximately 25% of Nicaragua's territory and includes the country's highest elevations. The highlands are part of the larger Central American Cordillera system, representing the continuation of the Sierra Madre mountain chain from Mexico.

The highest point in Nicaragua is Pico Mogotón, which reaches 2,107 meters (6,913 feet) above sea level in the Cordillera Entre Ríos, located along the Honduran border. The Central Highlands are characterized by complex topography, featuring steep-sided valleys, elevated plateaus, and numerous peaks that exceed 1,500 meters (4,921 feet) in elevation. The region's rugged terrain has historically served as a natural barrier between the Pacific and Caribbean watersheds, influencing patterns of human settlement and economic development.

The highlands are drained by several major river systems, including the upper reaches of the Río Coco (also known as the Río Segovia), Nicaragua's longest river, which is approximately 680 kilometers (422 miles) long. The mountainous terrain creates numerous microclimates, supporting diverse forest ecosystems that range from cloud forests at higher elevations to pine-oak forests on intermediate slopes.

The Caribbean Lowlands

The Caribbean Lowlands, or Costa Atlántica, comprise the eastern half of Nicaragua, covering approximately 60% of the country's total land area. This vast region extends from the base of the Central Highlands eastward to the Caribbean Sea, characterized by low-lying terrain, extensive wetlands, and dense tropical forests. Elevations throughout most of the region remain below 100 meters (328 feet) above sea level, creating ideal conditions for the development of expansive river systems and coastal lagoons.

The Caribbean Lowlands are characterized by their intricate hydrological systems, which feature numerous rivers, wetlands, and coastal lagoons. The region's largest rivers include the Río Coco along the northern border with Honduras, the Río Grande de Matagalpa, and the Río San Juan along the southern border with Costa Rica. These rivers meander through the lowlands, creating extensive floodplains and deltaic deposits that support rich agricultural soils and diverse aquatic ecosystems.

The Caribbean coastline extends for approximately 540 kilometers (335 miles) and is characterized by barrier islands, coastal lagoons, mangrove forests, and sandy beaches. The Mosquito Coast, as this region is historically known, features several significant lagoons, including Laguna de Perlas and Laguna de Bluefields, which serve as important fishing grounds and transportation corridors for local communities.

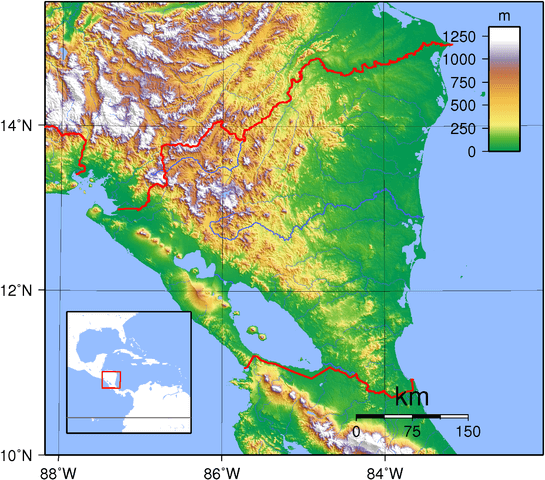

Topographic map of Nicaragua.

Major Water Bodies

Lakes and Inland Waters

Nicaragua is renowned for its impressive inland water bodies, most notably Lake Nicaragua (Lago de Nicaragua or Lago Cocibolca) and Lake Managua (Lago de Managua or Lago Xolotlán). These lakes represent some of Central America's most significant freshwater resources, playing a crucial role in the country's geography, ecology, and economy.

Lake Nicaragua, spanning approximately 8,264 square kilometers (3,191 square miles), is the largest lake in Central America and the second-largest in Latin America, after Lake Titicaca. The lake reaches maximum depths of approximately 60 meters (197 feet) and contains several islands, including the famous Ometepe Island, formed by two volcanic peaks rising directly from the lake's waters. Lake Nicaragua is notable for its unique ecosystem, which supports several endemic species, including the Nicaragua shark (Carcharhinus nicaraguensis). However, recent research suggests that these may be bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) that have adapted to freshwater conditions.

Lake Managua covers approximately 1,042 square kilometers (402 square miles) and reaches maximum depths of about 30 meters (98 feet). Located northwest of Lake Nicaragua, this lake has faced significant environmental challenges due to industrial pollution and urban runoff from Managua, the capital city located on its southern shore. Despite these challenges, the lake remains an important ecological and economic resource.

The two large lakes are connected by the Río Tipitapa, a short river that flows intermittently depending on seasonal water levels. This hydrological connection creates a unified lake system that ultimately drains to the Caribbean Sea via the Río San Juan.

River Systems

Nicaragua's river systems are divided between two major watersheds: the Pacific and Caribbean basins. The Pacific watershed covers approximately 13% of the country's territory and features relatively short rivers due to the proximity of the volcanic highlands to the Pacific coast. These rivers typically flow westward and are characterized by steep gradients and seasonal fluctuations in their flow.

The Caribbean watershed encompasses the remaining 87% of Nicaragua's territory and includes the country's major river systems. The Río Coco, flowing along Nicaragua's northern border with Honduras, is the country's longest river and serves as an important transportation corridor for remote communities in the northeastern regions. The river's total length within Nicaragua is approximately 680 kilometers (422 miles), and it drains a vast watershed covering much of the northern highlands and lowlands.

The Río San Juan, flowing eastward from Lake Nicaragua to the Caribbean Sea, holds particular historical and geographical significance. This 200-kilometer (124-mile) river has long been considered a potential route for an interoceanic canal and serves as the border with Costa Rica along its lower reaches. The river's strategic importance has made it a focal point of regional geopolitics and conservation efforts.

Climate and Weather Patterns

Nicaragua's climate is predominantly tropical, characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons influenced by the country's location between two major bodies of water and its varied topography. The climate exhibits significant regional variations due to differences in elevation, distance from the ocean, and exposure to prevailing winds.

Regional Climate Variations

The Pacific Lowlands experience a tropical savanna climate, characterized by pronounced seasonality. The dry season typically extends from November to April, characterized by clear skies, minimal precipitation, and temperatures ranging from 27°C to 35°C (81°F to 95°F). The wet season spans from May to October, bringing substantial rainfall that can exceed 2,000 millimeters (79 inches) annually in some areas. During this period, afternoon thunderstorms are common, and tropical cyclones occasionally affect the region.

The Central Highlands exhibit a more temperate climate due to their elevation, with temperatures generally decreasing by approximately 6°C per 1,000 meters (3.3°F per 1,000 feet) of elevation. Higher elevations experience cooler temperatures year-round, with average temperatures ranging from 18°C to 25°C (64°F to 77°F) in areas above 1,000 meters (3,281 feet). The highlands receive substantial precipitation, particularly on windward slopes exposed to moisture-laden trade winds.

The Caribbean Lowlands experience a tropical rainforest climate with high humidity and abundant precipitation throughout the year. This region receives significantly more rainfall than the Pacific side, with annual totals often exceeding 3,000 millimeters (118 inches) in some areas. The wettest months typically occur from September to January, coinciding with the passage of tropical weather systems and the positioning of the Intertropical Convergence Zone.

Seasonal Patterns and Extreme Weather

Nicaragua's weather patterns are strongly influenced by the migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, trade wind patterns, and sea surface temperatures in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. The country is vulnerable to various extreme weather events, including hurricanes, tropical storms, droughts, and flooding.

Hurricane activity represents one of the most significant climatic threats to Nicaragua, particularly along the Caribbean coast. The hurricane season extends from June to November, with peak activity typically occurring between August and October. Notable hurricanes that have impacted Nicaragua include Hurricane Mitch in 1998, which caused catastrophic flooding and landslides, and more recently, Hurricanes Eta and Iota in 2020, which struck within two weeks of each other.

El Niño and La Niña phenomena significantly influence Nicaragua's climate patterns, particularly affecting precipitation distribution and intensity. El Niño events typically bring reduced rainfall to the Pacific regions and can exacerbate drought conditions, while La Niña events often increase hurricane activity and precipitation along the Caribbean coast.

Biodiversity and Ecosystems

Nicaragua's diverse geography supports a remarkable biodiversity, with the country serving as a crucial biological corridor between the North American and South American ecosystems. The nation's varied elevations, climate zones, and habitats support an estimated 17,000 species of flora and fauna, making it one of the most biodiverse countries in Central America relative to its size.

Forest Ecosystems

Tropical rainforests dominate the Caribbean Lowlands, characterized by high species diversity, complex vertical stratification, and dense canopy cover. These forests support numerous endemic species and serve as habitats for iconic species such as the jaguar (Panthera onca), the three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus), and the scarlet macaw (Ara macao). The region's forests also include significant areas of pine savanna, particularly in areas with sandy soils and seasonal flooding.

The Central Highlands support several distinct forest types, including cloud forests at higher elevations, characterized by persistent cloud cover and high humidity. These ecosystems harbor numerous endemic plant species and serve as crucial watersheds for the country's river systems. Pine-oak forests occur at intermediate elevations, supporting species such as the Nicaraguan pine (Pinus oocarpa) and various oak species (Quercus spp.).

Dry tropical forests characterize much of the Pacific Lowlands, adapted to pronounced seasonality and extended dry periods. These forests support species adapted to water stress, including numerous cacti, thorny shrubs, and deciduous trees that shed their leaves during the dry season. Many of these ecosystems have been converted to agricultural land, making the remaining fragments particularly valuable for conservation.

Aquatic Ecosystems

Nicaragua's extensive aquatic ecosystems support diverse assemblages of freshwater and marine species. Lake Nicaragua's unique ecosystem includes several endemic cichlid fish species and supports populations of bull sharks that have adapted to freshwater conditions. The lake's islands, particularly Ometepe, support distinct ecological communities influenced by volcanic soils and isolated evolution.

Coastal mangrove ecosystems along both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts provide crucial habitat for numerous species and serve important ecological functions, including coastal protection and nursery areas for marine species. The Caribbean coast's extensive mangrove systems support species such as the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) and American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus).

Coral reef ecosystems along the Caribbean coast, including the Corn Islands, support diverse marine communities and contribute to local fisheries and tourism. These ecosystems face increasing pressure from climate change, pollution, and overfishing, highlighting the need for comprehensive conservation strategies.

Endemic and Threatened Species

Nicaragua supports numerous endemic species, particularly in isolated habitats such as volcanic islands and highland forests. The Nicaragua grackle (Quiscalus nicaraguensis) is endemic to Lake Nicaragua and its islands, while several cichlid fish species are found nowhere else in the world. The country also serves as habitat for numerous migratory species, including millions of birds that utilize Central America as a flyway between North and South American breeding and wintering grounds.

Many of Nicaragua's species face conservation challenges due to habitat loss, hunting pressure, and climate change. The jaguar, the national bird, the yellow-naped parrot (Amazona auropalliata), and the Central American tapir (Tapirus bairdii) are among the species requiring conservation attention. The country's position as a biological corridor makes it particularly important for maintaining connectivity between protected areas throughout Central America.

Geological Features and Natural Hazards

Nicaragua's location along the Pacific Ring of Fire and at the boundary between the Caribbean Plate and the Cocos Plate creates a geologically dynamic landscape characterized by active volcanism, seismic activity, and diverse mineral resources. Understanding these geological processes is crucial for appreciating both the opportunities and challenges that Nicaragua's physical geography presents.

Volcanic Activity

Nicaragua hosts 19 active volcanoes, making it one of the most volcanically active countries in Central America. These volcanoes are primarily distributed along two main chains: the Cordillera Los Maribios in the Pacific Lowlands and the Cordillera Isabelia in the north-central region. Volcanic activity has profoundly shaped Nicaragua's landscape, creating fertile soils, geothermal energy resources, and distinctive topographical features.

Volcán Masaya, located just southeast of Managua, represents one of Nicaragua's most active and accessible volcanoes. The volcano features a persistent lava lake and has erupted numerous times throughout recorded history. Volcán Momotombo, rising dramatically from the shores of Lake Managua, has been inactive for several decades but remains closely monitored due to its proximity to populated areas.

The twin volcanoes of Ometepe Island, Volcán Concepción and Volcán Maderas, create one of Nicaragua's most iconic landscapes. These volcanoes rise directly from Lake Nicaragua, creating a unique island ecosystem that supports both agricultural communities and diverse natural habitats. Volcán Concepción remains active, with its last major eruption occurring in 2010.

Seismic Activity

Nicaragua experiences frequent seismic activity due to its position at the convergence of major tectonic plates. Three primary fault systems affect the country: the Middle America Trench along the Pacific coast, the Polochic-Motagua fault system in the north, and various local fault systems associated with volcanic activity.

The capital city of Managua has been particularly affected by seismic activity, suffering devastating earthquakes in 1931 and 1972 that caused extensive damage and loss of life. The 1972 earthquake, measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale, destroyed much of downtown Managua and led to significant changes in urban planning and building codes throughout the country.

Seismic monitoring systems throughout Nicaragua track earthquake activity and provide early warning capabilities for both volcanic and tectonic earthquakes. Understanding seismic patterns is crucial for infrastructure development, urban planning, and disaster preparedness nationwide.

Mineral Resources

Nicaragua's geological diversity has led to the discovery of significant mineral resources, including gold, silver, copper, zinc, and various industrial minerals. The country's mining history dates back to pre-Columbian times, with modern mining operations making a substantial contribution to the national economy.

Gold represents Nicaragua's most important mineral resource, with major deposits located in the north-central highlands. The Bonanza and Rosita mining districts have produced gold for over a century, while newer operations continue to explore and develop additional deposits. Silver, copper, and zinc deposits often occur in association with gold mineralization, creating polymetallic ore bodies that support diversified mining operations.

Geothermal energy represents a growing renewable resource sector, with Nicaragua's volcanic activity providing substantial potential for geothermal power generation. The Momotombo geothermal field, situated near the active volcano, has been generating electricity since the 1980s, while additional geothermal projects are currently under development throughout the volcanic region.

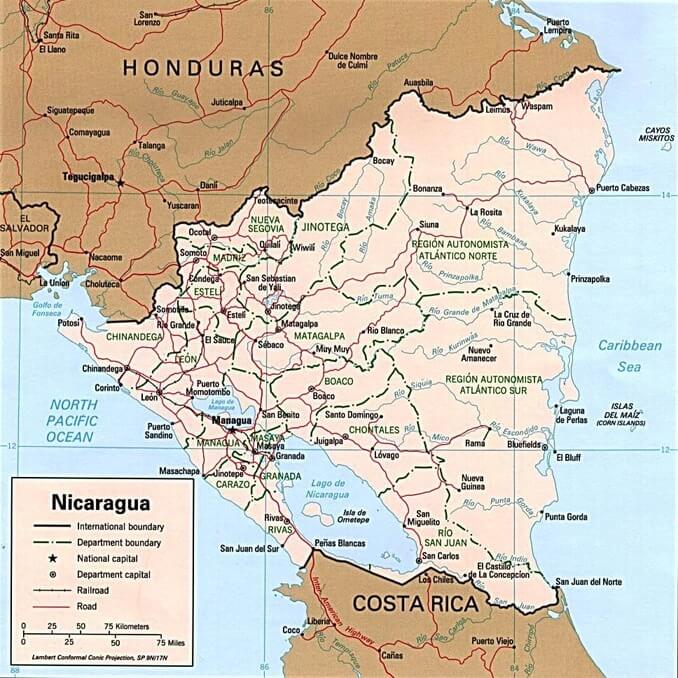

Political map of Nicaragua.

Human Geography and Settlement Patterns

Nicaragua's physical geography has profoundly influenced patterns of human settlement, economic development, and cultural evolution throughout the country's history. The distribution of population, infrastructure, and economic activities reflects the complex interplay between environmental opportunities and constraints presented by the country's diverse landscapes.

Population Distribution

Nicaragua's population of approximately 6.9 million people is distributed unevenly across the country's three major geographic regions, with the Pacific Lowlands supporting the highest population densities despite comprising only 15% of the national territory. This region comprises approximately 60% of the country's population, including the capital city of Managua, which has a metropolitan area of over 1.5 million inhabitants.

The Central Highlands support approximately 25% of Nicaragua's population, primarily in highland valleys and plateau areas that offer favorable climates and fertile soils for agriculture. Cities such as Matagalpa, Jinotega, and Estelí serve as regional centers for coffee production and other highland agricultural activities.

The Caribbean Lowlands, which cover 60% of Nicaragua's national territory, support only about 15% of the country's population. The region's challenging climate, limited transportation infrastructure, and relative isolation from national markets have historically limited population growth and economic development. However, the region maintains distinct cultural characteristics, with significant populations of Indigenous Miskito, Mayangna, and Afro-descendant communities.

Urban Development

Nicaragua's urban hierarchy reflects the geographic concentration of economic and political power in the Pacific region. Managua dominates the urban system as the primary city, concentrating government, financial services, manufacturing, and transportation functions. The city's location on the southern shore of Lake Managua provides access to freshwater resources while its position in the Pacific Lowlands facilitates connections to both domestic and international markets.

Secondary cities such as León, Granada, Masaya, and Chinandega are distributed throughout the Pacific Lowlands, each serving distinct regional functions. León, the colonial capital and current university center, benefits from its location in the fertile northwestern lowlands. Granada, situated on the shores of Lake Nicaragua, serves as a commercial and tourism center while maintaining its colonial architectural heritage.

The Caribbean coast's urban centers, including Bluefields and Puerto Cabezas (also known as Bilwi), remain relatively small but serve crucial functions as regional administrative and commercial hubs. These cities face unique challenges related to their isolation from national transportation networks and their vulnerability to hurricane impacts.

Transportation and Infrastructure

Nicaragua's transportation infrastructure reflects the challenges and opportunities presented by its physical geography. The Pan-American Highway serves as the country's primary transportation corridor, connecting major cities in the Pacific Lowlands and providing access to neighboring countries. This highway system follows the relatively flat terrain of the Pacific region, avoiding the rugged topography of the central highlands.

Transportation connections between the Pacific and Caribbean regions remain limited due to the challenging terrain of the central highlands and the extensive wetlands of the Caribbean lowlands. The few roads crossing the country require substantial engineering to navigate steep mountain passes and river crossings, making these connections expensive to build and maintain.

Water transportation plays a crucial role in the Caribbean region, where rivers and coastal waters provide access to communities that lack road connections. The Río San Juan and Río Coco serve as important transportation corridors, while coastal vessels connect Caribbean communities with regional centers and international markets.

Economic Geography

Nicaragua's economic geography reflects the diverse opportunities and constraints presented by its varied physical environments. The country's economy depends heavily on natural resource exploitation, agriculture, and manufacturing, with each sector showing distinct geographic patterns of development.

Agricultural Systems

Agriculture is a crucial component of Nicaragua's economy, employing approximately 25% of the country's workforce and contributing significantly to its export earnings. The geographic distribution of agricultural activities reflects variations in climate, soils, and topography across the country's different regions.

The Pacific Lowlands support intensive agricultural production, including sugarcane, cotton, and various food crops. The region's volcanic soils provide excellent fertility, while the pronounced dry season facilitates mechanized farming and crop harvesting. Large-scale plantations and processing facilities characterize much of this region's agricultural landscape.

Coffee production dominates agricultural activities in the Central Highlands, where cooler temperatures and abundant rainfall create ideal conditions for growing coffee. Nicaragua's coffee regions, including Matagalpa, Jinotega, and Nueva Segovia, produce high-quality arabica coffee that commands premium prices in international markets. The mountainous terrain necessitates labor-intensive cultivation methods, yet it supports sustainable farming practices that preserve forest cover and biodiversity.

Cattle ranching is prevalent throughout Nicaragua, but it is particularly significant in the Caribbean Lowlands, where extensive grasslands support large herds of cattle. The region's humid climate and abundant water resources provide year-round grazing opportunities, though infrastructure limitations restrict access to processing facilities and markets.

Natural Resource Industries

Nicaragua's natural resource industries, including mining, forestry, and fishing, show distinct geographic patterns related to resource distribution and accessibility. Mining activities concentrate in the north-central highlands, where geological conditions have created significant mineral deposits. The Bonanza Triangle, encompassing parts of the RAAN and RAAS autonomous regions, supports both large-scale and artisanal mining operations.

Forestry operations occur primarily in the Caribbean Lowlands, where extensive forest resources support both timber extraction and conservation activities. The region's remoteness and limited infrastructure create challenges for sustainable forest management, while international demand for tropical timber provides economic incentives for forest exploitation.

Fishing activities occur along both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, with each region supporting distinct fisheries. Pacific coast fishing focuses primarily on tuna, shrimp, and various inshore species, while Caribbean coast fisheries target lobster, conch, and various reef fish species. Shrimp aquaculture has become increasingly important along the Pacific coast, capitalizing on coastal lagoons and mangrove areas.

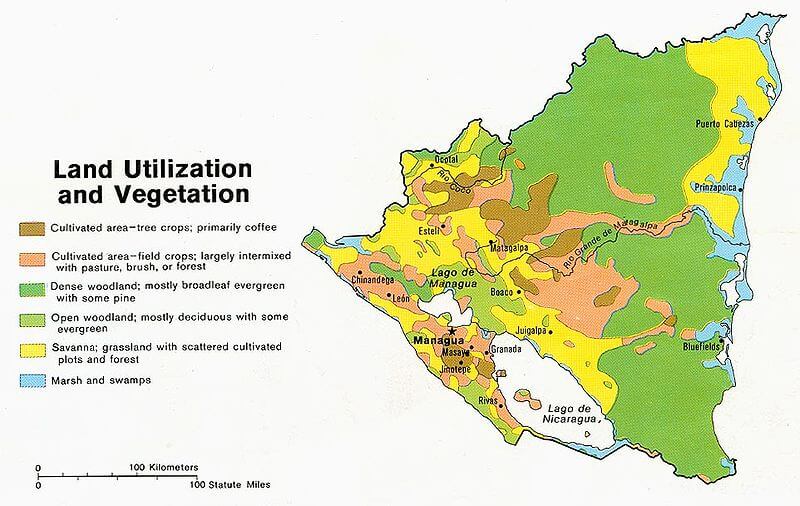

Nicaragua land use and vegetation map.

Environmental Challenges and Conservation

Nicaragua faces numerous environmental challenges related to its geographic characteristics, population pressures, and economic development needs. Understanding these challenges is crucial for developing sustainable management strategies that balance conservation goals with human development needs.

Deforestation and Land Use Change

Deforestation represents one of Nicaragua's most pressing environmental challenges, with forest cover declining from approximately 60% in 1950 to less than 25% today. The greatest forest losses have occurred in the Caribbean Lowlands, where agricultural expansion, cattle ranching, and timber extraction have resulted in the elimination of vast areas of primary forest.

The agricultural frontier continues to advance eastward from the Pacific and central regions, driven by population growth, land tenure issues, and economic pressures. Small-scale farmers often clear forest areas for subsistence agriculture, while larger operations establish cattle ranches and commercial farms. This pattern of land-use change threatens biodiversity, watershed functions, and the climate-regulation services provided by forest ecosystems.

Efforts to address deforestation include the establishment of protected areas, reforestation programs, and sustainable land management initiatives. However, the effectiveness of these measures is limited by insufficient funding, weak enforcement capabilities, and competing economic pressures.

Water Resource Management

Nicaragua's abundant water resources face increasing pressure from population growth, agricultural development, and industrial activities. Lake Managua has suffered severe pollution from untreated urban and industrial waste, creating public health concerns and ecological degradation. Despite cleanup efforts, the lake continues to receive contaminated runoff from Managua and the surrounding areas.

Water quality issues also affect rural areas, where agricultural chemicals, mining activities, and inadequate sanitation systems contaminate both surface and groundwater resources. The Caribbean region's extensive river systems face particular challenges from agricultural runoff and pollution from mining in upstream watersheds.

Climate change poses additional challenges for water resource management, with projections indicating increased variability in precipitation patterns and more frequent extreme weather events. These changes could impact both water availability and flood risks nationwide.

Coastal and Marine Conservation

Nicaragua's extensive coastline faces various environmental pressures, including coastal development, pollution, overfishing, and the impacts of climate change. Mangrove ecosystems, which provide crucial coastal protection and serve as habitats for fisheries, have been degraded by shrimp farming, urban development, and pollution.

Caribbean coral reefs face threats from rising sea temperatures, ocean acidification, pollution, and physical damage from hurricanes and human activities. These ecosystems support important fisheries and tourism activities, while also providing crucial coastal protection services.

Marine protected areas have been established along both coasts; however, enforcement remains challenging due to limited resources and the remote locations of many coastal areas. Sustainable fisheries management requires improved monitoring, regulation, and the development of alternative livelihoods for fishing communities.

Conclusion

Nicaragua's geography represents a remarkable convergence of geological, climatic, and biological processes that have created one of Central America's most diverse and dynamic landscapes. From the volcanic peaks of the Pacific Lowlands to the extensive wetlands along the Caribbean coast, the country's diverse environments support a rich biodiversity, diverse human communities, and important economic activities.

The geographic distribution of population, economic activities, and infrastructure reflects the complex interplay between environmental opportunities and constraints. The Pacific Lowlands' fertile soils, favorable climate, and accessibility have made this region the country's demographic and economic center, while the Central Highlands' coffee-growing potential has created a distinct regional economy based on high-value agricultural exports. The Caribbean Lowlands remain relatively undeveloped, yet they contain vast natural resources and maintain important cultural diversity.

Understanding Nicaragua's geography is essential for addressing the country's environmental challenges and development needs. Climate change, deforestation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss necessitate comprehensive responses that account for the intricate relationships between human activities and natural systems. Sustainable development strategies must balance conservation goals with legitimate human needs while recognizing the crucial role that healthy ecosystems play in supporting long-term prosperity.

Nicaragua's position as a biological and cultural bridge between North and South America places the country in a unique position to assume special responsibilities for maintaining ecological connectivity and protecting its shared natural heritage. The country's geographic diversity represents both a tremendous asset and a significant challenge, requiring careful stewardship to ensure that future generations can benefit from the remarkable landscapes and resources that define this unique Central American nation.

The ongoing evolution of Nicaragua's geography, driven by volcanic activity, climate variability, and human activities, ensures that this landscape will continue to change and adapt. Understanding these processes and their implications for human communities and natural systems remains crucial for anyone seeking to comprehend the complex relationships between people and place in this geographically dynamic country.