The Qhapaq Ñan: Weaving an Empire Through Stone and Sky

Stretching across the spine of South America, the Qhapaq Ñan represents one of humanity's most ambitious engineering achievements. More than mere roads, these ancient highways bound together a realm that spanned from the emerald depths of the Amazon to the windswept altiplano.

Binding the Four Worlds: The Engineering Legacy of the Andean Road Network

Stretching like silver threads across the spine of South America, the Qhapaq Ñan—meaning "Beautiful Road" in Quechua and often called the “Great Inca Road” in English—represents one of humanity's most ambitious engineering achievements. This magnificent network of pathways once carried the footsteps of Lama glama (llamas) laden with precious cargo, Vicugna pacos (alpacas) bearing the finest textiles, and chasqui messengers racing between distant provinces of the vast Inca Empire. More than mere roads, these ancient highways served as the nervous system of Tawantinsuyu, the "Land of the Four Quarters," binding together a realm that spanned from the emerald depths of the Amazon to the windswept altiplano.

The Scope of Imperial Ambition

The scale of the Qhapaq Ñan defies easy comprehension. Covering 30,000 kilometers (18,640 miles) of meticulously engineered pathways, this network dwarfs many modern highway systems. To put this achievement in perspective, travelers following the complete system would traverse a distance equivalent to three-quarters of Earth's circumference. The whole network connected various production, administrative, and ceremonial centres constructed over more than 2,000 years of pre-Inca Andean culture, representing not merely Inca construction but the culmination of millennia of Andean engineering wisdom.

The UNESCO World Heritage designation encompasses over 720 kilometers (447 miles) of road and 273 archaeological sites, though this represents only a fraction of the original network. The Qhapaq Ñan is built around four principal routes, all starting in the main square of Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire, radiating outward like the cardinal directions of the Inca cosmological understanding.

Engineering Marvels Across Impossible Terrain

The Inca engineers faced challenges that would intimidate modern construction teams. Their roads carved through the Andes at altitudes exceeding 4,000 meters (13,123 feet), descended into tropical valleys, and traversed the Atacama Desert—one of Earth's most arid regions. Where solid bedrock blocked their path, they carved steps directly into living stone. Where deep chasms interrupted their progress, they wove bridges from Stipa ichu (Andean grass) and other plant fibers, creating suspension spans that swayed safely above thundering rivers.

The engineering solutions varied dramatically with the terrain. Along coastal routes, workers laid flat stones to create stable surfaces across shifting sands. In mountainous regions, they constructed retaining walls and drainage systems that have remained functional for over five centuries. The famous sections near Machu Picchu showcase their mastery of integrating infrastructure with landscape—roads that seem to flow naturally with the mountain contours while maintaining precise gradients suitable for human porters and pack animals.

Perhaps most remarkably, the Incas achieved this without wheeled vehicles, draft animals larger than llamas, or iron tools. Every stone was quarried, shaped, and positioned using bronze implements, wooden levers, and human strength coordinated through sophisticated organizational systems.

The Four Sacred Directions

The Qhapaq Ñan's design reflected the Inca understanding of their empire as a sacred geography. The Inka called their empire Tawantinsuyu, which means "The Four Regions Together", and the road network served as both practical infrastructure and spiritual metaphor for imperial unity. Each of the four primary routes emanated from Cusco's central plaza—the Huacaypata—toward one of the cardinal directions, connecting the capital to distinct ecological and cultural zones.

The Chinchaysuyu route stretched northwest through present-day Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, traversing cloud forests and connecting with sophisticated cultures that had developed their own road systems centuries before the arrival of the Inca. Collasuyu covered southern Peru and parts of Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. Its extensive grassland was ideal for llama and alpaca herding, and the roads through this region facilitated the movement of camelid herds and precious metals. The Cuntisuyu route descended toward the Pacific coast, connecting highland administrative centers with fishing communities and coastal trade networks. Finally, the Antisuyu route plunged into the Amazon Basin, where Antisuyu had a tropical climate and provided access to exotic goods like feathers, medicinal plants, and tropical fruits.

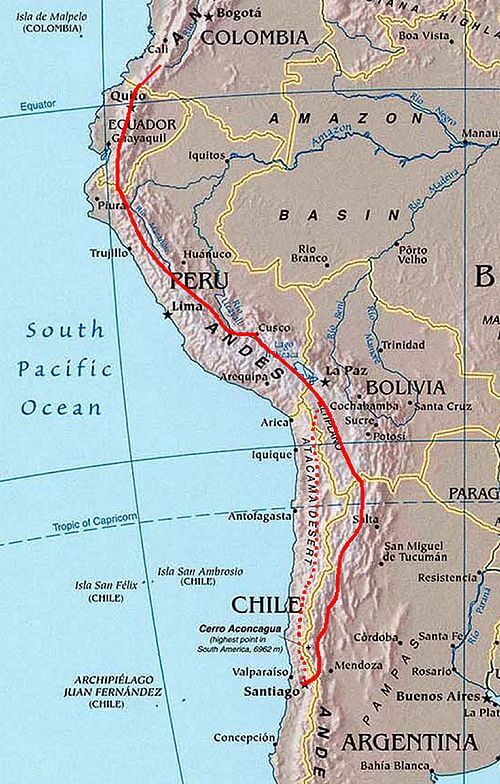

General map of the Great Inca Road.

Monuments Along the Sacred Path

The Qhapaq Ñan connects an extraordinary constellation of archaeological sites, each revealing different aspects of Inca civilization and their interactions with the peoples they conquered. These locations serve as waypoints in understanding how the road system functioned as both infrastructure and sacred landscape.

Machu Picchu, perched at 2,430 meters (7,970 feet) above sea level, represents perhaps the most spectacular achievement of Inca urban planning. Built during Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui's reign in the 15th century, this citadel demonstrates the Inca ability to create sophisticated settlements in seemingly impossible locations. The site's terraced agricultural areas, precisely aligned temples, and integrated water systems showcase technologies that were refined and disseminated throughout the empire via the road network.

At Saqsayhuamán, towering above Cusco at 3,701 meters (12,142 feet), massive limestone blocks weighing over 100 tons fit together with precision that continues to baffle engineers. The fortress's zigzag walls and strategic positioning exemplify how the Incas integrated defensive architecture with ceremonial spaces, creating monuments that served multiple functions within their complex society.

Ingapirca, Ecuador's most significant Inca site, illustrates how the empire adapted to local conditions and cultures. The elliptical Temple of the Sun demonstrates Inca astronomical knowledge while respecting existing Cañari architectural traditions. This cultural synthesis, repeated throughout the empire, was facilitated by the communication and administrative capabilities that the road network provided.

Beyond these major centers, the Qhapaq Ñan connects countless other remarkable sites that reveal the network's true scope and sophistication. Choquequirao, positioned at 3,050 meters (10,010 feet) above the thundering Apurímac River, serves as Machu Picchu's "sister city." Often called the "sister city" of Machu Picchu due to its similar structure and architecture, the site consists of an extensive complex of buildings and agricultural terraces built around the Sunch'u Pata, the truncated hilltop, on a steep mountainside. This sprawling complex, still partially buried beneath centuries of jungle growth, required multiple days of treacherous hiking to reach, suggesting it served as a sacred retreat for the highest echelons of Inca society.

Puyupatamarca or Phuyupatamarca is an archaeological site along the Inca Trail in the Urubamba Valley of Peru. Due to its altitude of roughly 3,600 meters (11,811 feet), it is known as "La Ciudad entre la Niebla" ("The City Above the Clouds"). This ethereal site features five small stone baths that continue to receive fresh mountain water during the rainy season, demonstrating the Inca mastery of hydraulic engineering at extreme altitudes. The terraced structures seem to float above the cloud line, creating a mystical atmosphere that likely enhanced their ceremonial significance.

Pikillaqta represents a fascinating example of pre-Inca influence on the road system. Pikillaqta is one of the most famous pre-Inca archaeological sites. It is unique because it predates the Inca civilization, yet its advanced infrastructure had a profound influence on later Inca architecture. The Wari, who built Pikillaqta, were one of the first Andean cultures to develop an expansive urban center. The Inca incorporated this sophisticated Wari site into their network, demonstrating their pragmatic approach to empire-building through adaptation rather than destruction.

Raqchi, located in Peru's southern highlands, showcases the impressive scale of Inca religious architecture. The site features the massive Temple of Wiracocha, whose walls originally rose 12 meters (39 feet) high, supported by a central row of circular columns—unique in Inca architecture. Raqch'i is located on a prominent ridge overlooking the surrounding valley, which provides a natural defensive position. Just beyond the wall, there is a large dry moat running along the edge of the ridge the site is situated on, illustrating how the Incas integrated ceremonial and military functions within their strategic network.

The Rhythm of Imperial Life

Daily life along the Qhapaq Ñan followed rhythms established by imperial decree and natural cycles. Llamas, domesticated & still used as pack animals, carried loads of up to 35 kilograms (77 pounds) while traveling at steady paces suited to high-altitude conditions. Unlike their relatives, alpacas are not pack animals; instead, they are prized for their exceptionally fine wool, which was reserved for imperial textiles and religious ceremonies.

The famous chasqui relay system transformed the roads into an information superhighway. These trained runners could carry messages across the empire faster than any existing communication system until the advent of the telegraph era. Stationed at tambos (way stations) spaced approximately every 6-7 kilometers (3.7-4.3 miles), chasquis memorized complex quipu (knotted string) records and verbal messages, then sprinted to the next station where fresh runners continued the relay.

Administrative efficiency depended on this communication network. Tax obligations, recorded on quipus, traveled from remote provinces to Cusco, while imperial edicts returned along the same routes. Census information, agricultural reports, and military intelligence flowed continuously along these pathways, enabling the centralized government to manage a territory larger than the Roman Empire at its peak.

Sacred Geography and Spiritual Highways

The Qhapaq Ñan served functions far beyond administrative convenience. In Andean cosmology, travel itself held sacred significance, and certain routes connected huacas (sacred sites) in patterns that reflected celestial movements and seasonal cycles. Pilgrims journeyed along these pathways to participate in ceremonies at mountaintop shrines, underground temples, and sacred springs.

Many roads are aligned with astronomical phenomena. The Inca precisely oriented their capital city, and extending outward, major routes followed directions that corresponded to important stars, constellations, and solar observations. During solstices and equinoxes, shadows cast by roadside markers would indicate specific directions or mark ceremonial times.

The integration of practical and spiritual purposes exemplifies Inca thinking, where the material and sacred worlds intertwined seamlessly. A road built to transport goods also served to connect communities with their spiritual landscape, reinforcing imperial ideology while respecting local religious traditions.

Legacy in Stone and Memory

Today, the Qhapaq Ñan exists simultaneously as an ancient monument and a living heritage. Indigenous communities throughout the Andes continue to use segments of the original roads for daily transportation, maintaining connections to their ancestral territories and traditional practices. During annual festivals, processions still follow ancient routes between communities, carrying forward ceremonies that predate the Inca Empire while incorporating Catholic elements introduced during colonial times.

Modern conservation efforts face the delicate challenge of preserving archaeological integrity while supporting communities whose cultural identity remains deeply intertwined with these sites. An extraordinary pre-Hispanic road network is facing development pressure and environmental degradation, making international cooperation essential for preservation.

Climate change poses additional threats, as changing precipitation patterns affect high-altitude sections while coastal development impacts lowland routes. The same adaptability that enabled Inca engineers to build across diverse environments now inspires contemporary efforts to strike a balance between preservation and sustainable development.

Conclusion: Pathways Through Time

The Qhapaq Ñan stands as a testament to what human societies can achieve when ambition aligns with a sophisticated understanding of both natural systems and social organization. More than an impressive feat of engineering, these roads represent a holistic approach to landscape management that integrates transportation, communication, spiritual practice, and ecological stewardship.

As we face contemporary challenges of connecting diverse communities while respecting environmental limits, the Inca example offers valuable insights. Their success derived not from dominating nature but from working with it, creating infrastructure that enhanced rather than destroyed the landscapes it traversed. The Qhapaq Ñan reminds us that the greatest monuments are those that continue serving their communities long after their builders have passed into memory, carrying forward not just physical pathways but the wisdom embedded in their stones.