The Arid Diagonal: South America's Great Drylands

South America's Arid Diagonal is a vast belt of arid and semi-arid ecosystems extending from coastal Peru to southeastern Argentina and northeastern Brazil. Despite extreme aridity, the diagonal harbors remarkable biodiversity with high endemism levels, though it faces conservation challenges.

South America's Arid Diagonal: A Continent-Spanning Belt of Drylands

Introduction and Geographic Extent

The South American Arid Diagonal (SAAD) comprises a chain of successive deserts and drylands that stretch diagonally across South America in a northwest-to-southeast direction. It is an extensive and continuous arid strip that starts at the Pacific Ocean in Peru (south of Ecuador) and runs southeastward approximately 7,000 kilometers (4,350 miles) to the Atlantic Ocean on the northeastern coast of Patagonia (43°S). The diagonal includes three continental deserts—the Argentine Monte, High Monte, and Central Andean Dry Puna—and two coastal deserts—the Atacama and Sechura—all of which belong to the Neotropical deserts biogeographic region within the Desert Biome. This immense belt of arid and semi-arid ecosystems spans latitudes from 5°S to 50°S, encompassing portions of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Chile, and Argentina. The diagonal orientation distinguishes this feature from the more typical zonal pattern of deserts that run parallel to the equator at similar latitudes in both hemispheres.

French geographer Emmanuel de Martonne first articulated the concept of a South American Arid Diagonal in his seminal 1935 work. Subsequent scholars have refined and expanded this concept, with some researchers proposing the inclusion of northeastern Brazil's Caatinga region, creating what is sometimes referred to as two distinct "dry diagonals"—a western diagonal and an eastern diagonal. Together with Brazil's northeast drylands, the Arid Diagonal encompasses the drylands of Latin America, of which approximately 75% are affected by desertification.

Geological Origins and Climatic Drivers

The Arid Diagonal originated during the Neogene period (approximately 23 to 2.6 million years ago) as a consequence of major geological and oceanographic changes that fundamentally altered South America's climate patterns. Two pivotal events drove the formation and intensification of continental aridity: the uplift of the Andes Mountains and the establishment of cold oceanic currents along South America's western coast.

The Andean orogeny, driven by the subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South American Plate, created a massive north-south trending mountain barrier along the continent's western margin. As the Andes rose, they progressively blocked the westward flow of moisture-laden air from the Amazon Basin in tropical latitudes and the eastward penetration of Pacific moisture in temperate latitudes. This rain shadow effect intensified throughout the Miocene and Pliocene epochs (approximately 5 to 10 million years ago) as the mountains reached their modern elevations, exceeding 6,900 meters (22,638 feet) at Aconcagua. The result was a dramatic aridification of western and central Argentina, transforming once-mesic environments into the arid shrublands and grasslands that characterize the region today.

Simultaneously, the permanent intrusion of cold Antarctic waters established the Humboldt Current (also called the Peru Current), which flows northward along South America's Pacific coast from Chile to Ecuador. This cold eastern boundary current, driven by the South Pacific subtropical gyre and intensified by coastal upwelling, profoundly influences climate along the entire western margin of South America. The cold water cools the overlying air, creating a stable atmospheric layer that suppresses convection and cloud formation. This process, combined with subsidence associated with the South Pacific High-pressure system, creates the extreme aridity of the Atacama and Sechura deserts. Mean annual precipitation in the hyperarid core of the Atacama is less than 1 millimeter (0.04 inches), with some locations experiencing decades without measurable rainfall.

In the southern portions of the Arid Diagonal, the climate is shaped by the mid-latitude westerlies that carry substantial moisture from the Pacific Ocean. However, as these air masses encounter the Andes, orographic lifting forces precipitation on the windward (Chilean) slopes, leaving the leeward eastern slopes and Argentine Patagonia in a pronounced rain shadow. The subtropical jet stream, positioned around 30°S and intensified during austral winter, enhances these westerlies, but the Andes effectively block moisture, resulting in semi-arid to arid conditions with precipitation gradients dropping sharply east of the cordillera.

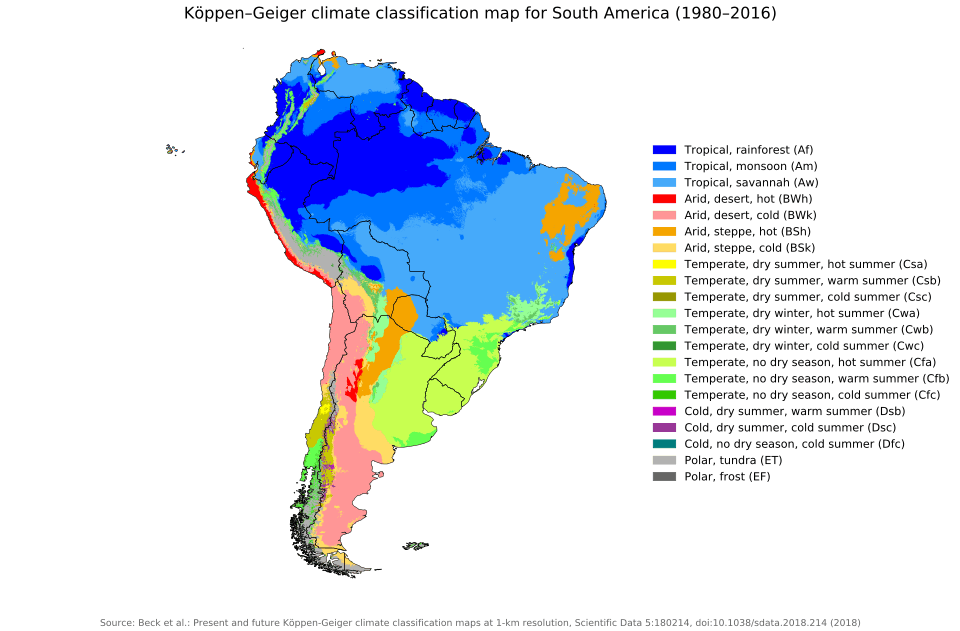

Climate classifications within the Arid Diagonal reflect this environmental diversity. Using the Köppen-Geiger system, the northern sections, including the Atacama and Sechura deserts, are classified as BWh (hot desert climate), characterized by minimal precipitation and high solar radiation. Southern portions, including the Patagonian Desert, transition to a BWk (cold desert climate), with cooler temperatures influenced by higher latitudes. Annual precipitation varies dramatically from less than 10 millimeters (0.4 inches) in hyperarid zones to 300 to 1,000 millimeters (11.8 to 39.4 inches) in semi-arid sectors, but potential evapotranspiration exceeds precipitation throughout, defining the arid and semi-arid conditions.

Major Desert Systems and Ecoregions

The Arid Diagonal encompasses several distinct desert systems and ecoregions, each with unique environmental conditions, evolutionary histories, and biological communities.

The Atacama Desert

The Atacama Desert, extending along approximately 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) of Chile's Pacific coast from near the Peruvian border to north of Santiago, ranks as Earth's driest non-polar desert. This hyperarid environment, covering approximately 105,000 to 128,000 square kilometers (40,540 to 49,420 square miles) when including the barren lower slopes of the Andes, has existed in an arid state for at least 3 million years, making it also one of the world's oldest deserts. The constant temperature inversion caused by the cold Humboldt Current and the strong Pacific anticyclone contributes to the extreme aridity.

Despite its reputation as lifeless, the Atacama harbors surprising biodiversity adapted to extreme conditions. Vegetation includes over 500 species characterized by extraordinary adaptations to aridity and high solar radiation. Fog-dependent lomas formations along the coast support seasonal herbaceous communities of annuals and geophytes, including species from the genera Nolana, Alstroemeria, and Cristaria, which rely on coastal fog (locally called camanchaca) for moisture. At higher elevations between 3,000 and 5,000 meters (9,843 to 16,404 feet), cushion plants such as Azorella compacta (llareta), one of the highest-growing woody species in the world, form dense mats 3 to 4 meters (9.8 to 13.1 feet) thick that concentrate and retain heat. Cacti, including columnar Echinopsis species (candelabro and cardón), can reach heights of 7 meters (23 feet). In years with sufficient precipitation, the "Atacama flowering" (desierto florido) transforms portions of the desert into carpets of wildflowers.

The fauna, though limited by extreme aridity, includes specialized desert-adapted species. Liolaemus lizards inhabit rocky areas, while the critically endangered Atacama toad (Rhinella atacamensis) persists in isolated wetlands. Mammals include the ashy chinchilla rat (Abrocoma cinerea), which builds urine-cemented latrines up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) high, and various species of leaf-eared mice (Phyllotis spp.). Birds visiting or residing in the desert include Andean flamingos (Phoenicoparrus andinus), which feed in high-altitude salt lakes. Along the coast, Humboldt penguins (Spheniscus humboldti) and various seabird species benefit from the productive upwelling ecosystem.

The Sechura Desert

The Sechura Desert, located in northwestern Peru along the Pacific coast, occupies approximately 188,735 square kilometers (72,870 square miles). Though classified as a desert due to low annual precipitation, the Sechura experiences unique influences from the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). During El Niño events, when warm water replaces the normally cold Humboldt Current, the region receives dramatically increased rainfall, transforming the landscape. Temporary wetlands appear, vegetation blooms, and wildlife populations surge. This boom-and-bust dynamic creates ecological patterns distinct from more consistently arid deserts.

Vegetation is sparse but includes low-lying shrubs, cacti (including various Opuntia species), succulents, and desert grasses adapted to long dry periods punctuated by occasional deluges. The extensive dune systems, composed of fine sand reaching impressive heights, create a dynamic landscape. Wildlife includes the Peruvian thick-knee (Burhinus superciliaris) and Peruvian tern (Sterna lorata), both species of conservation concern, along with various lizards, snakes, and desert-adapted rodents.

The Monte Desert

The Monte Desert, extending along the eastern Andean slopes of Argentina from approximately 24°S to 44°S, encompasses both the High Monte (covered in a previous article) and the Argentine, or Low Monte, ecoregion. Together they form a continuous belt of approximately 460,000 square kilometers (177,608 square miles). The Monte exhibits greater biodiversity than the surrounding deserts, reflecting its warm-temperate climate, varied topography ranging from sandy plains to rocky outcrops, and, in some areas, surprisingly nutrient-rich soils.

Vegetation is dominated by xerophytic shrubs, particularly species of Larrea (jarilla), and by xerophilous woodlands of Prosopis (algarrobo) along watercourses. Wildlife includes significant populations of Lama guanicoe (guanaco) and Dolichotis patagonum (Patagonian mara), as well as numerous endemic rodents. The endangered pink fairy armadillo (Chlamyphorus truncatus), found only in central Argentina, represents an icon of Monte endemism. Avian diversity includes Cyanoliseus patagonus (burrowing parrot), which excavates colonial nests in cliff faces, and Eudromia elegans (elegant crested tinamou).

The Patagonian Desert

The Patagonian Desert, shared by Argentina and Chile, covers approximately 670,000 square kilometers (258,688 square miles), making it Argentina's largest desert and the world's eighth largest. This cold desert, characterized by strong, persistent winds, barren steppes, and sparse vegetation, experiences relatively low temperatures year-round. The region lies in the rain shadow of the Southern Andes, with mean annual precipitation ranging from 100 to 200 millimeters (3.9 to 7.9 inches) in the driest interior locations.

Vegetation consists primarily of low shrubs and bunchgrasses, including species of Stipa, Poa, and Festuca, interspersed with cushion plants adapted to constant wind and cold. Despite harsh conditions, the Patagonian Desert supports populations of guanacos, Rhea pennata (Darwin's rhea or lesser rhea), Lycalopex culpaeus (culpeo fox), and various rodents and birds. The region's endemic and near-endemic species reflect millions of years of evolution in isolation.

The Puna and Prepuna

The high-altitude Puna, occupying the Andean plateau above approximately 3,500 meters (11,483 feet) in Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, and Peru, represents one of the harshest environments within the Arid Diagonal. This cold, arid highland experiences extreme diurnal temperature fluctuations, intense solar radiation, low oxygen levels, and minimal precipitation. Vegetation consists of low cushion plants, tussock grasses (Festuca and Stipa spp.), and scattered shrubs adapted to freezing temperatures and intense radiation.

The Prepuna, a transitional zone between the Monte and Puna at elevations from approximately 2,000 to 3,500 meters (6,562 to 11,483 feet), exhibits characteristics intermediate between these ecoregions. This ecotone harbors particularly high species richness resulting from the mixing of biotas from adjacent regions, with numerous endemic species occupying this narrow elevational band.

Biogeography and Biodiversity

The Arid Diagonal functions as both a barrier and a corridor in South American biogeography. As a barrier, it isolates the temperate and subtropical forests of Chile and southern Argentina from the Amazon Basin and Atlantic Forest, preventing dispersal of forest-dependent species and creating distinct evolutionary lineages on either side. Together with Quaternary glaciations in the Southern Andes, the diagonal has profoundly controlled the distribution of vegetation and fauna throughout Chile and Argentina for millions of years.

Paradoxically, at times the diagonal has served as a corridor, particularly during Pleistocene glacial maxima, when cooler, more humid conditions may have allowed the expansion of forest vegetation along mountain slopes, creating temporary connections between now-isolated forest blocks. The "Pleistocene Arc" hypothesis proposes that seasonally dry tropical forest fragments—currently distributed across the Caatinga, Chiquitanía, Misiones, and Subandean Piedmont—were connected during Pleistocene glacial periods, allowing biotic exchange before fragmenting again during interglacials.

Biodiversity within the Arid Diagonal exhibits remarkable patterns of endemism, particularly among plants, invertebrates, and small vertebrates with limited dispersal abilities. Research in the northern Monte indicates that approximately 10% of insect genera and 35% of insect species are endemic. Among plants, hundreds of species occur exclusively within portions of the diagonal, having evolved specialized adaptations to local soil chemistry, moisture regimes, and temperature patterns.

The transition zones between the Arid Diagonal and adjacent mesic ecosystems harbor particularly high species diversity and endemism. The interface between the High Monte and the Southern Andean Yungas cloud forests, for example, creates steep environmental gradients that support unique assemblages of species with narrow ecological tolerances. Similarly, the boundaries between the diagonal and the Chaco, Espinal, and Patagonian steppe contain disproportionate shares of endemic species relative to core areas of these ecoregions.

Human Dimensions and Conservation

Indigenous peoples have inhabited regions within the Arid Diagonal for millennia, developing sophisticated adaptations to arid environments. Archaeological evidence traces human settlements in the Atacama territory back to the late Pleistocene. Groups including the Atacameño, Diaguita, and numerous Patagonian peoples developed extensive knowledge of water sources, seasonal patterns, and plant and animal resources. Many contemporary communities continue traditional livelihoods adapted to aridity, including pastoralism with llamas, alpacas, and goats, and cultivation of drought-tolerant crops in irrigated oases.

Modern human activities pose significant threats to Arid Diagonal ecosystems. Overgrazing by domestic livestock represents the most widespread impact, with excessive stocking rates causing soil compaction, erosion, vegetation change, and reduced carrying capacity for native wildlife. Mining operations, particularly for copper, lithium, gold, and other minerals, create severe localized impacts, including habitat destruction, water depletion, and pollution. Agricultural expansion in irrigated valleys converts natural habitats and alters hydrological regimes. Urban growth, particularly near major cities such as Mendoza, Santiago, and Antofagasta, fragments habitats and generates pollution.

Climate change presents emerging challenges, with projections suggesting increased temperatures, altered precipitation patterns potentially including reduced rainfall in already water-limited systems, and more frequent extreme weather events. Species with narrow environmental tolerances or limited ranges, particularly endemic taxa confined to small areas within the diagonal, face heightened extinction risks.

Despite these challenges, conservation opportunities exist. Protected areas, including Los Cardones National Park in Argentina, Pan de Azúcar National Park in Chile, and Paracas National Reserve in Peru, provide refugia for native species. However, the protected area network remains incomplete, with many ecoregions and concentrations of endemic species inadequately represented. The expansion and improved management of protected areas are priorities.

Community-based conservation initiatives that provide economic alternatives to destructive practices show promise. Ecotourism, when properly managed, can support local economies while incentivizing conservation. Sustainable livestock management practices can reduce grazing impacts. Recognition of Indigenous territorial rights and incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge into management planning can enhance conservation effectiveness while supporting local communities.