Guardians of the Andes: South America's Ice Fields and Mountain Glaciers

South America hosts one of the world's most extensive and diverse glacial systems, containing approximately 99% of all tropical glaciers on Earth. Stretching along the spine of the Andes Mountains, this remarkable glacial network encompasses nearly every type of glacial environment.

From Tropics to Antarctica: The Complete Glacial Systems of South America

The South American continent hosts one of the world's most extensive and diverse glacial systems outside of Antarctica and Greenland, containing approximately 99% of all tropical glaciers on Earth, as well as some of the largest temperate ice fields in the Southern Hemisphere. Stretching along the spine of the Andes Mountains from Venezuela in the north to Chile and Argentina in the south, this remarkable glacial network spans over 7,000 kilometers (4,350 miles). It encompasses nearly every type of glacial environment found on the planet. From small tropical glaciers perched on equatorial volcanoes to massive Patagonian ice fields that rival those of Alaska, South America's glaciers represent a critical component of the global cryosphere, serving as vital freshwater reservoirs for hundreds of millions of people.

The continent's glacial diversity reflects its extraordinary geographic range, encompassing tropical, subtropical, temperate, and subpolar climatic zones. This latitudinal span creates unique opportunities to study how glaciers respond to different environmental conditions and climate forcings, making South America an invaluable natural laboratory for glaciological research and climate change studies.

Geographic Distribution and Major Glacial Regions

South America's glaciers are primarily concentrated along the Andes Mountains, with smaller glacial areas also found on isolated peaks and in the continent's extreme south. The glacial distribution can be divided into several distinct regions, each characterized by unique climatic conditions, geological settings, and glacial types.

Tropical Andes (10°N to 18°S)

The northern extent of South American glaciation begins in the Venezuelan Andes, where small glaciers cling to peaks above 4,800 meters (15,748 feet). The Sierra Nevada de Mérida contains Venezuela's only remaining glaciers, primarily on Pico Humboldt at 4,942 meters (16,214 feet) and Pico Bolívar at 4,978 meters (16,332 feet).

Moving south, Colombia's glaciated peaks include several stratovolcanoes and high mountain massifs. The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, a remote coastal range, supports glaciers on Pico Cristóbal Colón and Pico Simón Bolívar, both of which reach approximately 5,730 meters (18,799 feet). The Cordillera Oriental contains glaciated volcanoes, including Nevado del Ruiz at 5,321 meters (17,457 feet) and Nevado del Tolima at 5,215 meters (17,109 feet).

Ecuador's glacial systems are concentrated on high volcanic peaks along the Avenue of Volcanoes. Major glaciated peaks include Chimborazo at 6,263 meters (20,548 feet), Cotopaxi at 5,897 meters (19,347 feet), and Cayambe at 5,790 meters (18,996 feet). These equatorial glaciers represent some of the highest tropical ice in the world.

Peru contains the largest concentration of tropical glaciers globally, with over 70% of the world's tropical ice. The Cordillera Blanca alone contains more than 600 glaciers, including those surrounding Huascarán at 6,768 meters (22,205 feet), Peru's highest peak. Other significant glaciated ranges include the Cordillera Huayhuash and the Cordillera Vilcanota, as well as numerous isolated peaks throughout the Peruvian Andes.

Bolivia's glacial coverage is concentrated in the Cordillera Real and Cordillera Occidental, with notable ice on Sajama at 6,542 meters (21,463 feet) and the Illimani massif at 6,438 meters (21,122 feet). These high-altitude glaciers are crucial water sources for the densely populated Altiplano region.

Subtropical and Central Andes (18°S to 35°S)

The central Andes of Chile and Argentina contain numerous high-altitude glaciers, though coverage is generally more sparse than in tropical regions due to arid conditions. The Cordillera de los Andes reaches its greatest heights in this region, with Aconcagua at 6,962 meters (22,841 feet), supporting several small glaciers despite the relatively dry climate.

Significant glaciated peaks in this region include Ojos del Salado at 6,893 meters (22,615 feet), Llullaillaco at 6,739 meters (22,110 feet), and numerous other peaks exceeding 6,000 meters (19,685 feet). The extreme altitude compensates for the arid climate, allowing glacier formation above approximately 5,500 meters (18,045 feet).

Patagonian Andes (35°S to 55°S)

Southern South America contains the continent's most extensive glacial systems, including the Northern Patagonian Ice Field and Southern Patagonian Ice Field. These massive ice caps represent the largest temperate ice bodies in the Southern Hemisphere outside of Antarctica.

The Northern Patagonian Ice Field covers approximately 4,200 square kilometers (1,622 square miles) and feeds numerous outlet glaciers, including San Rafael Glacier, which terminates in a tidal lagoon. The ice field sits astride the continental divide, with glaciers flowing both eastward toward Argentina and westward toward the Pacific Ocean in Chile.

The Southern Patagonian Ice Field, spanning approximately 13,000 square kilometers (5,019 square miles), is one of the world's largest ice caps outside the polar regions. Major outlet glaciers include the Perito Moreno, Upsala, Spegazzini, and Viedma glaciers in Argentina, as well as the Tyndall, Grey, and Pio XI glaciers in Chile. The ice field reaches thicknesses exceeding 1,500 meters (4,921 feet) in some areas.

Fuegian Andes and Isolated Ice Fields

The southernmost glacial systems include the Cordillera Darwin on Tierra del Fuego, containing numerous small glaciers and ice caps. The Gran Campo Nevado ice field in southern Chile covers approximately 200 square kilometers (77 square miles) and represents one of the southernmost continental ice masses.

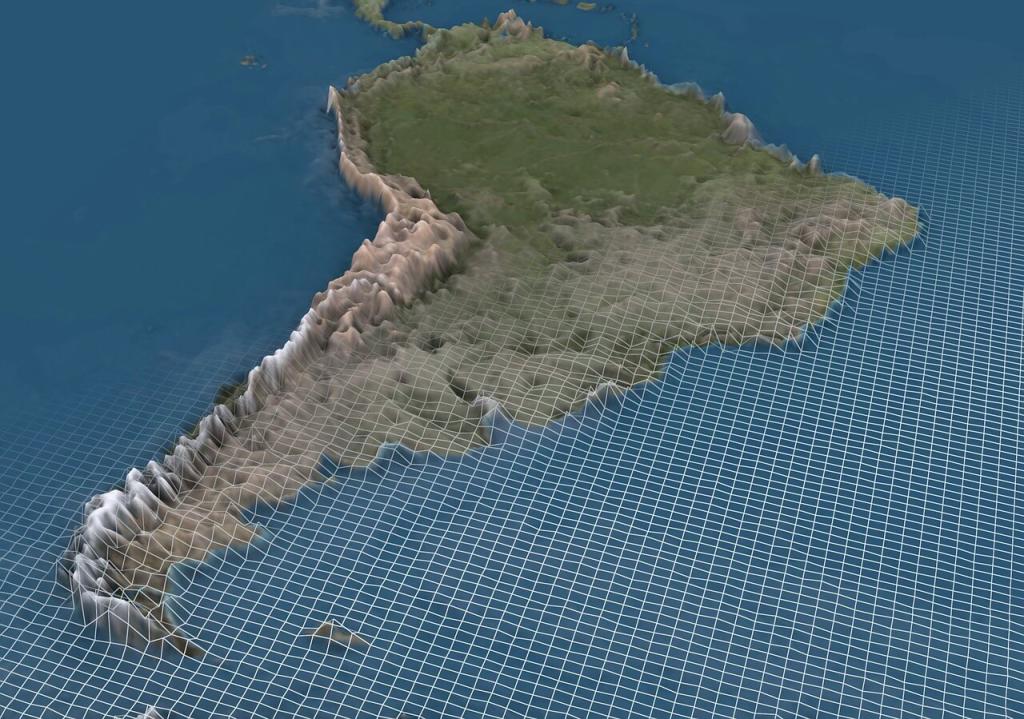

South America Andes 3D Map.

Glacial Characteristics and Formation

South America's glacial diversity encompasses virtually every type of glacier found on Earth. Tropical glaciers in the northern Andes exist under unique conditions where temperatures remain near freezing year-round, with minimal seasonal variation but significant diurnal temperature fluctuations. These glaciers typically undergo daily freeze-thaw cycles and are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations.

Temperate glaciers dominate the Patagonian region, where abundant precipitation from Pacific storm systems provides substantial snowfall accumulation. These glaciers often extend to sea level and may terminate in freshwater or tidal environments, creating spectacular calving fronts and contributing significantly to sea level rise.

Polar-type glaciers are found on the highest peaks and in the driest regions, where temperatures remain consistently below freezing throughout the year. These glaciers experience minimal surface melting and may preserve climate records spanning centuries or millennia.

The formation and evolution of South American glaciers reflect complex interactions between topography, climate, and ocean-atmosphere dynamics. The Andes Mountains create strong orographic effects, forcing moisture-laden air masses to rise and deposit snow on windward slopes. The presence of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile creates one of the world's most extreme precipitation gradients, with some areas receiving less than 1 millimeter (0.04 inches) of annual precipitation while nearby mountain peaks accumulate several meters of snow.

Climate Controls and Regional Variations

South America's vast latitudinal extent subjects its glaciers to diverse climatic influences. El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events significantly impact glacial mass balance, particularly in the tropical Andes, where El Niño events typically bring reduced precipitation and accelerated melting, while La Niña events may enhance accumulation.

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) influences precipitation patterns in northern South America, with its seasonal migration affecting the intensity of wet and dry seasons. South American Monsoon patterns impact glaciers in the central and southern tropical Andes, with most precipitation occurring during the austral summer months (December through March).

Westerly wind patterns dominate the Patagonian climate, bringing moisture from the Pacific Ocean and creating the high precipitation rates necessary to sustain the massive ice fields. These winds strengthen during the austral winter, contributing to the seasonal accumulation patterns that characterize temperate glacial systems.

The influences of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans create distinct precipitation patterns on the eastern and western Andean slopes. The rain shadow effect creates dramatically different conditions across the mountain range, with some eastern slopes receiving abundant moisture while western slopes in certain regions remain extremely arid.

Hydrological Significance

South American glaciers serve as crucial freshwater reservoirs for the continent's major river systems, providing water security for over 100 million people. Glacial meltwater contributes significantly to river discharge in the Amazon, Orinoco, Magdalena, and numerous Pacific-draining rivers.

In Peru, glacial meltwater provides approximately 40% of the dry season flow for rivers serving Lima, a metropolitan area of over 10 million people. High-altitude glaciers throughout the tropical Andes provide critical water supplies for mining operations, hydroelectric power generation, and agricultural irrigation in some of the world's most arid regions.

The Patagonian ice fields contribute a substantial amount of freshwater to the Southern Ocean and significantly influence regional ocean circulation patterns. Glacial discharge from these ice fields has been increasing due to climate warming, contributing measurably to global sea level rise.

Seasonal water storage provided by glaciers is particularly important in regions with distinct wet and dry seasons. Glaciers accumulate snow during wet periods and release meltwater during dry periods, providing natural water regulation that supports ecosystems and human communities throughout the year.

Biodiversity and Ecological Significance

South American glacial environments support remarkable biodiversity, which is adapted to extreme high-altitude conditions. The páramo ecosystems surrounding tropical glaciers contain numerous endemic plant species, including distinctive cushion plants, rosette species, and specialized grasses.

Notable flora includes the Espeletia species (frailejones), which create characteristic landscapes in the Colombian and Venezuelan páramos, and Polylepis forests that survive at elevations exceeding 4,500 meters (14,764 feet) in Peru and Bolivia. These high-altitude forests represent some of the world's highest woodland ecosystems and provide crucial habitat for specialized fauna.

Alpine wildlife includes several endemic species, such as the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus) and the vicuña (Vicugna vicugna), as well as numerous bird species adapted to high-altitude environments. The Andean condor (Vultur gryphus) utilizes thermal updrafts along glaciated peaks and serves as an important scavenger in these ecosystems.

Glacial lakes formed by glacial retreat support unique aquatic ecosystems and serve as critical habitat for waterbirds and endemic fish species. Many of these lakes have formed only recently as glaciers have retreated, creating new ecological niches and opportunities for species colonization.

Marine ecosystems in Patagonia are significantly influenced by glacial discharge, which provides nutrients and affects water temperature and salinity. The mixing of glacial meltwater with ocean water creates productive environments that support important fisheries and marine mammal populations.

Historical Changes and Glacial Retreat

South American glaciers have experienced dramatic changes over the past century, with retreat rates accelerating significantly since the 1980s. Tropical glaciers have been particularly affected, with some estimates suggesting that Andean glaciers have lost 20-50% of their area since the 1970s.

Colombian glaciers have experienced some of the most dramatic losses globally, with total glaciated area declining from approximately 100 square kilometers (39 square miles) in 1950 to less than 50 square kilometers (19 square miles) today. Several small glaciers have disappeared entirely, and the remaining ice is fragmented into isolated patches.

Peruvian glaciers in the Cordillera Blanca have retreated substantially, with some studies documenting area losses exceeding 25% since 1970. The Quelccaya Ice Cap, one of the largest tropical ice caps, has been retreating at accelerating rates, exposing plant material that provides insights into past climate conditions.

The Patagonian ice fields have contributed significantly to global sea level rise, with recent studies indicating mass loss rates that exceed those of most other glacial regions. Major outlet glaciers such as Upsala and Jorge Montt have experienced dramatic retreat and thinning, with some glaciers retreating several kilometers in just a few decades.

Equilibrium line altitudes have risen throughout South America, with the greatest changes observed in tropical regions where warming has been most pronounced. In some areas, the equilibrium line has increased 150-200 meters (492-656 feet) since the mid-20th century.

Contemporary Research and Monitoring

Current research on South American glaciers employs a diverse range of methodologies, including satellite remote sensing, field-based glaciological studies, paleoclimate reconstruction, and numerical modeling. International cooperation has intensified, with programs such as the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) project providing comprehensive glacial inventories.

Ice core research has provided valuable paleoclimate records, particularly from high-altitude sites such as Quelccaya Ice Cap and Sajama. These records reveal details about past climate variability, volcanic eruptions, and changes in atmospheric composition extending back several millennia.

Mass balance studies on representative glaciers provide direct measurements of glacial response to climate variability. Long-term monitoring programs in Peru, Colombia, and Patagonia have established some of the longest records of tropical and temperate glacial mass balance in the Southern Hemisphere.

Glacial lake studies have become increasingly important as glacier retreat creates new lakes that may pose glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) hazards. Remote sensing and field studies monitor lake formation, expansion, and potential instability.

Modeling efforts integrate observational data with climate projections to assess future glacial changes and their implications for water resources. These studies are crucial for water resource planning and climate change adaptation strategies.

Climate Change Impacts and Future Projections

Climate change is the primary driver of glacial retreat throughout South America, with warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns creating conditions that are incompatible with glacial persistence in many regions. Regional climate models project continued warming of 2-6°C (3.6-10.8°F) by 2100, with the greatest warming expected at high elevations.

Tropical glaciers are projected to experience the most severe impacts, with many small glaciers likely to disappear within the next 20 to 50 years. The combination of rising temperatures and potential changes in precipitation seasonality could eliminate glacial conditions below 5,500 meters (18,045 feet) in many tropical regions.

Patagonian ice fields face different challenges, with warming temperatures potentially offset by increased precipitation in some scenarios. However, marine-terminating glaciers are particularly vulnerable to ocean warming and may undergo rapid retreat due to marine ice sheet instability processes.

Water resource implications are profound, with glacial meltwater contributing significantly to river discharge in many arid and semi-arid regions. The transition from glacial to rainfall-dominated hydrology will fundamentally alter water availability patterns and require significant adaptation measures.

Sea level rise contributions from South American glaciers are projected to continue and potentially accelerate, particularly from the large Patagonian ice fields. Recent estimates suggest these ice masses could contribute 5-15 centimeters (2-6 inches) to global sea level rise by 2100 under high warming scenarios.

Socioeconomic Significance and Cultural Importance

South American glaciers hold profound cultural significance for Indigenous communities throughout the Andes. Andean cosmology traditionally views high peaks and glaciers as sacred entities (apus) that provide spiritual protection and serve as a source of water resources. The potential loss of glacial ice represents not only environmental degradation but also cultural and spiritual loss.

Economic impacts of glacial retreat are already evident in several regions. Hydroelectric power generation in many Andean countries heavily relies on glacial meltwater, with some facilities experiencing reduced capacity during dry seasons as glacial contributions decline.

Agricultural systems throughout the Andes have developed over millennia to utilize glacial meltwater for irrigation. Changes in water availability threaten traditional farming practices and food security for rural communities that depend on high-altitude agriculture.

The tourism industry generates significant revenue from glacier-related attractions, including trekking, mountaineering, and scenic tourism. Iconic destinations, such as the Perito Moreno Glacier in Argentina and glaciated peaks in Peru, attract millions of visitors annually, contributing substantially to local and national economies.

Mining operations in high-altitude regions depend on glacial meltwater for ore processing and dust suppression. Changes in water availability may require significant infrastructure investments and operational modifications.

Natural Hazards and Risk Management

South American glaciers pose various natural hazards that affect downstream communities and infrastructure. Glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) represent one of the most significant hazards, particularly in Peru, where numerous glacial lakes have formed as glaciers retreat.

Ice avalanches from steep, glaciated slopes can trigger debris flows and pose a threat to communities in mountain valleys. The 1970 Huascarán avalanche in Peru, triggered by an earthquake, killed approximately 20,000 people and remains one of the deadliest natural disasters in South American history.

Volcanic-glacial interactions create unique hazards in regions where active volcanoes are located within glaciated areas. Lahars (volcanic mudflows) can form when volcanic heat rapidly melts glacial ice, creating fast-moving debris flows that threaten downstream areas. Colombian volcanoes such as Nevado del Ruiz have produced devastating lahars that have caused thousands of casualties.

Climate change adaptation strategies include early warning systems for glacial hazards, infrastructure relocation in high-risk areas, and the development of alternative water sources. International cooperation supports capacity building and technology transfer for hazard monitoring and risk reduction.

Water Resource Management and Adaptation

The changing contribution of glacial meltwater to river systems requires comprehensive water resource management strategies throughout South America. Integrated watershed management approaches consider the full range of water sources and uses, incorporating climate change projections and glacial retreat scenarios to inform their planning.

Alternative water sources being developed include groundwater exploitation, rainwater harvesting, desalination facilities, and improved water storage infrastructure. Peru's National Institute for Glacier and Mountain Ecosystem Research (INAIGEM) leads efforts to understand glacial changes and develop adaptation strategies.

Ecosystem-based adaptation approaches utilize natural systems to enhance water security and reduce climate risks. Wetland restoration in high-altitude areas can increase water storage capacity and provide ecosystem services that complement traditional infrastructure approaches.

Regional cooperation through organizations such as the Andean Community facilitates the sharing of information and the coordinated management of transboundary water resources affected by glacial changes.

Conservation Efforts and Protected Areas

South American countries have established numerous protected areas that encompass important glacial systems. Huascarán National Park in Peru protects a significant portion of the Cordillera Blanca and its glaciers, while Los Glaciares National Park in Argentina preserves portions of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field.

International designations such as UNESCO World Heritage Sites and Biosphere Reserves provide additional protection for glaciated areas. The Sangay National Park in Ecuador and Los Glaciares National Park in Argentina have received World Heritage status, recognizing their outstanding universal value.

Community-based conservation initiatives involve local communities in monitoring glaciers and protecting ecosystems. Traditional knowledge systems provide valuable insights into environmental changes and complement scientific monitoring programs.

Research and monitoring networks facilitate the sharing of data and collaborative research efforts. The World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) coordinates global glacier observations, with significant contributions from researchers and institutions in South America.

Regional and Global Context

South American glaciers play a crucial role in the global climate and ocean systems. Paleoclimate records from Andean ice cores provide insights into past climate variability and help validate climate models used for future projections.

The contributions of South American glaciers to global sea level rise are significant and increasing. The Patagonian ice fields are among the largest contributors to sea level rise, alongside the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

Biodiversity hotspots associated with glacial environments in South America contain numerous endemic species and represent important reservoirs of genetic diversity. These ecosystems provide valuable ecosystem services and support unique evolutionary processes.

Scientific collaboration between South American institutions and international research organizations has significantly enhanced the understanding of glacial processes and the impacts of climate change. These partnerships facilitate technology transfer and capacity building, benefiting both regional and global research efforts.

Future Research Directions

Emerging research priorities for South American glaciers include improved understanding of ice dynamics in tropical environments, better quantification of groundwater-glacier interactions, and enhanced modeling of coupled climate-glacier-hydrology systems.

Remote sensing technologies continue to advance, providing new capabilities for monitoring glacial changes at high temporal and spatial resolution. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and satellite-based interferometry offer promising approaches for detailed glacial studies in remote and dangerous terrain.

Interdisciplinary research integrating glaciology, hydrology, ecology, and social sciences provides a holistic understanding of human-environment interactions in glaciated watersheds. These approaches are essential for developing effective adaptation and management strategies.

Early warning systems for glacial hazards require continued technological development and international cooperation. Integration of monitoring networks, communication systems, and community preparedness programs can significantly reduce risks to vulnerable populations.

Conclusion

South America's glacial systems represent one of the world's most diverse and significant ice masses, spanning from tropical high-altitude environments to massive temperate ice fields. These glaciers serve as critical freshwater reservoirs for over 100 million people, support unique ecosystems, preserve valuable paleoclimate records, and contribute substantially to global sea level rise.

The rapid retreat of South American glaciers in response to climate change represents one of the most visible and consequential impacts of global warming. The loss of glacial ice poses a significant threat to water security for major population centers, alters ecosystem dynamics, increases natural hazard risks, and erodes important cultural and spiritual resources for Indigenous communities.

The complexity and diversity of South American glacial systems provide valuable insights into how ice masses respond to different climate forcings and environmental conditions. Research from these glaciers contributes significantly to global understanding of glacier-climate interactions and helps improve projections of future changes.

The future of South America's glaciers largely depends on global efforts to mitigate climate change through reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Even under optimistic scenarios, substantial additional glacial retreat is inevitable, requiring comprehensive adaptation strategies and international cooperation to address the cascading impacts on water resources, ecosystems, and human communities.

The story of South America's glaciers serves as both a warning about the pace and magnitude of climate change impacts and a testament to the resilience of natural systems and human communities. Their preservation and sustainable management represent critical challenges that will require continued scientific research, international cooperation, and innovative approaches to climate change adaptation and water resource management.

As these ancient ice masses continue their retreat toward uncertain futures, they leave behind transformed landscapes, altered hydrological systems, and profound lessons about the interconnectedness of climate, ice, water, and human society in one of the world's most glacially diverse continents.

Addendum: Current Glacial Inventory of South America

Venezuela - Sierra Nevada de Mérida

Active Glaciers:

- Humboldt Glacier - Pico Humboldt (4,942m/16,214ft) - Last remaining glacier

- Bolívar Glacier - Pico Bolívar (4,978m/16,332ft) - Severely retreated, near extinction

Status: Only 1-2 small glaciers remain; total area <1 km²

Colombia

Active Glaciated Peaks:

- Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta: Pico Cristóbal Colón, Pico Simón Bolívar (5,730m/18,799ft)

- Nevado del Ruiz (5,321m/17,457ft) - Multiple small glaciers

- Nevado del Tolima (5,215m/17,109ft)

- Nevado Santa Isabel (4,965m/16,289ft)

- Nevado del Huila (5,364m/17,598ft)

Total Glaciated Area: ~37 km² (14 sq mi)

Ecuador - Avenue of Volcanoes

Major Glaciated Peaks:

- Chimborazo (6,263m/20,548ft) - Largest glacial coverage

- Cotopaxi (5,897m/19,347ft) - Multiple outlet glaciers

- Cayambe (5,790m/18,996ft) - Equatorial glacier

- Antisana (5,753m/18,875ft)

- Altar (5,319m/17,451ft)

- Illiniza Sur (5,248m/17,218ft)

- Carihuairazo (5,020m/16,470ft)

Total Glaciated Area: ~118 km² (46 sq mi)

Peru - World's Largest Tropical Glacial Coverage

Major Glaciated Cordilleras:

Cordillera Blanca:

- Huascarán Sur (6,768m/22,205ft) - Peru's highest peak

- Yerupajá (6,635m/21,768ft)

- Alpamayo (5,947m/19,511ft)

- Artesonraju (6,025m/19,767ft)

- Over 600 individual glaciers

Cordillera Huayhuash:

- Yerupajá (6,635m/21,768ft)

- Siula Grande (6,344m/20,814ft)

- Jirishanca (6,126m/20,098ft)

Cordillera Vilcanota:

- Ausangate (6,384m/20,945ft)

- Quelccaya Ice Cap - Largest tropical ice cap

Other Major Ranges:

- Cordillera Central, Cordillera Oriental, Cordillera Occidental

- Total Glaciated Area: ~1,298 km² (501 sq mi)

Bolivia

Major Glaciated Peaks:

- Sajama (6,542m/21,463ft) - Bolivia's highest peak

- Illimani (6,438m/21,122ft) - La Paz water source

- Illampu (6,368m/20,892ft)

- Huayna Potosí (6,088m/19,974ft)

- Chacaltaya - Former ski area, glacier extinct in 2009

Total Glaciated Area: ~326 km² (126 sq mi)

Chile and Argentina - Central Andes

Major Glaciated Peaks:

- Aconcagua (6,961m/22,838ft) - Highest peak in the Americas

- Ojos del Salado (6,893m/22,615ft) - Highest active volcano

- Llullaillaco (6,739m/22,110ft)

- Mercedario (6,720m/22,047ft)

- Tupungato (6,635m/21,768ft)

Patagonian Ice Fields

Northern Patagonian Ice Field (Campo de Hielo Norte):

- Total Area: ~4,200 km² (1,622 sq mi)

- Major Outlet Glaciers:

- San Rafael Glacier (tidewater)

- San Quintín Glacier

- Steffen Glacier

- Nef Glacier

Southern Patagonian Ice Field (Campo de Hielo Sur):

- Total Area: ~13,000 km² (5,019 sq mi)

- Argentine Side Major Glaciers:

- Perito Moreno Glacier

- Upsala Glacier

- Spegazzini Glacier

- Viedma Glacier

- Chilean Side Major Glaciers:

- Tyndall Glacier

- Grey Glacier

- Pio XI Glacier (the largest in South America)

- O'Higgins Glacier

Fuegian and Southern Ice Fields

- Cordillera Darwin Ice Field: ~200 km² (77 sq mi)

- Gran Campo Nevado: ~200 km² (77 sq mi)

- Numerous smaller ice caps and glaciers

Summary Statistics

- Total Glaciated Area: ~25,000+ km² (9,650+ sq mi)

- Countries with Glaciers: 6 (Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina)

- Major Ice Fields: 4 (Northern/Southern Patagonian, Gran Campo Nevado, Cordillera Darwin)

- Glaciated Peaks >6,000m: Over 100

- Tropical Glaciers: ~99% of the world's total

- Contribution to Sea Level Rise: ~0.15mm/year (increasing)